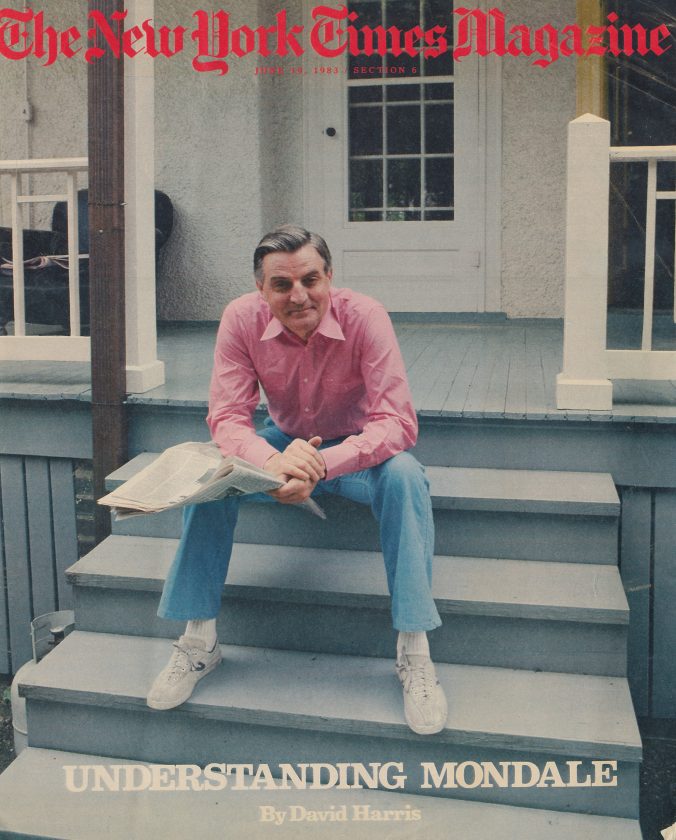

New York Times Magazine – June 19, 1983

The place is Jackson, Mississippi, and former Vice President Walter F. Mondale is here to deliver a speech from the front steps of the Mississippi Governor’s mansion. His performance is not unlike those he has given in 100 cities in 26 states between January and June of this year. A sprinkling of national press has come along to watch, and Mondale exhibits guarded ease. He is 55 years old and has no illusions about the process he must go through to win the Presidency. The reporters have come to examine his soft spots, and neither he nor they need to be told that the last two decades of Democratic Party history have been littered with the mistake-plagued wreckage of early front-runners.

On the other hand, not making mistakes is one of Walter Mondale’s strong suits.

Aside from the mistakes he does not make, his speech in Jackson is most notable for all the things Walter Mondale does not say about himself. It is typically well-delivered and just as typically unrevealing. He laments the collapse of the farm economy, but tells no stories about his father, the farming prairie preacher who lost everything in the 1920 farm-price collapse. He warns about the escalation of health-care costs for the elderly, but reveals nothing about how his mother’s insurance company dropped her coverage when her cancer was discovered and how her three sons bore the costs of her prolonged treatment. As he stands on the front porch of the mansion, his profile is dominated by the almost right angle his nose makes after emerging from his face, but few people in this football playing state will learn that the shape of his nose is a scar from the constant breakage it endured during his career as “Crazylegs” Mondale, the shifty iron-man halfback of the Elmore, Minnesota, high school varsity.

Walter Mondale is ashamed of none of those things, but he nonetheless does not bring them up on his own. He resists packaging his person, despite the potential political benefits, and his performance in Jackson reveals no sudden breaks in that resistance.

Mississippi is a state dominated by small towns, but Mondale gives only several phrases in passing to having grown up in Ceylon, Heron Lake and Elmore, Minnesota, the largest of which had a population of 950. It strikes no one watching him that he is reportedly a direct descendant of a seventh-century Viking warlord. He mentions he is a “minister’s kid,” but does not mention, as he does in private, that “being a minister’s kid was a free ticket for everyone to beat you up.” Nor is there any indication that he was the kind of minister’s kid who once organized his playmates to build a bridge using hymnals purloined from his father’s church and is still possessed of a broad, if private, streak of mischief. And his manner does not suggest the kind of politician who once disguised himself as a farm worker to investigate conditions among migrant laborers.

All those parts of Walter Mondale are a vacuum in his public presence. He offers few clues to the facts that as a teen-ager he sang at weddings and sold vegetables door to door during the Great Depression. He promises the crowd in Jackson that if he is elected President, everyone’s children will have the possibility of a college education, but makes no mention of the heavy debt he assumed as a young man putting himself through college. That he is intelligent is ap parent, but that he rereads the works of William Shakespeare every few years is not apparent at all.

He extols the virtues of family life and calls families “the basis of a strong nation,” but even with his wife, Joan,. standing behind him on the Mississippi mansion porch and smiling, he does not personalize the issue. That they mean a lot to each other and have been married 27 years remains unsaid. That their three children are a former dirt-bike racer, an aspiring actress and an undergraduate fluent enough in Spanish to translate on Vice-Presidential missions, all goes unsaid as well. Choosing between their privacy and his image, Mondale has always chosen their privacy. Joan does their family grocery shopping through a neighborhood buying club and takes a regular trip to the Washington farmers market as part of the Mondales’ membership, but consumers struggling with food prices will not learn that information. from Walter Mondale.

This is an election in which Democrats will belabor “the rich,” but Mondale does not point out that his own net personal worth when he left the Vice Presidency was a meager and palpably uncompromised $15,000. Similarly, he uses the words “strong” or “strengthen” 17 times in 12 minutes but offers no descriptions of how, as a stand-in head of state, he faced down President Ferdinand E. Marcos in the Philippines, wrangled with Prime Minister John Vorster over South Africa, or softened up Prime Minister Menachem Begin at Camp David. He instinctively shies away from any talk that might sound too much like bragging on himself.

When Mondale finishes his speech in Jackson, the audience is impressed and the national press contingent agrees that he deserves his growing reputation as the best speechmaker of the Democratic pack, but his oratory, though enormously improved, is still a far cry from charisma. Few of the issues he addresses attach to his person. In image-maker’s terms, he lacks “projection.”

The modern Presidency is won with visceral characterizations and personified emotions, yet the absence of such images and associations from the presence of Walter Mondale is striking. There is indeed a person behind his candidacy, but Mondale resists revealing himself. That tendency in turn frames the ground where Walter Mondale’s political and personal dilemmas overlap. By his own choice, he is at the same time a formidable enough commodity to be considered a political fixture, yet as a person so unknown as to be effectively indistinguishable from his circumstances.

The modern Presidency is won with visceral characterizations and personified emotions, yet the absence of such images and associations from the presence of Walter Mondale is striking. There is indeed a person behind his candidacy, but Mondale resists revealing himself. That tendency in turn frames the ground where Walter Mondale’s political and personal dilemmas overlap. By his own choice, he is at the same time a formidable enough commodity to be considered a political fixture, yet as a person so unknown as to be effectively indistinguishable from his circumstances.

At this writing, Walter Mondale leads the Democratic Presidential race in national polls, money raised and straw votes won. His campaign organization and strategy are commonly thought the most professional in the six-man field (see The Strategy: Getting off to a fast start below). His closest competitor, Senator John H.Glenn of Ohio, the former astronaut, is considered to be a serious threat to win the prize of the party’s nomination.

Not surprisingly, then, the first question asked about Walter Mondale : is whether he is really as boring as his coverage makes him seem.

The only answer is a character portrait that is much more complex than the stereotype “boring” implies.

Walter Mondale, to start with, is Norwegian. According to those around him, his often overlooked ethnicity is central to who he is and how he presents himself. Mondale is the Anglicization of Mundal, the village on the shores of Sogne Fjord where his great-grandfather lived before immigrating to southern Minnesota in 1856. The winters are desolate and lonely in Ceylon, Heron Lake and Elmore, and the broad prairie around them was consequently settled by a patchwork of Swedes, Danes and Norwegians whose culture is still among the nation’s most distinct, if least visible, ethnic enclaves. Its orthodoxy is politically liberal and personally conservative, though “conservative” does not capture the scope of the Scandinavian emphasis on privacy, self discipline and emotional containment. “There is a restraint against feeling in general,” one Minnesota writer observes. “There is a restraint against enthusiasm . . . there is restraint in grief, and always, always re straint in showing your feelings.” The Minnesota subculture that nurtured Walter Mondale is very likely the most intense outpost of personal reticence left in modern America.

Mondale smiles as his press secretary, Maxine Isaacs, tells an illustrative Norwegian story. They, several staff people and two reporters are flying in a chartered eight seater to the Quad Cities Airport after a 7:30 speech in Dubuque, Iowa, on Jan. 28. The story is about a Minnesota reception Vice President Mondale appeared at during the 1978 Congressional campaign in one of the farm towns out on the prairie. Twenty people attended. When Mondale entered, the crowd issued several claps and then everyone stood where they were while Mondale patiently approached each and initiated conversation. No one approached him on their own or gave his inquiries more than a one sentence answer. Meanwhile, the local Norwegian organizer of the event, obviously thrilled by the crowd response, approached Mondale’s press secretary. “Quite a fanfare, isn’t it?” he exulted in all seriousness. Mondale breaks into chuckles at the punch line.

Though by this point in his life Walter Mondale has evolved into a positively flashy figure by the standards of his native subculture, its expectations of reserve are ingrained in his personality.

During the question period at the Land o’Lakes Co-op’s annual meeting in the Minneapolis Civic Auditorium, Mondale is asked if he thinks he would be a good President. “I have trouble answering that,” he confesses. “If my father had ever heard me tell him that I would make a good President, I would have been taken directly to the woodshed.” The audience laughs, knowing exactly what he means.

“The whole idea of talking in terms of me or I is foreign to the culture,”

Mondale explains. It is March 26 and he is riding in a rented car, traveling from Portsmouth, N.H., to the Boston airport. There, he will start a series of filghts that will land him in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for a 3 P.M. press conference. “Talking in terms of me or I just wasn’t done,” he continues. “In my family, the two things you were sure to get spanked for were lying or bragging about yourself. Both were equally unacceptable.” He and a reporter are sharing the back seat and Mondale answers most questions while staring ahead at the road. “Now, of course,” he offers, looking the reporter in the face, “I have to talk about myself and I do.” The answer is, not surprisingly, less than revelatory. According to his staff, Mondale still assumes, in an instinctively Norwegian way, that personal promotion is demeaning and that who he is will be apparent without being hyped. Both assumptions may prove crucial in an election that could be decided on television.

The second thread in Walter Mondale that parallels his stereotype is his caution. It is a Norwegian character trait that has been buttressed by the unique mechanics of his 23 years in public life. Attorney General of Minnesota, United States Senator, Vice President, Mondale’s career is extraordinary for the fact that he has never officially entered any political contest in which he was not either the front-runner or the incumbent. That unusual experience has entrenched his caution, and the most formative step in the process was the first. In 1960, when he was l2 years old, less than five years out of law school, and already an experienced Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party operative, he was appointed by Gov. Orville Freeman to fill the state Attorney General’s office vacated by resignation. Out of nowhere, Mondale held the second most powerful elective office in the state. His predecessor, Miles Lord, had been something of a controversial showboat, but Mondale went in the opposite direction.

The second thread in Walter Mondale that parallels his stereotype is his caution. It is a Norwegian character trait that has been buttressed by the unique mechanics of his 23 years in public life. Attorney General of Minnesota, United States Senator, Vice President, Mondale’s career is extraordinary for the fact that he has never officially entered any political contest in which he was not either the front-runner or the incumbent. That unusual experience has entrenched his caution, and the most formative step in the process was the first. In 1960, when he was l2 years old, less than five years out of law school, and already an experienced Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party operative, he was appointed by Gov. Orville Freeman to fill the state Attorney General’s office vacated by resignation. Out of nowhere, Mondale held the second most powerful elective office in the state. His predecessor, Miles Lord, had been something of a controversial showboat, but Mondale went in the opposite direction.

“I am young and start with no base at all,” he told a friend. He knew his best option was to play his role extremely close to the vest. “I’m not even going to smile,” he explained. And he didn’t. He also never allowed himself to be photographed with a drink in his hand or be seen talking to an “unattached woman.” He went to work early and stayed late. Later in 1960, he comfortably won “re-election.”

Mondale’s caution bred a style that is inoffensive, deferential and thorough, and those virtues in turn made Walter Mondale a very successful, if relatively colorless, politician. In 1964, Gov. Karl Rolvaag of Minnesota appointed him to the Senate seat vacated by Hubert H. Humphrey upon his election to Vice President, and Mondale won election on his own in 1966 and 1972. In 1976, Jimmy Carter elevated Mondale to the Vice Presidency. “The thing that is most evident about Mondale,” Humphrey once explained, “is that he”s non-abrasive. He was not a polarizer. He coupled all this with what was obvious talent: He was young, he was articulate, he was intelligent, and clean-cut. He kept filling the bill. It’s most amazing.” A less cautious man might not have been so acceptable to all concerned and Mondale has made remarkably few enemies in 20 years of holding offices.

Thus far, Walter Mondale seems most cautious about the issue of Jimmy Carter. Carter’s 1980 defeat is a disaster Mondale must distance himself from, yet he must do so without seeming to be disloyal or denying his own history. Indeed, Mondale wants his Vice Presidency remembered as much as he wants Jimmy carter forgotten. It is a tricky balancing act. Questions about Mondale’s attitude toward his former boss come up everywhere. At Mondale’s March 7 press conference in Jackson, he gives his standard answer. He has recently been chided in several national columns for his remarks in an interview published under the headline “Mondale, no more a loyal defender, trying to establish his independence,” and though Mondale considers the chiding unfair, he knows better than to whine to the press about the coverage he’s getting. “I was proud to serve as Mr. Carter’s Vice President,” he says instead. “There was much that we did that’s going to look very good in American history. We had some problems, we had some bad breaks. That’s the way it is. Now I’m running for President.”

The answer is one reporters call “surefooted.” Mondale’s caution is, of course, political wisdom when the issue is how to avoid giving offense, but when the issue is “boring,” it works against him. He provokes little heat either pro or con and consequently makes bland copy. It is one of the reasons analysts describe his support in the polls as “shallow.” Having always run from the passive posture of either defending an office or defending a lead, he has never had to seize the public imagination and run with it, as most challengers must. Whether he can or not is, after 23 years, still an open question.

The final element in the character behind Walter Mondale’s stereotype is his inwardness. Though now one of the most charming elbow-rubbers and handshakers in the Democratic Party, when he first took the Minnesota attorney generalship he entered his office every day by a private door to avoid having to make small talk with the secretarial help. He is a private person and not instinctively convivial. He can entertain himself by staring out a window and is most at ease with just himself in the room. Though he talks little about his own psychology, Mondale admits that he has ritualized his need to drop everything and look inward in the form of regular fishing trips and that they are central to his inner workings. At an Iowa City Foreign Relations Council meeting he jokes about them. “I was once asked why I fished,” he says, “and I said it was cheaper than a psychiatrist.”

For the last 25 years, Mondale’s partner in this emotional therapy has been Fran Befera, a Duluth television station owner. The two men angle for trout and wall-eyed pike in the Minnesota lakes reachable only by seaplane. In winter, they chop holes in the ice and do the same thing. Often Befera’s sons come along and the trips usually last five or six days. They stay in Befera’s fishing shack, take along canned tuna in case nothing is biting, and what talking they do is just “camp talk.” No issues, no campaigns, no public-opinion polls. Just understated male phrases about fish, the weather, and more fish. Most of the time, Mondale sits with his line in the water and says nothing. “Your system is driven by the sport to calm down,” he explains. “That’s what it’s all about. After about the fourth day, I start to get my perspective back – the little irritations and anxieties disappear. I can think about the big picture again.”

For the last 25 years, Mondale’s partner in this emotional therapy has been Fran Befera, a Duluth television station owner. The two men angle for trout and wall-eyed pike in the Minnesota lakes reachable only by seaplane. In winter, they chop holes in the ice and do the same thing. Often Befera’s sons come along and the trips usually last five or six days. They stay in Befera’s fishing shack, take along canned tuna in case nothing is biting, and what talking they do is just “camp talk.” No issues, no campaigns, no public-opinion polls. Just understated male phrases about fish, the weather, and more fish. Most of the time, Mondale sits with his line in the water and says nothing. “Your system is driven by the sport to calm down,” he explains. “That’s what it’s all about. After about the fourth day, I start to get my perspective back – the little irritations and anxieties disappear. I can think about the big picture again.”

He finds sustenance and focus in being nobody with nothing much to say and his therapy amounts to long, silent hours adrift, watching how the light lifts off the water and the ripples scatter toward the shore. Where others might be bored, Walter Mondale is rejuvenated.

But on the campaign trail, being interviewed in the back seat of his rented car, Mondale differs strongly with all the attention paid to his stereotype. “Maybe I am boring,” he says, “I don’t know. I read about it but I don’t think my audiences are bored. You’ve seen them; are they bored?” The reporter allows that most of the people who come out to see Mondale seem to enjoy what he has to say. “Sure,” Mondale continues, “I lay an egg once in a while just like anyone. But I think there’s pack journalism operating here, too. If one of the bureaus writes a story that I’m boring, then all the rest do. What’s really interesting is that for 18 months I was on the road and none of the national press was there, but they were all writing stories about how boring I was. It always fascinated me how they knew.”

Deserved or not, Mondale’s stereotype has obscured some attractive attributes:

He is bright and, by politicians’ standards, enormously literate. A friend, the historian Barbara Tuchman, supplies him with reading lists, and his favorite book is George Trevelyan’s biography of Garibaldi. For fun, he hunts quotations in the Shakespeare concordance Joan gave him for Christmas. On the few occasions when he watches television, he sticks to old movies. His home life with Joan has an updated Ozzie and Harriet flavor. The Mondales live on Lowell Street in northwest Washington and, on his occasional days off, Mondale can be seen in chino pants, jogging shoes and an old purple letterman’s jacket walking Digger, his daughter’s dog, in Cleveland Park.

Joan campaigns, does volunteer work for the arts and makes pots in her, pottery studio. Mondale likes sit up in the evenings and read. He is the son of a Methodist minister, she is the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, and today they are Presbyterians who don’t get to church very often. He plays tennis and takes medication for what he describes as a “managed, controlled, modest” blood-pressure condition. Joan calls him Fritz and he calls her Joan. Mondale’s staff calls him Mondale or sir. He obliges everyone who recognizes him in airport lounges with conversations and says he enjoys doing so. Most of them call him Mr. Vice President or Mr. Mondale. He drinks one light scotch and water a day and chews three or four long, thick cigars. The cigars disgust Joan and she jokingly gripes about having to empty his ashtrays.

At home, they eat their dinners at the dining-room table and, following her lead, circulate on the culture circuit. They rarely entertain these days, but when they do it is mostly with Senators and their wives, some of whom live in the neighborhood. Since the Vice Presidency, he has earned a “six-figure” income as a Washington lawyer with Winston & Strawn, but the only signs of his new wealth are the car and driver provided by the campaign and the recently purchased home in Minnesota where the Mondales plan to retire someday. “Decent” and “unpretentious” are two words all Mondale’s friends use to describe him.

The most visible of Mondale’s personal attributes is his sense of humor.

On the evening of Jan. 28, he is speaking to a gathering of 125 Iowa Democrats in the Fleur de Lis room of Dubuque’s Julien Motor Inn. The room’s glitter ceiling is lit with orange and yellow lights. Dubuque County has the second heaviest concentration of Democrats in the state, and doing well here is a key to carrying the caucuses next February. Ten minutes into his performance, he delivers one of the set jokes he salts throughout his standard Iowa stump speech. “This is a country where everybody can run for office,” Mondale observes in his driest twang, “and, as you know, in the Democratic Party. everybody does.” The audience laughs. “Usually for President,” Mondale adds. The audience laughs even harder.

Weeks later, he is at the solar-heated headquarters of the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests in Concord. Senator Gary Hart of Colorado, a rival for the nomination, has been here the week before, drawing an audience of 50. Mondale draws 85. In the question-and-answer period, Mondale makes a point about “the pursuit of happiness” as a national goal, using an off-the cuff one-liner. “Did you ever see a picture of the Politburo?” he asks rhetorically. “They all look like morticians who weren’t paid for the last funeral.”

At a Washington convention of the United Automobile Workers political arm, the Community Action Program, Mondale is one of the featured speakers. He is brought in to a standing ovation and introduced with effusive praise. The banner behind him reads: “Forging Coalitions to Advance Workers Goals.” Mondale opens by recognizing most of the union’s officers individually and then comes out with one of the standard lines he uses to josh his political friends. “I know how these U .A. W. conventions work,” Mondale begins, tongue-in-cheek. “You figure out who you’d really like to hear and then, when he turns you down, you ask old Walter Mondale if he has a new speech yet.”

If he holds the lead, Walter Mondale will be the most quick-witted Democrat to head the ticket since John F. Kennedy. He will also be the most politically experienced since Lyndon B. Johnson. Walter Mondale held high public offices for 20 continuous years from 1960 to 1980. The 12 years spent in the Senate have left him completely familiar with the legislative process. His four as Vice President are generally agreed to have included more direct and influential involvement in the daily workings of the executive branch than any Vice President in history. The breadth of his experience is one point Mondale makes about himself with no reticence at all.

On the evening of March 7, Walter Mondale’s tour of three southern states has reached Chattanooga, Tenn., where he addresses a reception sponsored by Chattanoogans for Mondale in the Sheraton Downtown Hotel. Some 250 Democrats attend, making heavy use of the cash bar. It is one of those audiences Mondale describes as “raw meat,” and he works them determinedly. His face flushes and, as the words come out more and more rapidly, they shape themselves into a rhythmic cadence. The register of his voice rises and becomes increasingly nasal. “I am running for President,” he declares. “I’m going to give it all I’ve got. I know state government, I know the Senate, I know the White House, I know the world. I know what I’m doing. And that’s the final point: We need a President who knows what he’s doing!”

The Chattanoogans applaud boisterously and sweat trickles down the side of Walter Mondale’s face.

The Chattanoogans applaud boisterously and sweat trickles down the side of Walter Mondale’s face.

When he is lathering up a crowd like the one in Chattanooga, Mondale sounds a lot like Humphrey, and the resemblance is no accident. Mondale refers to the late Senator from Minnesota often, usually as “my old friend, Hubert” or “my mentor, Hubert Humphrey,” a “source of public inspiration and a deep, deep friend.” Their relationship began as college student to United States Senator, became aspiring politician to established power, and then, when Mondale came to the Senate and Humphrey assumed the Vice Presidency, junior public official to senior. It was while Humphrey was Vice President that Mondale, at least partly out of loyalty to his mentor, supported Johnson’s Vietnam policy, a stance he now calls “the worst mistake of my public life.” When Humphrey left office in January 1969, Mondale came out against the war.

Despite their long association, it was not until 1971, when Humphrey returned to Washington as the junior Minnesota Senator to Mondale’s senior, that what one of Humphrey’s aides would later call “a special communication” developed between the two men. As Humphrey’s health ebbed, he increasingly saw Mondale as the political heir who might succeed in attaining the Presidency where Humphrey himself had failed. According to Mondale, by 1978, when Humphrey lay in the hospital dying, their friendship “had blossomed into something very, very deep.” The last time the two men saw each other, Humphrey talked at length about how much Mondale’s career meant to him. “Keep it up,” Humphrey said. A friend of both men described Mondale as “anguished” over Humphrey’s death.

Ironically, it was Humphrey who first raised the doubts about Walter Mondale’s staying power that have plagued Mondale’s Presidential aspirations for the last 10 years. In a newspaper interview in 1973, Humphrey wondered pointedly whether Mondale had “the fire in the belly” it takes to become President. The question has been asked about Mondale ever since. Humphrey’s remark was made in the course of the still-born 1974 exception to Mondale’s pattern of front-running a sequence remembered now as “the last time Walter Mondale ran for President.” Humphrey set the process in motion on election night in November 1972. Mondale had just easily carried his second Senate re-election in the face of a Republican sweep, and Humphrey, ebullient, dragged him in front of the national television cameras and proclaimed him Presidential material. When Mondale was slow to take advantage of the opening, Humphery uttered his “fire in the belly” remark. In January 1974, Mondale finally announced that he was “actively exploring the possibility of running” and spent the next year on the Democratic rubber-chicken hustings. At the end of that year, Mondale stood at 3 percent in the polls. “I was two points behind Don’t Know and wanted to challenge him to a debate, ” he now jokes, “but Don’t Know wouldn’t debate me.” In November 1974, Mondale called Humphrey. “Humphrey,” he said, “I’m getting out of this thing.”

On Nov. 21, 1974, Mondale announced that he would not be a candidate for President in 1976. Until he called his press conference, both Joan and his staff expected he would run. Instead, Mondale joked to the press that he didn’t want to spend the rest of his life in Holiday Inns, and then issued a brutal assessment of himself. “I do not have the overwhelming desire to be President which is essential for the kind of campaign that is required,” he announced. “I admire those with the determination to do what is required to seek the Presidency but I have found that I am not among them. “

Now, eight and a half years later, Mondale is talking about 1974 on his way to the Boston airport. He has spent the previous night in the Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Holiday Inn, the latest of dozens of such Holiday Inns he has stayed in since 1974. By now, Mondale is used to being asked if he is sufficiently driven to be President. He is chewing on a cigar when the subject comes up. “In 1974,” Mondale explains, “I tried to run on a part-time basis for a year and it became obvious that you have to run full time. I was a Senator, I loved being one, and I didn’t want to give up being one. Deep down, I wasn’t ready and I knew it. The more I thought about it, the more I asked myself, ‘O.K. Mondale, what do you really want to do? What is it that you think makes all of this so important to the country?’ I couldn’t answer it. Now, with the experience of the White House, without the conflict of two jobs, I feel ready. I’m convinced I can run that Government. I’ve got a clear vision. I believe I can be a very good President.”

When he finishes, the cigar is out of Walter Mondale’s mouth and he is looking off toward the countryside. The persistence of doubts about Mondale’s drivenness is, among other things, a reflection of how little he is truly known. His considerable political skills are, to a great extent, the result of the diligent long-term exercise of his will to improve and he has, through determined effort, elevated himself from running behind Don’t Know in 1974 to running ahead of everybody in 1983. (At this writing, Gallup and Harris polls of Democrats show him ahead of the other candidates for the nomination.) Both developments bespeak the activity of someone who wants something very much. His schedule looks driven as well. In the 1982 elections, Mondale campaigned on behalf of 95 House, 15 Senate and 18 gubernatorial candidates. Thus far in 1983, he has been on the road three weeks out of every four, working 12-and 18-hour days. He exhibits little ambivalence about his task. Perhaps the more relevant question is not whether Walter Mondale is driven, but what is doing the driving. As one of his aides has pointed out, he is not “the kind of guy who wakes up in the morning with ‘Hail to the Chief’ ringing in his ears.”

The human being most responsible for the shape and intensity of Mondale’s motivation was his father, Theodore. If will were a matter of genetic inheritance, there would be no question about Walter Mondale’s.

The human being most responsible for the shape and intensity of Mondale’s motivation was his father, Theodore. If will were a matter of genetic inheritance, there would be no question about Walter Mondale’s.

Theodore, a stutterer, made himself into a preacher with a six-month course at Minnesota’s Red Wing Seminary. After contracting lockjaw in a kitchen-table tonsillectomy during the early 1920’s, Theodore regained the full use of his mouth by spending a year jamming a piece of wood between his jaws and slowly prying them open. He was 52 years old when his son Walter was born. Theodore had lost the last of his farms by then and the Mondales were living on the meager proceeds of rural Minnesota ministerial postings in the likes of Jeffers, St. James, Ceylon, Heron Lake and Elmore. Walter was the second son of Theodore Mondale’s second family. Theodore’s first wife had died after 18 years of marriage and their children were grown when he married Walter’s mother, Claribel Cowan. (There are six children altogether from the two marriages.) Claribel gave music lessons and led the choir in each of Theodore’s succeeding parishes. She and Walter were close, but, by all accounts, the dominant presence in Walter Mondale’s childhood was his father, the minister.

“Being a minister’s child is similar to being a public official’s child,” Joan Mondale explains. She is sitting in the Mondales’ living room on Lowell Street. The house has two stories and is tastefully decorated. The neighborhood outside is leafy and upper-middle-class. Her husband, home for five days after several weeks of travel, is walking the dog. She is winding up the interview before rushing to a hairdresser’s appointment. “As a minister’s child,” she continues, “what you say and do will be remembered. You have to be careful. What you say will be repeated. You aren’t necessarily welcome when you move into a community. You have to think again about what you say and you have to prove yourself – prove that you’re one of the gang – over and over. Fritz grew up with that.”

The minister’s son must prove himself to his father “over and over” as well. Theodore Mondale was a no no-nonsense disciplinarian who administered the switch to Walter on more than one occasion, but they were deeply bonded. Theodore had high standards and young Walter apparently lived up to them. He was a passable student, a school leader and a local athletic hero. Theodore Mondale’s passion was politics and Minnesota’s home-grown Farmer-Labor party and this, too, he inculcated in Walter. “Dad was basically the politician of the family,” Mondale explains. “He was a devout Christian, a believer in the social gospel, a Farmer-Laborite. He believed Christ taught a sense of social mission and this was heavily given to me throughout my childhood. He came out of the progressive Scandinavian tradition. We always discussed politics. My dad stuttered and wasn’t a man of letters, never really more than a farm kid all his life. Often, I’d hear people ridicule him. He wasn’t as smooth as he was supposed to be, I guess. But he had a lot to do with me going into political life. I wanted to fight for the things my father believed in.”

The Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party Theodore Mondale taught his son to admire was a powerful force in the early 1930’s but then waned until merging with Minnesota’s Democratic Party into the modem D.F.L. in 1944. A number of future national politicians rose out of that merger, all of them led by Hubert Humphrey, the exciting young Mayor of Minneapolis. When Walter Mondale, 20 years old and a Macalester College undergraduate, enlisted in the ranks of Humphrey’s 1948 Senate campaign, it was the kind of thing he had been raised to do. Reportedly, Mondale’s proudest moment of that campaign was when he introduced Humphrey to his 72-year-old father. Theodore Mondale’s approval continued to mean a lot to Walter, and Theodore approved of Humphrey enormously. Theodore died six weeks after Humphrey won his 1948 Senate election. To this day, his father’s expectations seem to be strung quite tightly inside Walter Mondale. He remains, at his core, a minister’s kid who, having proved himself again and again, still has something left to prove.

“Proof” this early in the campaign has centered on joint appearances by all the candidates that Mondale calls the Democratic Party Traveling Gong Show. The first was in California in January. Each candidate addressed a party convention and Mondale drew raves from press and delegates as “the most impressive.” The second was in Massachusetts in February, and Mondale received the most enthusiastic reception.

On March 8, the Democratic Party Gong Show comes to Atlanta’s World Congress Center to play in front of the Georgia state party’s Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner. Twenty five hundred Democrats from all over Georgia attend in black ties and evening gowns. The music is provided by Dean Hudson and his orchestra. Dancing is planned for after the speeches. Dinner costs $150 a person and the party will net a quarter of a million dollars. There is a dais, but no head table, just enough individual 12-seat arrangements to cover the floor of a cavernous convention center decorated to resemble an up scale dinner club. Dozens of reporters and cameramen mill around near the podium and at the bar. Bert Lance, former Carter Administration Director of the Office of Management and Budget, who was forced to resign and now is the state party chairman, is the evening’s master of ceremonies.

Lance solves the only backstage controversy of the evening by arranging a group photo when all the candidates come to the dais. Mondale missed the group photo in California “for scheduling reasons” and did the same thing for the same reason in Massachusetts. Some national press photographers wonder if Mondale is ducking, and his press secretary has been assuring them all week that he will pose. He does. smiling. Afterward, the candidates go at it in alphabetical order. In California and Massachusetts, Mondale spoke first for “scheduling reasons.” Tonight, he speaks last. As each speaker is at the rostrum, the rest sit behind a long table. All of them stare into a spotlight whose glare obscures everything but the first row of press photographers two feet away.

Reubin 0. Askew of Florida has a gray suit and a nervous tick in his right eyelid. Senator Dale Bumpers of Arkansas also wears gray and will be out of the race in less than a month. Alan Cranston of California has sent his son as a stand-in, effectively ceding the evening but paying his respects. Senator Glenn tells a Walter Mondale joke: “Fritz Mondale spent the week listing his differences with the President,” says Glenn, pausing for effect. “Fortunately, President Carter didn’t take it personally.” The line draws laughs, Glenn is applauded, but the applauders stay in their seats. Next, Senator Hart proclaims himself the dark horse in a relatively dark and wooden way, and then Senator Ernest F. Hollings of South Carolina drawls through the longest speech of the night. Mondale listens with alternating airs of indifference, bemusement and distraction. He doesn’t seem nervous, yet it is apparent that he is just waiting his turn.

When he reaches the podium, last in line, Mondale starts slowly. He mentions all the party notables present, tells a funny story about “old Hubert,” and reminds the audience that Walter Mondale “helped elect the first Southern President in 120 years.” Mondale does not, however, mention Jimmy Carter by name and will be the only one of the candidates not to do so. Mondale next talks about how the values at one end of the Mississippi River are the same as at the other. “I learned to believe in God, to obey the law, to tell the truth, work hard, and to do my duty,” he says. From that point on, Mondale steadily quickens the tempo. He is the only candidate who senses the raw meat in the audience and plays to it. They want stimulation, and his voice rises and the words pile out in bursts. He evokes “the values of the family” and Democrats as “the party of caring.” It is a performance one of the more cynical of the reporters present describes as “Walter Mondale sings Hubert Humphrey’s Greatest Hits.” For the last two minutes, Mondale’s chest is thrust against the podium, while he speaks in a half shout and thumps the air with his arms.

When he reaches the podium, last in line, Mondale starts slowly. He mentions all the party notables present, tells a funny story about “old Hubert,” and reminds the audience that Walter Mondale “helped elect the first Southern President in 120 years.” Mondale does not, however, mention Jimmy Carter by name and will be the only one of the candidates not to do so. Mondale next talks about how the values at one end of the Mississippi River are the same as at the other. “I learned to believe in God, to obey the law, to tell the truth, work hard, and to do my duty,” he says. From that point on, Mondale steadily quickens the tempo. He is the only candidate who senses the raw meat in the audience and plays to it. They want stimulation, and his voice rises and the words pile out in bursts. He evokes “the values of the family” and Democrats as “the party of caring.” It is a performance one of the more cynical of the reporters present describes as “Walter Mondale sings Hubert Humphrey’s Greatest Hits.” For the last two minutes, Mondale’s chest is thrust against the podium, while he speaks in a half shout and thumps the air with his arms.

The Georgians love it and give him a standing ovation. He receives the applause with an abashed smile. He is genuinely thrilled that all those people could be clapping for him.

Mondale leaves the World Congress Center through a backstage entrance accompanied by Joan, several staff members, and several national reporters.

“Hell,” one of the reporters joshes Mondale, “if you’re gonna be that good, they’ll make you talk last every time.”

There is only the faint hint of a chuckle in Mondale’s voice as he answers. “That was somethin’, wasn’t it,” he exclaims.

All candidates must contend against not only their opponents but also themselves. In this second race, matched against his own limitations, Walter Mondale has yet to stamp his identity firmly on the lead he holds, and doing so is essential. He must also answer at least two significant outstanding doubts about himself.

The first is whether he can come across on television. “I’m not good on,” TV,” Mondale admits. “It’s just not a natural medium for me.” Part of the reason is pure cosmetics. A reasonably trim man, Mondale’s face invariably looks heavier than the rest of him and television cameras seem to heighten that jowliness. His eyes are dark blue and set in deep, permanently smudged sockets. In the esthetics of television, the lack of contrast translates into two distant dead spots in the middle of his face. The way his voice rises and goes nasal when making a point is a drawback as well. More central to his video difficulties, however, is Walter Mondale’s own uneasiness with the medium. He is uncomfortable assuming the star quality it demands and has difficulty with the idea of presenting himself unselfconsciously to a box with lights on it. He has thus far resisted advice to seek coaching. Mondale for President will soon hire the Austin, Texas, advertising firm of 33-year-old Roy Spence to handle its media. Spence did similar work for Gov. Mark White’s election in Texas but is a newcomer to national campaigns. He will have his hands full.

The second doubt about Walter Mondale is whether he can keep from being perceived as no more than the prisoner of his friends. Mondale was the only Presidential candidate invited to the retirement dinner given by the United Automobile Workers for their president, Douglas A. Fraser, in Detroit’s Cobo Arena. Autograph hunters swarmed around Mondale’s place at the head table. “Fritz fits into our plans,” an officer of Lansing’s Local 652 explains. “He’s a President of the people. It’s people programs that make us go.” Mondale receives a standing ovation when he is introduced to speak. “I want to thank you for making me feel at home,” he says. At the end of the program, Mondale stands and joins hands with the rest of those at the head table in singing “Solidarity Forever.”

On Jan. 30, Mondale is the featured speaker at a black-tie fund-raiser for the United Jewish Appeal at the exclusive Jimmy’s Restaurant in Beverly Hills, Calif. More than $5 million will be raised from the 60 couples on the guest list, half designated for local projects, half for projects in the state of Israel. Mondale is introduced as someone who “shares completely the commitments that bring us together tonight.” In the course of Mondale’s speech, the return of territory by Israel as part of the Camp David agreements is likened to “an American President coming back and saying ‘I got peace with the Russians and all I had to give up was everything west of the Mississippi.’ “

A month later. Mondale meets with a group of 35 farmers in the Hawkinsville, Georgia, public library in rural Pulaski County. The farmers have all been brought together by a local banker and all of them are deep in debt. “I will be the best pro-farm President America has ever had,” Mondale promises.

On March 25, Mondale stops at Boston’s Harriet Tubman House, a Federally funded community center, and meets with a dozen activists from the Hispanic community. Mondale takes his coat off and speaks with his hands on his hips. “I would appoint Hispanic-Americans to positions of real power,” he declares flatly. “I want to be the President who breaks the ice for Hispanic-Americans.”

Mondale’s strategy is both orthodox and risky. He intends, quite simply, to reunite the fractious Democratic coalition by running as the candidate of each of its separate pieces, all at the same time.

The issues he emphasizes are appropriately “mainstream” in the spectrum of Democratic Party activists. Hart and Cranston are perceived as slightly to Mondale’s left, Askew, Glenn and Hollings to his right. Mondale regularly opens his stump litany with unemployment, a condition he blames on high interest rates, weak trade policies and the Reagan Administration’s enormous deficits. He also regularly attacks the imbalance of America’s international trade posture, the threat of nuclear war, the “mishandling” of Central America, acid rain, James Watt, and the disintegration of the quality of American education. To deal with these national problems, he supports “domestic content” legislation as a necessary sign of “toughness” in our trade posture and proposes a series of international negotiations to establish trade “reciprocity.” He also calls for new international monetary agreements in which the net result will be the devaluation of the American dollar, thereby making American exports more competitive and foreign imports less so. He has promised to repeal the scheduled tax cuts for people with incomes over $60,000 a year, to repeal income-tax indexing and “put a lid on hospital costs.” He has endorsed a “verifiable nuclear freeze” and advocates “scaling the defense budget to reality. ” In the Middle East, he is pledged to continuing “the Camp David process,” and in Central America he has proposed hemispherewide negotiations to stabilize the region. In response to the recent highly critical report of the National Commission on Excellence in Education, Mondale has proposed a new program of $11 Billion in Federal aid to local school districts. He also supports even tougher enforcement of the Voting Rights and Environmental Protection Acts.

The first risk in Mondale’s “mainstream strategy” is that not all the pieces of the Democratic puzzle get along easily with one another and the possibility of getting caught in a political cross fire is large. The second risk is that pleasing all of those constituencies sufficiently to win the Democratic nomination might well leave Mondale looking overpromised when the electoral base widens in the general election.

The first risk in Mondale’s “mainstream strategy” is that not all the pieces of the Democratic puzzle get along easily with one another and the possibility of getting caught in a political cross fire is large. The second risk is that pleasing all of those constituencies sufficiently to win the Democratic nomination might well leave Mondale looking overpromised when the electoral base widens in the general election.

Mondale dismisses the second of those risks. “I want everybody to repair to my cause,” he says, “the labor movement, minorities, the Jewish community, farmers, students, everybody. I’m trying to get all the support I can get. I don’t think there’s anything tawdry or sinister about it. There’s a new theory I hear that the only way I can justify my position is to spend the next year offending people who would like to support me. That’s a theory of politics I don’t intend to participate in. “

The first of those risks, however, has already ceased being speculation and has become a prominent early chapter in Mondale-for-President history. The place is Chicago and the date March 27, Palm Sunday. Mondale is here campaigning with the black Democratic mayoral candidate Harold Washington. In the primary election, Mondale backed Richard M. Daley, one of Washington’s white opponents, and when Mondale first called to offer his help in the general election, Washington took eight days to return the call. Their campaign staffs eventually arranged today’s half-day of joint appearances.

Everything goes as planned until Mondale’s and Washington’s 11:30 A.M. drop-in at the Palm Sunday services of St. Pascal’s, on the city’s largely Polish northwest side. It is the kind of white working-class neighborhood where Mondale is thought to be strong and Washington is known to be worse than weak. When their campaign caravan stops 100 yards up the street from St. Pascal’s, 150 demonstrators favoring Bernard Epton, a millionaire lawyer and businessman, and carrying “EPTON” posters are waiting on the church’s front steps. The next 15 minutes provide the raw material for a 15-second film clip that will run over and over again during the following week as the Chicago election becomes a lead story on the evening news. All of it features Walter Mondale, trapped in a political no man’s land between two warring factions, both of whose votes he hopes to comerner.

The clip begins with Mondale and Washington making their way between angry demonstrators in the company of the parish priest. Shouts of “baby killers” and “not in our church” are drowned on the sound track by chants of “Epton, Epton, Epton.” In St. Pascal’s outer lobby, Mondale and Washington are shown huddling while their campaign aides decide whether to go inside – thereby disrupting the service – or simply backtrack to their cars and leave. Off camera, a teen-age girl 10 feet from Mondale is shouting at him. She has run in from the church’s Easter pageant rehearsal and is dressed in a fluffy, pink head-to-toe bunny costume, complete with floppy pink ears. “This is a church,” she screams. “This is a church.” The final sequence in the next week’s film clip is shot from the front and shows Mondale and Washington, having decided to leave, descending the church steps with the taunting crowd massed on all sides. As he has throughout, Mondale appears contained, jowly, tired and dignified.

After the camera is off, Washington and Mondale walk on opposite sides of the cars. Most of the hubbub follows Washington. For a moment, Mondale is by himself on the edge of the crowd and he is approached by a middle-aged man identifying himself as “a Norwegian.” The Norwegian is furious. “I’m ashamed of you, Mondale,” he shouts. “What’d Washington’s people ever do for us?” Mondale ignores the comment. Several seconds later, two younger men step up and address him as “Mr. Vice President.” They want to shake his hand and Mondale obliges before driving off between two lines of bobbing Epton posters.

An hour later, Mondale is at O’Hare Airport, headed for a week’s rest back on Lowell Street and then a push in Massachusetts for the state party convention straw poll there on April 9. Mondale will win in Massachusetts by a fat margin and on April 12 Harold Washington will win by a slim one in Chicago. By then, a dilemma similar to Chicago is brewing in Philadelphia, where a black, W. Wilson Goode, is running against a white, former Mayor Frank L. Rizzo, in the Democratic Mayor’s primary, which Goode later wins. This time, Mondale made no endorsement. According to several published reports, his heart was with Goode but his two principal Philadelphia fund-raisers were backing Rizzo.

It is hard to please all of your friends at once and, leaving Chicago on March 27, Mondale seems relieved to be rid of the obligation for at least the moment. He is glad to be offstage and headed home. In the airport, a reporter he knows approaches him, looking for a quote about what happened at St. Pascal’s. “What’d you think?” the reporter asks, motioning vaguely back in the direction of the city.

Mondale shakes his head as he answers. “That was somethin’,” he says, “wasn’t it?”

His response is the same as after the adulation of Atlanta 19 days earlier, only this time there is no hint of self-satisfaction in his voice. Chicago has been an object lesson and, despite his folksy nonchalance, Walter Mondale takes such lessons very seriously. He hears the footsteps behind him, even if it is too early in the race to tell if they are his own or someone else’s.

The Strategy: Getting off to a fast start

The shape of Walter Mondale’s campaign for the Democratic Presidential nomination, like those of his competitors, has been dictated by a series of mid-term 1982 “reforms” drastically reshuffling the political calendar for 1984. The new arrangement is commonly described as “front loaded” and the description is, if anything, an understatement. Between Feb. 27 and the end of March 1984, nine states plan to hold primaries and 20 binding caucuses, at which 46 percent of the delegates to the national convention are to be chosen.

In 1980, only 2 percent had been. This “reformed” calendar rewards the weight of sheer logistical mass more than any in recent political memory. The possibilities of a dark horse emerging after early victories are less than minimal, and Mondale’s strategists estimate that those first 10 weeks of 1984 will cost at least $4 million above campaign overhead. It is already considered far too late to seriously enter the race.

As of March 31, 1983, the $2 million raised by Mondale for President was nearly twice as much as raised by his nearest competitor. All 50 states have contributed to him, but New York, California, Minnesota, Florida, Maryland and the District of Columbia are his leading sources. Full-time fundraisers are stationed in New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Minneapolis, Washington and Boston.

The Mondale campaign projects raising $26 million in contributions and Federal matching funds over the next 18 months and, when the next Federal Election Commision reports are filed, on the last day of this month, expects to have a cumulative total of between $4 million and $4.5 million.

Mondale’s net disbursements are also almost twice those of his nearest competitor, and his campaign currently employs 90 staff members and 10 independent consultants, many of them veterans of the two Carter-Mondale campaigns or the Mondale Vice Presidency. Campaign organizers are stationed in 10 states. Though national preference polls mean little this early in the race, Mondale has led his current competitors in all except one of those published since December 1982.

Prior to the official formation of Mondale for President early this year, his campaign in effect existed as the Committee for the Future of America, a Political Action Committee whose role culminated in the 1982 elections. Though he now repeatedly denounces the influence of PACs on the political process, in its two years of existence, Mondale’s Committee for the Future of America raised and spent $2 million, financed much of Mondale’s considerable travel, and contributed $224,000 to 178 Democratic House and Senate candidates. By virtue of that 1982 effort and his years of party spadework when Vice President, Mondale has also started this race with a significant lead in favors owed and favorable impressions made among the “party activists” his campaign sees as central to the “leadership process.”

The campaign leadership responsible for Mondale’s early lead is full of faces with which he i.s by and large very familiar:

JAMES A. JOHNSON, 39, acting campaign chairman, sits at the apex of the organization. A Minnesotan and a Norwegian, his Public Strategies consulting firm has its Washington office within those of Winston & Strawn, Mondale’s law firm. Johnson began working for Mondale in 1972 and helped set up the abortive Presidential effort of 1974. In 1976, he was deputy director of the Vice-Presidential campaign and then Mondale’s executive assistant in the White House.

RICHARD MOE, 47, counselor and senior political adviser, first worked for Mondale in 1972 as his Senate administrative assistant. He directed the 1976 Vice Presidential campaign and then served as Mondale’s chief of staff in the White House.

JOHN R. REILLY, 55, counselor and senior political adviser, has, like Moe, no staff role. He is a senior partner in Winston & Strawn’s Washington office. He and Mondale first met in 1959 when Reilly was working for John Kennedy. Reilly supported Mondale’s 1974 efforts and traveled with him during the 1976 and 1980 general elections.

MICHAEL B. BERMAN, 44, campaign treasurer, has been with Mondale since 1964, when Mondale was chairman of the Minnesota JohnsonHumphrey campaign. Long considered Mondale’s craftiest political operative, Berman was counsel during the Vice Presidency. Like Moe and Johnson, he is from Minnesota.

ROBERT G. BECKEL, 34, campaign manager, is the inner circle’s only newcomer. He ran Texas for Carter in 1980, and in the Carter White House was in charge of Congressional liaison for State Department issues. He is now the Mondale campaign’s principal daily overseer and nuts-and-bolts man.

MAXINE ISAACS, 35, deputy campaign manager and press secretary, started in Mondale’s Senate office in 1973. She was deputy press secretary for the Vice Presidency and campaign press secretary in 1980.

REBECCA MCGOWAN, 35, deputy campaign manager and executive assistant, started on Joan Mondale’s staff In 1976 and then became director of scheduling and advance for the Vice President’s office. She now does essentially the same job that Johnson did for Mondale in the White House. The strategy developed by Mondale for President to maintain and maximize his early advantages has six basic tenets:

• 1. Accelerate the pace of campaigning. Mondale’s strategists believe they can sap the competition by forcing them to spend their resources early and often. They expect that logistics alone may well make it a two-person race before the end of the year, certainly by April of 1984. As things currently stand, that second candidate looks to be John Glenn. Though the Ohio Senator’s campaign apparatus has been slow at putting together the ground floor of a national effort, Glenn’s astronaut past lends his candidacy a celebrity sufficient to nullify a lot of his organizational shortcomings.

• 2. Nationalize the contest. Mondale’s campaign has sought to make everyone run all over the country from the outset, thereby dispersing his opponents’ efforts at concentrated organizing and, at the same time, using Mondale’s strength in some very visible states to lever open others.

• 3. Focus on the future. The Democratic showing in 1980 was a disaster and lt was led by a ticket on which Walter Mondale was No. 2. The less Jimmy Carter is talked about, the better. The issue the Mondale campaign wants to talk about ls what to do now, not what was done back then.

• 4. Sharpen Mondale’s contrasts with Reagan. It is believed by Mondale’s strategists that Democrats want a clear option to Reagan and that accentuating those numerous differences is a key to winning.

• 5. Emphasize the difficulties of the Presidency. Mondale’s four years in the White House under Jimmy Carter have left him with a reservoir of on-the-job training none of his Democratic competitors can match. The more difficult the job is perceived to be, the more attractive Walter Mon-. dale’s experience will seem.

• 6. Underscore the Democratic Party consensus. The Mondale campaign believes that there ls both a fundamental set of agreements underlying the party and that he is the candidate most naturally suited to represent them. Mondale must run as the candidate of all of the party and has done so since the beginning.

Of all the various Democratic Party constituencies to which Mondale hopes his mainstreamness will appeal, none is more strategically positioned this year than the A.F.L.-C.I.O. Having felt its influence was squandered in previous elections by making no endorsement in the primaries, organized labor intends in this election to endorse a candidate by late this year. Most experts use that labor movement endorsement to mark the opening of serious campaigning, and no one is in a better position to win it than Mondale. Such is Mondale’s advantage with labor that all the other candidates except Alan Cranston seem to be effectively ceding him the endorsement. Mondale’s strongest bloc in the A.F.L.-C.I.O. is the United Automobile Workers, the largest of its member unions. To them, “Fritz” is “a known commodity” who has been “with us” for a long time. The value of labor’s endorsement, however, may well be mixed, and the same may be true for a number of the other interest-group endorsements Mondale seeks. Unions are a decided negative among some sections of the electorate and, in recent years, union leaders have had problems delivering the vote of their membership in Presidential elections. Mondale wants their support anyway. “If I can get organized labor for me,” he says, “I’ll be proud of it. I don’t see how a President can affect to lead this country without their trust. I’ve been fighting for the rights of working men and women all my life. I think I’ve got a good argument.”

As popular as Mondale’s approach has proven with the U.A.W. and others, it is, of course, not without its critics. The longest running criticisms of Mondale focus on his political caution. Perhaps the most angry of those was made by a Minnesota D.F.L. activist in 1967. When informed that Mondale had had his appendix removed, the activist hoped out loud that “they put some guts in before they sewed him back up.” In 1974, another D.F.L. official struck something of the same note. “We had a lot of tough fights back there,” he noted, referring to Minnesota, “but somehow Fritz always managed to slip out and disappear . .. When the wind is blowing against him, he likes to wait for a more favorable tide.”

Mondale dismisses such criticism as more concerned with style than substance. “I’m not suicidal,” he retorts. “You can’t take on every issue, you have to husband your resources. At the same time, I challenge anybody to look at my record over the last 20 years and tell me anybody else who’s been in more controversial issues than I have.”

In the present tense, both Mondale’s campaign and its approach receive criticism as well. Most of it is still given on a not-for-attribution basis. A typical complaint is voiced by a former staff member at the Carter White House who is not currently a Mondale supporter. “You know,” he says about Mondale, “I’ve watched him over a long period of time and there is no doubt he’s one of the most decent people in politics. At the same time it’s no accident that I chose to work for someone else. I don’t think Mondale understands what has happened in this country. He’s a conventional Democratic politician who still believes the whole is equal to the sum of its parts. He’s the product of an earlier time. He’s not capable of disentangling himself from the ritual dance of nomination. He sees everything in isolated constituencies.”

In the present tense, both Mondale’s campaign and its approach receive criticism as well. Most of it is still given on a not-for-attribution basis. A typical complaint is voiced by a former staff member at the Carter White House who is not currently a Mondale supporter. “You know,” he says about Mondale, “I’ve watched him over a long period of time and there is no doubt he’s one of the most decent people in politics. At the same time it’s no accident that I chose to work for someone else. I don’t think Mondale understands what has happened in this country. He’s a conventional Democratic politician who still believes the whole is equal to the sum of its parts. He’s the product of an earlier time. He’s not capable of disentangling himself from the ritual dance of nomination. He sees everything in isolated constituencies.”

All of those criticisms and more will no doubt amplify. Front-runners must be attacked to be beaten. It seems to be Walter Mondale’s nomination to lose – at least until Iowa starts the caucusing process, 254 days from now.

Leave a Reply