New York Times Magazine – March 9, 1980

The enigma cloaking Jerry Brown only intensifies when he enters the room. There are few actual Brown supporters among the 200-odd Democrats who are squeezed into the small banquet hall. Most of them have come simply to gel a look at the reigning 41-year-old oddity in the 1980 Presidential race. The nation has only one two-term governor who follows a vegetarian diet and takes his rock-star girlfriend to Africa. The experience is what Brown himself calls “running an interesting third.”

The scene could have been in Iowa or New Hampshire, Maine or Massachusetts. Wherever Brown has taken his campaign, he has been successfully ignored by President Carter and Senator Edward M. Kennedy. Rated no higher than 7 percent in the polls nationally, he has long since ceased to be a regular part of the reported findings in major surveys. Fittingly for a man who is characterized by irony at almost every juncture in his private and political personalities, Jerry Brown has been left to run against himself, and he is trailing. The truth is that it is Brown’s image that is holding down third. Jerry Brown himself remains even more unknown, and further back than that.

As Californians have long known, the contradictions between expectation and reality lend an electricity to his performance that would ordinarily be denied someone most political commentators have buried in caricature. Wherever he appears, the voters get something very different from what they’d expected from Jerry Brown.

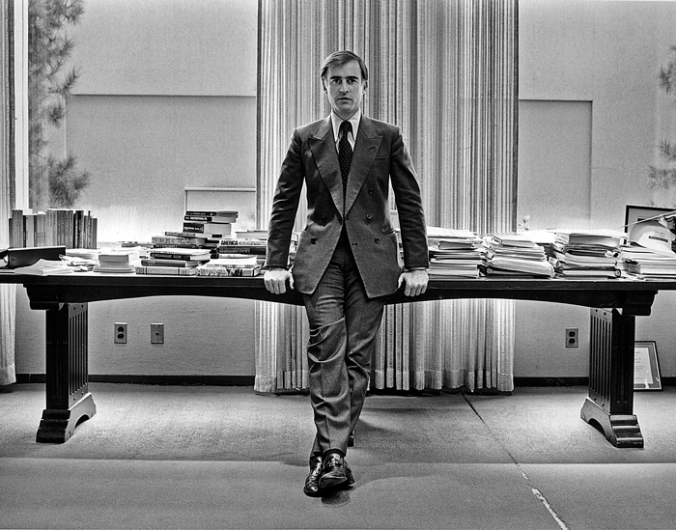

His appearance is the first surprise. The candidate who has been compared in print with a television character from outer space wears a three-piece stockbroker’s suit and is immediately regarded as much better looking than his photographs. He is taller than Jimmy Carter, younger looking than Ted Kennedy, and some in the audience say that, from his left side, he resembles Montgomery Clift.

His stump performance is even more unexpected. The man most often cartooned as wearing love beads and sitting on a prayer rug turns out to speak articulately without notes and to quote The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal from memory. Behind the podium, he is quick, cerebral and singular. Nothing in the legend of the California Flake preceding him prepares his listeners in the banquet hall in Clinton, Iowa, for the Jerry Brown who is a highly successful and shrewd second generation Irish Jesuit politician.

That he is clearly different from other politicians is apparent in the way he talks to a crowd; Jerry Brown has no intention of emoting himself into the Presidency. There is no attempt to arouse the feelings of the audience. Instead, he seems intent on capturing them with cutting abstraction and telling practical analysis. Jerry Brown has come to tell the citizens of Clinton how the world really is, and does so with a bluntness that at times verges on cynicism. “Santa Claus politicians” draped in “promises of guns, butter and tax cuts” are selling the future, he says. “We are,” he summarizes, “operating on a precarious mode that cannot continue. We have to change our government, our President, our hearts, and how we want to live.”

The small and weary contingent of press people following the Governor rouses at the reference to “hearts.” It, like a stray lick of hair, is the only word that doesn’t quite fit. They are not used to even that minimal a plucking of harpstrings from Brown, and indeed, spend much time privately debating how much of a “cold fish” he actually is.

Next to his obvious intelligence, the most distinctive of his skills on the stump is his eye contact. Whether shaking hands in the crowd, dancing through his set speech, or listening to questions, Jerry Brown’s eyes invariably look directly into those watching him. In some people, that might be a warm gesture equivalent to touching, but not in Brown. Neither is it hostile. Instead, the look is disturbingly neutral, like the man himself. Everything is information to Jerry Brown, to be digested and filed. At moments, this detachment couples with a shift of his jaw and an angling of his head that is almost a sneer.

That expression is Jerry Brown at his worst. It gives his face an air of arrogance, like a child prodigy or sanctimonious priest. Every lime those in the press contingent see his mouth warp like that, reporters wonder if everything derogatory that’s ever been said about Jerry Brown isn’t true after all.

No such doubts seem to assail the audience in Clinton. Jerry Brown receives prolonged applause when the event concludes, and a chorus of rave reviews. One Clinton City Councilman sums up the reaction. “He was very good,” the man responds when approached by the press for a comment. “He’s credible. What he says is the truth.”

No such doubts seem to assail the audience in Clinton. Jerry Brown receives prolonged applause when the event concludes, and a chorus of rave reviews. One Clinton City Councilman sums up the reaction. “He was very good,” the man responds when approached by the press for a comment. “He’s credible. What he says is the truth.”

It is in keeping with the irony dogging Jerry Brown’s footsteps that his consistently well-received performances have netted him so little. After expending close to a million dollars on full-scale campaigning in Iowa, Maine and New Hampshire, Jerry Brown has yet to win his first delegate to the Democratic National Convention. He dropped his efforts in Massachusetts before the votes were even counted in New Hampshire, where he received 10 percent of the vote, compared with Carter’s 49 percent and Kennedy’s 38 percent. He will skip the Southeastern primaries later this month, and has been disqualified for New York’s voting on March 25. His money is largely spent, and there are few obvious sources for new funds. Brown himself has gone $50,000 in personal debt, has pledged to keep campaigning if he has “to hitchhike,” and still thinks he can carry the party’s nomination – but will not be on the ballot again until April Fool’s Day in Wisconsin. There, he claims, he will run ahead of Jimmy Carter, but few if any take the threat seriously. One more zero there and his campaign will have diminished to no more than an effort to avoid embarrassment in his home-state primary in June.

The lesson is obvious. The Presidency is not won off in a comer battling your own image, successful or not. This is most surely not 1976, when the then-37- year-old political phenomenon tore a late swath through the effort of a triumphant but fading Jimmy Carter, winning five of six in the later primaries. Back then, there were those who said that if he’d only started his campaign earlier. he’d be the incumbent today. Such talk is largely forgotten now. Had he ever managed to get accepted as part of the same race as the others, he might have been a threat but, at the moment, that possibility seems to have vanished. Jerry Brown’s bandwagon continues, the same place it began, mired in a bog of public perceptions that offer him little opportunity to do more than spin his wheels.

The experience is frustrating. One afternoon in Iowa, Jerry Brown is fiddling with the radio dial in a rented Ford campaign car, in an attempt to locate some news accounts of his presence. Instead, he picks up little but reports of Ted Kennedy’s tour of the state going on at the same time. and nothing about himself. “Where am I?” Brown complains. The voice is both whiny and self-deprecating at the same time. It seems directed at the cosmos itself.

“Where am I?” he repeats.

No one in the car answers.

That some sort of political disappearance might eventually plague Jerry Brown has been implicit since he first entered the limelight, six years ago.

Like every major statewide figure in California during the last decade, Jerry Brown is a media politician. The closest things to entrenched political machines there amount to little more than cliques of celebrities who conspire to buy air time. Ronald Reagan, Jane Fonda, S. I. Hayakawa, John Tunney and Jerry Brown are all obvious end products of such a political training ground. Edmund G. Brown Jr. narrowly won his first term as Governor in 1974 with a strategy that ignored content and stressed the name recognition Brown derived from his famous father’s two terms as Governor from 1958-66. Jerry Brown then immediately began to break out on his own to shape a public identity ln what now appears to have been the riskiest possible manner.

The people who constitute the nation’s image and information industries generally file their products under familiar categories. Since first becoming Governor, Jerry Brown’s strategy has always been to be one of a kind, complex, to defy categorization, to op erate situation by situation and in a pattern that he calls “wide-based,” that his supporters call “visionary,” and that reporters who are older than he call “all over the block.” The seeds of his present reverses have been germinating ever since he commenced doing things that hadn’t been done before.

He refused to live in the brand-new $1.3 million Governor’s mansion. He slept on an unsupported mattress in a $275-a-month apartment across the street from his office, and he abandoned the traditional state executive’s Cadillac for a four-door Plymouth sedan. He then introduced the phrase “small is beautiful” to the American political vocabulary, made a point of frugality to the extent of bragging about being personally “cheap,” and kept his principal 1974 campaign promise never to sign an increase in state taxes. After two years in office, Jerry Brown ended up having the highest approval ratings, across the spectrum of both parties, in the history of California political polling. The national notoriety acquired in the process propelled him into the role of prime Presidential contender before the end of the 1976 primary season. In 1978, Brown went on to win re-election by one of the largest vote margins in California history.

Since then, things have changed drastically. His once successful one-of-a-kindness has, over the last two years, been increasingly likened to a loose screw rattling around in an empty drawer. On a national level, the two words in widest circulation about Edmund G. Brown Jr. today are “opportunist” and “flake.” That the latter of those words connotes someone who could not distinguish an opportunity if it ran over him on the freeway, and the former someone in a constant state of calculated maneuver for his own narrow and well-perceived advantage, illustrates the contradictions that labeling him typically produces.

There seem to be four primary conditions impelling Jerry Brown into his present corner:

The first is that he is a genuinely different politician who is in fact hard to comprehend and who possesses a vision of the national dilemma to which he is intensely committed.

The established standards for locating and judging office seekers assume a one-dimensional spectrum that runs from left to right, and a single, continuously held position along that spectrum. Jerry Brown himself considers such expectations of consistency “unrealistic” in their failure to recognize the importance of human growth, and instead talks about his Governorship as a “learning experience.” He has pursued this “education” with a style that combines long periods of rumination with moments of sudden and swift decision making characterized at Its best by Insight, and a shrewd sense of timing and the necessity of playing interests off against each other. At Its worst, it is whimsical and somewhat childish. Brown’s own gnawing intellect never seems to bring finality to its judgments, and his political positions have consequently shifted and evolved throughout his career. While such intellectual qualities might be considered “mature” and be respected in any other realm of work, they are considered risky and suspect when evidenced by politicians. In their latest formulation, the Governor’s stances reject the validity of left-right politics in its entirety.

His struggling Presidential campaign has been predicated on nothing less than this: the formulation of a new Democratic coalition. He Intends to attract what has heretofore been thought of as the economic right by calling for a balanced budget and warning direly of “excess private and public debt,” and inflation. He then intends to join this base with the social left by adopting the toughest of the Democratic stances against nuclear power, pointing out his own emotional membership In the Vietnam generation, and talking about “the planet” and preserving its “life systems.” Strategically, joining the two Democratic ideological poles amounts to staking out a political circle that iso lates what has been traditionally thought of as the party’s center.

That such a new approach should be difficult to understand is a given. That it is even more so in Brown’s case is, ironically enough for a man as obsessed as he is with information and communication, his own fault.

On the whole, Jerry Brown has done a bad job of explaining himself. When not running for election, he has gained a reputation for talking to the reporters who cover him only at his convenience, and on his own terms. Even then he has been only occasionally declarative, and often tauntingly obtuse. When his fellow politicians and those in the media have become uneasy about this, any other political figure would most likely have grinned and greased people enough to keep them soothed. Jerry Brown’s intense differentness won’t let him do that, and the results are obvious.

That aspect of the California Governor’s personality amounts to the second source of his present image dilemma. In reality, this part of Edmund G. Brown Jr. includes a range of behavior that momentarily contradicts his customary public charm. At its least abrasive, it is an emotional and intellectual need to stay at a distance and challenge the assumptions that are being used to judge him. Rather than mollify, Brown tweaks and pokes at people’s suspicions. In this same trait’s darker reaches, he is said to be contrary, cold, hard on those around him, unappreciative of any priorities but his own, and rude.

This part of Jerry Brown evokes no sympathy at all. As a result, when his image began sputtering, a lot of people were ready to help it nose-dive.

Ironically enough, the third Ingredient in the Brown identity crisis has been his own early campaign organization. Unlike both Kennedy and Carter, Jerry Brown started without either a standing force to be sent into the field, or the money to feed It. During the slow process of putting itself together from scratch, the Brown campaign had a surplus of public-relations disasters spanning September through November. Since then, it has righted Itself, tiut only after significant damage had been done. The classic of these stumbles has gone down in campaign lore as The Swami’s Endorsement.

It is mid-November 1979, and Jerry Brown is in Boston. At this point, “CBS Evening News” has already greeted his announcement of candidacy as a mixture of “Boy Scout Oath” and “Star Wars.” Love beads, prayer rugs and “Governor Moonbeam” references have begun creeping into the political cartoons. He Is in town to address a holistic health convention and does so thoughtfully and with great intelligence. After Brown finishes, word reaches his entourage that the International Transpersonal Association’s meeting is also convened this weekend. At the moment, they are across town and the conference is being addressed by Swami Muktananda. The decision is made for the Governor to drop by and fill in one of his schedule’s blank spaces. Brown arrives there with both print press and a CBS reporter plus camera in tow; the highlights of what follows are captured on videotape.

Brown stands at the door closest to the stage for half an hour, waiting for the swami to introduce him to the large audience. Brown is well lighted, and clearly uncomfortable. At long last the swami, who has been answering audience questions through a translator, says something and makes a gesture of his hand. Translated, his statement ends with “Here is our great leader, Jerry Brown.” Before Brown has even begun moving out onto the platform to address the association, the swami immediately returns to the business at hand and fields another question about Hindu theology. The appearance is over. None of the people in the hall have even got a glimpse of Brown himself. When the footage runs on Walter Cronkite’s evening news, the effect on Brown’s image is to be caught, freeze frame, being ignored while he fumbles around at the feet of the guru. During the next month, the bulk of the coverage in the national political press treats him with all the respect accorded a young Harold Stassen.

The tendency to dismiss him so quickly and easily has been reinforced by the fourth and final difficulty that has plagued the Brown image, and made most anything written about him believable.

Edmund G. Brown Jr. is from California.

People elsewhere forget that California has the eighth largest government in the world, and leads the nation in both agriculture and advanced technology. They remember Jim Jones, the Hillside Strangler, coke spoons, nude beaches, topless shoeshine girls and hot tubs. It is, as Governor Brown readily admits, “a state with 10,000 or 12,000 of everything.” When you are the chosen chief executive of such a collection, people elsewhere tend overwhelmingly to hold you responsible for all of it.

The “berserk Californian” rap on Jerry Brown obscures a lot. Judged on quickness of mind, ability to translate abstractions into realities and organize random events into comprehensible abstract patterns, he is the most obviously intelligent candidate in the Presidential race. His demonstrations of these qualities are his foremost, and perhaps only, remaining political asset.

To know Jerry Brown at his best, consider an 8 o’clock breakfast meeting of the South Shore Chamber of Commerce Inc. in Quincy, Mass. Most of his listeners are businessmen. From the first moment he is up there, Jerry Brown obviously feels both confident and at home. Afterward, when the swarm of accompanying reporters fans out into the audience to gather responses before the motorcade departs, every recorded comment is positive. The most articulate response comes from the college-educated wife of an international business consultant. “I think he’s an intellectual,” she comments. “If you just sit and listen to him speak, you find that this man does not hem and haw, does not grasp for words. His mind is propelled in the direction of clarity…He has certainly altered my opinion of him…”

That many in the audience feel this way is obvious even before the quotes are collected. The press guesses it from the way The Question is asked. It is the last he will take during this performance.

The Question is the one that comes up everywhere Jerry Brown goes and is guaranteed to be on the minds of just about every person in every audience, articulated or not. In front of this now. appreciative group, it is phrased gently.

“Governor,” the questioner begins tentatively, “we know you trained for the priesthood, and I wonder if you would give us your views on the extent you think the private morality of a Presidential candidate affects his qualification for that office?”

Brown recognizes the gist of the inquiry immediately. “Well,” he chuckles, rubbing his hands together, “I’m not going to tell you about my trip to Africa.” The tension generated by the audience’s anticipation breaks into a ripple of hearty laughter. “I try,” Brown continues, “to keep my private life as private as I can.” This is followed by vigorous applause. What he says then is more serious, and he makes this point, in some version or another, at each stop. It is Jerry Brown at his most publicly genuine. “The very nature of private,” he explains, “is its distinction from public. In order to be human and to be sane, a person in public life who becomes a commodity for media exchange must draw a zone of privacy somewhere. Otherwise, the person has no basic mental harmony or ability to think or reflect or make good sense of himself.”

Brown recognizes the gist of the inquiry immediately. “Well,” he chuckles, rubbing his hands together, “I’m not going to tell you about my trip to Africa.” The tension generated by the audience’s anticipation breaks into a ripple of hearty laughter. “I try,” Brown continues, “to keep my private life as private as I can.” This is followed by vigorous applause. What he says then is more serious, and he makes this point, in some version or another, at each stop. It is Jerry Brown at his most publicly genuine. “The very nature of private,” he explains, “is its distinction from public. In order to be human and to be sane, a person in public life who becomes a commodity for media exchange must draw a zone of privacy somewhere. Otherwise, the person has no basic mental harmony or ability to think or reflect or make good sense of himself.”

Brown receives a standing ovation, shakes hands for several minutes, and then departs for two more stops in Boston and another six in New Hamp shire before finally resting for the night.

That evening, like every other, he will place several calls to California from his motel room. There is no way of telling when one of them is to Linda Ronstadt’s house in Malibu.

What is known is that Jerry Brown makes such calls with a discernible regularity, and that Linda is home at 8 or 10 P.M., California time, to answer them.

Linda Ronstadt has been part of Jerry Brown’s image ever since he and the 33-year-old singer shared his safari vacation to Africa in the spring of 1979. That expedition rapidly deteriorated into a media chase and raised several months’ worth of speculation about the Governor and Linda’s nonexistent plans for marriage.

One obvious point about the nature of their relationship is that Linda Ronstadt has been a critical part or the Brown for President fund-raising effort and, through her participation and organization of benefit concerts, is responsible for a good $400,000 of the candidate’s recorded pledges. Another point is that her arrival on the scene has largely freed Brown of the questions about his sexual life that might plague any single, 41-year-old male candidate.

On the face of it, the liaison reads like a treatment for a Hollywood musical. Handsome Governor meets beautiful singer, and sparks fly. In real life, the two were introduced to each other shortly after Brown became Governor by Frank and Lucy Casado, proprietors of Lucy’s El Adobe Cafe, a Los Angeles Mexican restaurant where Brown often dines. According to Miss Ronstadt, the attraction was immediate. “I looked at him,” she remembers, “and said, ‘Hey, he’s cute. I wonder whether I can get a date.’ “

Little else is known about their courtship except that it was conducted at the mercy of Brown’s schedule. What is known is that the Governor’s famous blue Plymouth eventually began dropping him late at night in Malibu, and picking him up there the next morning for the 45-minute ride over to the home he owns in Laurel Canyon, to work on state business. One early-morning visitor to Miss Ronstadt’s house reported being met at the door by Brown, wrapped in a towel.

According to one friend Brown discussed it with, the decision to open his relationship with Linda Ronstadt to the mauling of public curiosity by going to Africa with her was an excruciating one. On the one hand, the Governor was torn between his own characteristic trepidation about exposing his private self and, on the other, with his desire to behave like a normal human and take a vacation trip with the woman in his life.

According to one friend Brown discussed it with, the decision to open his relationship with Linda Ronstadt to the mauling of public curiosity by going to Africa with her was an excruciating one. On the one hand, the Governor was torn between his own characteristic trepidation about exposing his private self and, on the other, with his desire to behave like a normal human and take a vacation trip with the woman in his life.

According to all available accounts, their relationship is, by and large, tender, relaxed, loving and marked by both commitment and mutual respect. That the relationship has survived and prospered in the eight months since the African gossip melee is obvious at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas in late December. Miss Ronstadt and several other acts are presenting the second of two benefit concerts for Brown’s Presidential campaign. The 7,400.seat house is sold out, and Brown himself is watching from the third row. Toward the end of her set, Miss Ronstadt breaks the format to complain that, over the last two months of campaigning, she’s almost forgotten what Brown looks like. “He came back yesterday,” Linda explains. “He’s going to make it better now.” Then she dedicates one of her final songs to the man for whom the concert is being given.

The song is entitled “My Boyfriend’s Back.”

Those at the Aladdin that night describe Brown as “visibly moved” by Linda’s gesture. When the song is done, he leaves his seat and goes through the stage door. The spotlight follows Miss Ronstadt at the set’s conclusion and accidentally captures the two of them necking offstage. When questioned afterward, Linda Ronstadt gives one of the fullest explanations of their relationship on record. “Whenever people write about us,” she says, “they always wonder if there is a political motive. We just like each other, that’s all.”

On Christmas Eve, Linda and Jerry privately attend midnight mass with the Casados. After Christmas, they travel to the Zen Center, a northern California retreat Brown visits occasionally. They stay there for three days.

In understanding the wall Jerry Brown has thrown up around his private life, it must always be remembered that he is the son of a politician, with ample direct emotional experience to justify his remarks about the potentially destructive effects of politics on the people who must live a life inside it. In his childhood, he posed along with everyone else in the family for his father’s campaign brochures, and ended up eating a good portion of his meals with neighbors.

Given the sense of personal violation he most likely endured as a child, it is unlikely that his present position on revealing personal subjects will change. “I think the question is proper,” he explains, “and I think my answer is proper as well.”

Religion is another subject Jerry Brown will not talk about on the record. It is a Friday afternoon in Brown’s Laurel Canyon home. Tables everywhere are piled with manila files full of state business. Today Jerry Brown is doing one-on-one sit-down interviews. At the moment, he is talking with a print reporter, and a TV crew is waiting out in the driveway. The print reporter is trying to get Jerry Brown to say whether he is still a Catholic or not.

Brown declines to answer. “I’m not going to express my spiritual views of the world. I think those are best left in the secular realm. If you exploit your spiritual life, you run the risk of destroying it.”

“Don’t we have a right to know?” the reporter presses.

In this instance, as in most when pressed, Jerry Brown responds with an aggressiveness that, while friendly, brings an edge to his voice that might sound snide if he pushed it any further.

“Whether I believe Mary is the mediatrix of all graces?” he questions back. “Or whether I agree with Father Küng or the Pope in their present theological controversy?”

It is a common Jerry Brown verbal technique to deflect requests for precise declarations with demonstrations of knowledge about the general subject. In this case, it doesn’t work, and the Governor is cornered into giving out the smallest piece of information possible. “Obviously,” he sighs, “my whole life has been profoundly affected by religion.”

No larger understatement about Jerry Brown could be made.

In locating Brown, it is essential to remember that his first choice as a young man was to abandon the world of politics in which he’d been raised and to train instead for the priesthood. At the age of 18, California’s future Governor began more than three years of monklike life in a Jesuit seminary in Los Gatos, Calif. During much of that time, he was allowed to speak during only 30 minutes of the day, and was allowed visits from his family only once a month. Although the outside world eventually drew him back, for a long time he lived without it, and that withdrawal has marked him ever since.

In locating Brown, it is essential to remember that his first choice as a young man was to abandon the world of politics in which he’d been raised and to train instead for the priesthood. At the age of 18, California’s future Governor began more than three years of monklike life in a Jesuit seminary in Los Gatos, Calif. During much of that time, he was allowed to speak during only 30 minutes of the day, and was allowed visits from his family only once a month. Although the outside world eventually drew him back, for a long time he lived without it, and that withdrawal has marked him ever since.

The distance in his manner smacks of a priest’s preoccupation and elevation from surrounding circumstance. His Jesuit training shows in the intensity he has brought to the craft of politics as well. Brown is, by all accounts, a man inseparable from his work. His cerebral quality, his need to generalize from specifics, and his precise skepticism are all stereotypically Jesuitical as well. When asked about marriage, he frequently answers by talking about how the realms of politics and family have immense difficulty coexisting, and how that, for him, politics comes first. Were he celibate, Brown could easily be a priest talking about betrothal to the church.

Speculation about his present religious affiliation has centered around his visits to California’s Zen Center. It is base of operations for one of the few legitimate Zen roshis, or abbots, outside of Japan. The center runs two well-known retreats that serve a constituency of people who have interests varying from Buddhism to just getting away from L.A. for several days. Richard Baker, the roshi, is known for his lively intelligence, and the center’s facility at Green Gulch in Marin County is also known as the locale of one or the closest things to an intellectual salon functioning in California.

When the print reporter asks about Zen in the interview at his Laurel Canyon home, Jerry Brown says his connection to the center is simply a function of his friendship with Baker the roshi. There is no religious significance. “It’s one place where I can get away from reporters like you,” he explains, “and get a few hours of silence to reflect and quietly spend time in a way that the normal sound and fury of the life I’m involved in does not permit.”

Since the connections with both his religious retreat and his woman seem to be experiences from which he draws strength, it Is perhaps fitting that Jerry Brown should be with Linda at the roshi’s center when he gets news of what is undoubtedly the biggest disappointment of the 1980 campaign.

Brown, Linda Ronstadt, assorted staff and various experts have been at the Green Gulch facility for more than two days when word comes that Carter has pulled out of the nationally televised debates that had been planned for Des Moines on Jan. 7. The Des Moines debate is, until that moment, the linchpin of Jerry Brown’s strategy, his first and perhaps only opportunity to pull his campaign out of the national bog in which it has consistently lingered. There is wide belief among reporters who have covered Brown, and watched both Kennedy and Carter as well, that, had the debate actually taken place, the California Governor could have inflicted damage on both his opponents. According to a person present at the time, the debate’s sudden collapse was received by Jerry Brown at the Zen Center with disappointment and, after a few hours, a growing air of exasperation. Eventually, Brown focused on castigating Carter whenever the subject came up, and sounded almost whiny. On one such occasion, roshi Baker interrupted.

Like Brown, Baker likes to challenge assumptions and pop intellectual bubbles.

There was no sense in blaming Jimmy Carter, the roshi reportedly chided Brown gently. If the Governor himself had been in Carter’s position, wouldn’t he have done the same thing?

The roshi perceives his friend the Governor with great accuracy.

Like Ted Kennedy, Jerry Brown is a politician by birth. His paternal lessons included all the techniques of maneuver, parry, posture, resignation and backroom bargain striking. His father, Edmund G. (Pat) Brown, was as good at them as any Democrat in the history of California. In that sense, Jerry Brown is and always has been his father’s son.

In almost every other measurement, there is great irony in Jerry’s being Pat’s offspring. Pat built highways and is still given credit for the well-fed excellence of the state university system; he was the fountainhead of post-Korean War public-works liberalism. Jerry scoffs at liberal “money throwing,” Is suspicious of government, has curtailed highway construction in favor of mass transit and has forced the University of California to live with budget reductions, Pat’s fellow politicians loved him. At a rule, they are at best uneasy with Jerry.

Like the deterioration of his national image, most of the present suspicion characterizing Brown’s relations with his fellow politicians dates largely from June 1978, and the California primary-election aftermath. At this time Proposition 13, the property tax initiative, became part of the national political lexicon. Its passage rocked all of the established elements of California Democratic power, and, when all was said and done, left Jerry Brown with the label “opportunist.”

Almost every state Democratic office holder up to and including Brown opposed Proposition 13, as well as all the state’s unions, teacher groups, school systems and local governments. When the initiative garnered 65 percent of the vote, politicians throughout the state scrambled to cover themselves. The next day’s election editions were full of speculation that Brown was “in trouble,” and discussed expectations that Evelle Younger, Brown’s Republican gubernatorial opponent in the general election, would use Proposition 13 on the Governor like a bludgeon when he returned from a two-week postelection vacation in Hawaii.

During those two weeks, Brown proceeded to confound the prognosticators with one of the slickest pieces of political maneuver in the history of the state. The Governor repeated his previous opposition to “13” without emphasis, but then went on to say that, now that it was the law, his job was to make “13” work. ln the immediate postelection frenzy, as local government after local government weighed in with predictions of drastic reductions, closed schools and eventual bankruptcy, Jerry Brown appeared regularly on TV doling out pieces of the state surplus to cover their needs. By the time Evelle Younger came back from vacation, there was no bludgeon left to wield. ln November, Jerry Brown won a second term by a record two million votes. When polled, 40 percent of those in the state assumed that he had been for Proposition 13 in the first place.

Despite the overwhelming success his handling of the situation brought, him in California, his response to” 13″ has attached an ever-present measure of distrust to the Brown image elsewhere. Brown explains his turnabout by saying that he opposed “13” because it was bad legislation that gave most tax advantages to business. Once it was state law, however, he was obliged by his oath of office to do his best to make it work, and he did.

Nonetheless, Proposition 13 has hurt him. The downturn in his image became dramatic after its advent, and dogs him still. Largely as a result of his behavior in 1978, he has been tagged as this election’s “opportunist.” Trapped once again in irony, Jerry Brown, judged too proficient at doing precisely what the public has traditionally demanded of politicians, is being denied the opportunity to do so again. Politics is a form of combat and, in the words of one veteran journalist, “Brown can charge through any crack wide enough to show light.’ The only mistake may be in assuming that this quality, in and of itself, is enough to distinguish him from anyone else who has ever sought the job he seeks.

The features that do distinguish Brown’s opportunism from that of the rest are present in what he perceives the 1980 Presidential “opportunity” to be, and the risks he has assumed to try to take advantage of it. In simple summary, Brown perceives the nation, the Western world and the planet itself at a historic crossroads. The American industrial machine is on a steady downslide as its competitive allies gain economic supremacy. on utilizing more than 40 percent of the world’s raw materials, at precisely the same moment when suppliers have their greatest historical advantage. As a result, the United States will have increasing difficulties sustaining itself. Brown claims that power and productivity have, in turn, both altered fundamentally, and that our thinking about them must alter too.

The features that do distinguish Brown’s opportunism from that of the rest are present in what he perceives the 1980 Presidential “opportunity” to be, and the risks he has assumed to try to take advantage of it. In simple summary, Brown perceives the nation, the Western world and the planet itself at a historic crossroads. The American industrial machine is on a steady downslide as its competitive allies gain economic supremacy. on utilizing more than 40 percent of the world’s raw materials, at precisely the same moment when suppliers have their greatest historical advantage. As a result, the United States will have increasing difficulties sustaining itself. Brown claims that power and productivity have, in turn, both altered fundamentally, and that our thinking about them must alter too.

Jerry Brown believes the prime quality necessary in a candidate for President in 1980 is “an understanding of the economic and technological changes that confront the nation.” “The country faces a slowdown that will require a new cooperative effort,” he argues. “The next President should be able to mobilize a governing coalition to bring about the reindustrialization of America…We need more invention, more craft, more skill, and a commitment to a sustainable future. We need to reverse both our productivity decline and our mistreatment of the systems of nature upon which all wealth is ultimately based. This all calls for fresh thinking and a new fiscal discipline. As far as I can see, I am the only candidate in the race who offers both.”

The risks involved in basing a Presidential campaign on the assumption that the course of history is flowing in your direction are as obvious as they are monumental. On the few occasions when his Democratic opponents have even mentioned his name, they have done so with humorous reference to his futuristic qualities.

The political erosion Jerry Brown has suffered as a consequence has been widely noted in his home state. In a mid-February poll, he got only 11 percent of the vote among California Democrats. Many Democratic Party regulars speculate publicly that his Presidential run may damage his political base irretrievably and extinguish any possibility of a third gubernatorial term in 1982.

Seeking the 1980 Democratic nomination may now rank as the biggest risk that Jerry Brown has ever taken. Early in the year, the Governor was back in Sacramento to make his State of the State address to the assembled houses of the Legislature. Prior to Brown’s words, his father, Pat, was introduced, and received a standing ovation. Next, Jerry Brown delivered a 22-minute speech. It received no applause at all.

Brown’s inability to extricate his campaign from isolation has been apparent throughout his six-month struggle, but nowhere was it more clear-cut than in Iowa. For his last swing across the state, the Brown for President campaign chartered a propeller-driven DC-3. The airplane was originally manufactured in 1942, and evokes Immediate flashes of Humphrey Bogart at the airstrip In “Casablanca.

The weather facing this ancient flying machine seems emblematic of the Brown campaign. Blizzard conditions are expected at most of the travel stops.

Jerry Brown himself seems impervious to it all. If the final measure of this would-be President is to be taken from how well he deals with this, the deepest adversity In his career thus far, he passes personally unscathed. As usual, Jerry Brown is wearing no overcoat over his suit and only a blue wool scarf borrowed from a reporter to hold off the cold. Nonetheless, he doesn’t shiver. Instead he seems cheery.

By the time he’s on the ground In Dubuque, chunks of ice are sailing through the air and one of the network reporters does a stand-up with the flying slush and the DC-3 In the background. He reports that “a source” in the Brown campaign has confirmed that things look so bad for 1980 that all thoughts of winning this year have now been abandoned In favor of a strategy pointing to 1984. Other Brown aides deny the Information vehemently.

When Brown returns to the airport, two hours later, there is a 10-minute delay while alcohol is sprayed on the DC-3 strip the ice off its wings. Waiting, Brown talks to aides in California over the pay phone, and conducts state business.

Back in the air on the way to Davenport, the subject of Carter’s complete reversal in the polls is brought up. Brown says he isn’t intimidated by it. “Governing by crisis,” as Jerry Brown calls it, is a dangerous game, he says, and “what goes up comes down the same way.” Carter is going to have to “do something decisive, if he’s going to insist on playing decisive leader much longer.” When that time comes, Brown argues, the hollowness of the “cosmetic” role will show through: “He doesn’t know what’s going on. No more than Kennedy. Neither of them can put it all together. I’II stand or fall on the ideas I’m presenting. Neither of them could say the same thing.”

By 6 P.M., in Davenport, he wins a long ovation before returning to yet another airport over icy streets. Only the last leg to Des Moines remains, and Brown is effusive, almost bubbly. This is a side of Jerry Brown that rarely makes its way into the image. This is the Jerry Brown who is a relatively young man playing in the Big Leagues, immersed In the excitement of it all.

The historical antecedent for this additional piece to the Brown puzzle is the Jerry Brown who after he left the Jesuits and graduated from Yale Law School, and before he began his practice with a prestigious Southern California firm – took an extended vacation at the age of 28, traveling In South America. “Life is so full,” he wrote his parents at the time, “that It seems sacrilegious to squander it away, sunk In an office chair …. The juices are running dry and youth ebbs away and there is a whole planet to see. . .. What strikes me so … is the vastness of things and how they cry out to be explored. The possibilities are limitless. So many styles of life, so many ways of looking at things. … ” This Jerry Brown is on a quest, and seems content with treading water while he waits for history to swell up and sling him forward. In the meantime, he enjoys it too much to stop.

The people who watch him day in and day out take note of this attitude. Two of the press people close to the rear of the DC- 3 are discussing the state of the man’s maturity, as they have for days. “You know,” the first says, “I do believe the man’s mellowing. Linda must be good for him.”

“Don’t write ‘mellow,'” the second advises while looking away at the ice on the windows. “People will think you’re from L.A.”

“Well, isn’t he mellowing?”

At this moment, the DC- 3 is battling gale-force headwinds and cruising toward Des Moines at a ground speed of 87 miles per hour. “He’d better

be,” says the second. “Patience is one of the few options he has left.”

Leave a Reply