As the Summer Project commenced, Allard Lowenstein at first kept to his last-minute strategy and stayed away from Mississippi, coming west to California to visit friends and catch up on a few other political odds and ends. He explained his decision to boycott as something his “conscience” demanded. He was not going to help SNCC do things he “disagreed with.” Better to start over again, he claimed. The decision was “irrevocable.”

His obstinacy began to reverse itself shortly. On Sunday, June 21, Andrew Goodman, a 20-year-old white college student from New York City who had arrived in Mississippi the day before, Mickey Schwerner, a 24–year-old white CORE staff member and Mississippi veteran also originally from New York City, and James Chaney, 19, a black civil rights worker from Meridian, Mississippi, drove from Meridian to Philadelphia, Mississippi, to inspect the charred ruins of the Mount Zion Baptist Church, attacked by white arsonists the week before. The Summer Project trio was stopped and arrested on their way out of Philadelphia. After being detained until after dark, they were released. Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman then disappeared and were never seen alive again. Two months later, the three young men’s bodies were found buried in the base of a remote earth-fill dam. Within 24 hours of their disappearance, it was already being assumed that they were dead.

In Mississippi, the news galvanized the Summer Project. In California, it provoked Allard Lowenstein into revoking the “irrevocable.” Under this kind of attack, Allard told his friends, everyone had to band together, whatever their differences. Lowenstein left for Mississippi immediately and would spend the summer there in a relatively inconspicuous position with the liberals’ legal assistance team.

The month of June had been officially designated “hospitality month” by the Mississippi state government. In Jackson, white men fired into black Henderson’s Cafe, wounding one Negro in the head. In Clinton, the black Church of the Holy Ghost was burned to the ground. In Hattiesburg, two cars belonging to civil rights workers were shot full of holes. In Hinds County, three civil rights workers were arrested and beaten by their jailers.

Dennis Sweeney was already in Jackson, preparing to accompany a select SNCC-led task force into McComb. The selection of Dennis Sweeney for McComb was testimony to the high regard in which he was held by SNCC, whatever his relationship with the suspect Lowenstein. SNCC’ s personnel rule was, the more volatile the place, the better the people who ought to be sent; under that logic, assignment to McComb was the highest rating a volunteer could have. McComb had the reputation of a rabid dog.

Before the summer was over, two-thirds of the state’s 70-odd racial bombings would happen within a half hour’s drive of the place. Located in Pike County, southwest of Jackson, the town was the trading and cultural center for surrounding Amite and Walthall counties as well. Large parts of the white population gave at least perfunctory obeisance to either the Ku Klux Klan, the White Citizens Council, or the Citizens for the Preservation of the White Race. “God wanted white people to live alone,” one local Citizens Council tract explained. “Negroes use their own bathrooms, the Negro has his own part of town to live in. This is called our Southern Way of Life. God had made us different and God knows best. … ONE DROP of Negro blood in your family could push it backward three thousand years in history.” Of some 15,000 voting-age blacks in Pike County, only 200 had been permitted to register to vote; in Amite County, of 5,000 blacks, only one was registered. Among Walthall’s 3,000 blacks, not even one could vote. In January, white night riders had swept through black McComb, firing into six houses and wounding a young boy.

Jackson might be the state capital, but if Mississippi ever had a heart, it was McComb.

McComb was also at the root of SNCC’s own history. When Bob Moses began the Mississippi Project in 1961, he opened his first black voter- education school in McComb. Within three months, he and the rest of the SNCC staff had been arrested, beaten, and were serving 90 days in the jail in Magnolia, Mississippi, Pike County’s seat. One of their local black supporters had been shot dead on the street by a white state legislator. When they finished their jail terms, the Project had decided to move out of Pike County to the Delta, which was said to be somewhat less brutal. The seven-person contingent, including Dennis Sweeney, would be the first civil rights workers in McComb in over two years.

When they were briefed in Jackson, the potential danger was emphasized. Anyone who wished could request a different assignment without stigma. “Anyone who goes in,” Bob Moses warned, “faces a high probability of death.” No minds changed. Both the McComb houses where the volunteers had first been scheduled to live had been dynamited two weeks earlier. In Magnolia, armed whites had begun practicing military drill in the courthouse square every Thursday night. SNCC people would be on their own with nothing but their visibility to protect them. Once again, the opportunity to withdraw was offered. Once again, no one took it.

Young Dennis Sweeney’s heart must have been in his throat. His compatriots from that summer remember Sweeney as “straightforward” and “enormously sincere.” He never complained and only showed his fear in the way he sometimes pressed his lips together.

He and the others opened the McComb Project during the first week of July, living in a rented freedom house on Wall Street in black McComb. On the evening of July 8, white McComb officially welcomed the “race mixers” who had just arrived in its midst. Dennis Sweeney and his fellow civil rights workers were all asleep. The air was hot and soggy, and the night outside the Wall Street house seemed to lurk.

Dennis was curled up in the living room on the bed closest to the front door. He didn’t hear the car screech to a halt in the driveway with its motor running. The first sounds he was conscious of were the clunk of a package being flung at the porch and then the squeal of the car’s getaway. Before his head cleared, eight sticks of dynamite exploded barely 10 feet away, tearing up a section of the driveway and collapsing the house’s front wall. Dennis was lifted up by the blast and dumped over with his mattress and bedboard on top of him. At first he couldn’t hear anything, but he saw shards of glass all over the floor and smelled cordite fumes. Once he extricated himself, he had to agree that they had been lucky. No one had been killed, and Dennis, the most seriously injured, had nothing more than a pair of badly concussed eardrums.

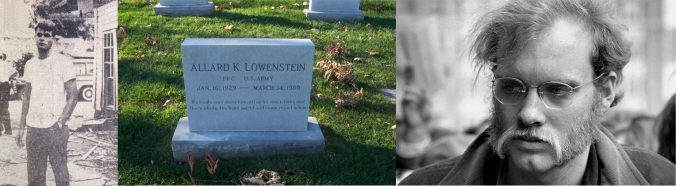

The next issue of the McComb Enterprise Journal carried a picture of Sweeney. In it, the handsome, 21-year-old integrationist invader from Oregon via California stood in front of the remains of the Wall Street freedom house, smiling grimly and with great resolve.

Two McComb policemen came over to investigate on the morning of July 9. A Northern newspaper reporter arrived as well. While the three of them were examining the damage, one of the cops reportedly grinned and shook his head. “Looks like termites to me,” he said.

Leave a Reply