New York Times Magazine – June 11, 1978

By 10 A.M. on Friday, July 15, 1977, Robyn Wesley, a midwife specializing in home births, and Kim Myers, a freelance carpenter, had reported to the Superior Court for the County of Santa Clara, State of California, the Honorable John R. Kennedy presiding. Later that day, Robyn and Kim’s 2- year-old daughter would begin dying, but on their way to court, the warm Friday morning bore no hint of approaching death. The sun had already burned the dew off the mountains to the west, and by 10 o’clock the peaks were hidden by the umbrella of smog rising off the interlacing housing tracts of the Santa Clara Valley.

Both Kim and Robyn were defendants in an eviction suit filed by one Alyce Lee Burns against Donald Eldridge, Mark Schneider, Robyn Wesley, and one to 500 additional John Doe squatters residing at 32100 Page Mill Road, Palo Alto, Calif. This property comprised some 750 acres overlooking the suburban community of Palo Alto and neighboring Stanford University, three-quarters of the way up the eastern slope of the Santa Cruz Mountains that run down the spine of the San Francisco Peninsula. At the time of Wesley and Myers’s court appearance, the acreage was occupied by 50 adults and 10 children in 27 dwellings. Like the first homesteaders to migrate to 32100 Page Mill in 1969, all of them felt they had found a place to be gentle, know each other and get back to basics. The settlers had dubbed themselves, their homes and the property “The Land.” After eight years, this “counterculture” was now beginning its last act. Before 1978, The Land would be no more than the 50 people themselves, and they were scattered, and missing a child.

For the last three months, Robyn and Kim had been living apart. The couple’s daughter, Sierra Laurel Wesley Myers, had been shared equally between Kim and Robyn since their breakup. At the age of 2, Sierra walked everywhere by herself in the hillsides around her home, and seemed totally unafraid. Sierra was an especially magical little girl. She had Rubens cheeks and intensely bright blue eyes. Many of her neighbors used to drop by her parents’ cabin just to visit their little girl. During her parents’ day in court, she went with one of her adult friends to the beach at San Gregorio. The eviction of Robyn and her neighbors had already been a long process when trial finally began on July 15. By early afternoon, the judge recessed, and scheduled another hearing for Wednesday, July 20, and adjourned court until then.

Kim Myers and Robyn Wesley had arranged that Kim would meet their daughter Sierra back at the Ranch House after court. He planned to bring her to the big house at Struggle Mountain, a mile down the road from The Land. As part of her midwife practice, Robyn had arranged to meet a couple at one of the Struggle Mountain cottages for a prenatal visit at 6 P.M. When her meeting was over, Robyn and Sierra would go back to their cabin by the walnut orchard on the 750-acre rolling watershed at 32100 Page Mill Road.

1

Sierra Myers met her daddy at the Ranch House around 4:30 Friday afternoon. Kim Myers remembers that Friday as a hot day. Father and daughter played for a bit and then went to Struggle Mountain. For the entire week Kim had been having trouble starting his 1962 Rambler station wagon, and he planned to fix it while Sierra played.

Struggle Mountain is a cluster of four buildings on four and a half acres at 31570 Page Mill Road where friends are welcome for short stays. That day Kim parked his Rambler near the side of the largest house, about 30 feet from the community’s 4-foot-deep circular swimming pool. Sierra began playing in the yard with Soul, Struggle Mountain resident Joanne LeBright’s daughter. Kim popped the hood and opened the Rambler’s carburetor. While he was working, Soul and her mother left, and Sierra went over to the swings near the pool. Kim got behind the Rambler’s steering wheel to start the engine and test his work.

When he did, the carburetor backfired and exploded, momentarily engulfing the engine in flames. Sierra’s father leaped out and began yelling “Fire!” Iris Moore, Winter Sojourner and Brigid McCaw came scrambling out of the big house and Neil Reichline grabbed a fire extinguisher, but the fire was out before he reached the car. Soon, Robyn Wesley appeared on the scene to keep her prenatal appointment and to pick up Sierra. She spoke with Kim briefly about the fire, and then joked about their daughter’s day at the beach.

“Well,” Robyn asked, “did SiSi drown herself today?”

Kim said no, that she’d had a good time, and he smiled behind his moustache. Despite their separation, he and Robyn were still close.

After a little more conversation, Robyn asked where Sierra was. Kim had last seen her right before the fire, and didn’t exactly know. Neither did any of the other people still around the yard. Kim went to look on the downhill slope and Robyn decided to check the cottages. Seconds later, Iris Moore screamed and the sound echoed in the marrow of Robyn’s bones. Kim heard it too and bolted in Iris’s direction.

Iris Moore had found Sierra floating face down in the pool. The child’s skin had a blue tinge and she wasn’t breathing. Iris had just completed an emergency-medicine course.

“Work on her, Iris,” Kim yelled. “Work on her.”

At the top of her voice, Robyn Wesley begged God not to take her baby. While Iris applied mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, a car was brought up and Iris and Sierra got in the back seat. Kim sat in the front next to the driver and they charged down the hill toward the Stanford University Hospital, 12 miles away on the flats. Robyn followed in a second car. Someone at Struggle Mountain called an ambulance and it met the caravan halfway down the grade. Sierra was transferred from the car and hooked to oxygen apparatus immediately. Kim got in the following car with Robyn while the ambulance driver radioed ahead to the emergency room.

At around 6 P.M., Dr. Terence Stull was notified that a Code 3 infant was on the way to the Palo Alto-Stanford University Hospital. Stull was covering Stanford’s pediatrics ward that evening, and he and the senior resident, Keith Kimble, decided they’d better be in emergency to meet it. The infant was brought in with an oxygen mask on her face. She was flaccid and had no heartbeat. Pure oxygen was being forced into her lungs by squeezing the inflatable bag on the side of the mask. The anesthesiologist on duty lifted the emergency rig off Sierra’s face and ran a plastic tube down one nostril and into her trachea. It was attached to an oxygen bag that the anesthesiologist continued to squeeze rhythmically. Adrenalin was shot into the child’s heart, and Stull performed external cardiac massage. Keith Kimble supervised the flow through the intravenous needles inserted in Sierra’s arm.

In essence, drowning is a series of shocks sustained by the body. The biggest of them is the effect of the absence of oxygen on the body tissues. As in all cases of shock, oxygen-starved tissues swell. Brain tissues, unlike most others, are tightly encased in bone. When the brain swells, it immediately begins pushing itself against the surrounding skull. To fight that cerebral swelling, a dosage of Decadron, a steroid, was administered through the tube in the infant’s arm. That was followed by dopamine to raise the blood pressure, calcium salts to stimulate the heart, phenobarbital to prevent seizures, and a form of sodium bicarbonate to reduce the acidity in the blood. Within 10 minutes, a strengthening heartbeat returned, and within 20, her blood pressure and pulse had stabilized somewhere close to normal. The infant was still unconscious, and the bag still breathed for her.

As soon as Sierra stabilized somewhat, the doctors arranged to move her upstairs by elevator to the intensive care ward in Pediatrics. Once life functions have been restored or supported, the treatment for drowning consists of slowing body-action down to reduce swelling. Upstairs, Sierra was laid on a thermal blanket that reduced her temperature to the middle 80’s Fahrenheit. The cold induced shivering as a natural reaction, which in tum used up oxygen that would otherwise be used by the brain to heal itself. To suppress the shivers, the infant was dosed with Pavulon, a derivative of curare, a poison used by South American Indians to paralyze game. A tiny tube was run in her arm, up the vein and into her heart to measure her central venous pressure. It and a regular blood-pressure line were run into a button-covered blue box called the Tektronix 404, which emits a steady succession of electronic bleeps. Sierra’s lung functions had not returned, and could not, as long as she was paralyzed with Pavulon. A respirator did most of Sierra’s breathing for the next eight days.

While all this transpired, the parents waited outside the emergency-room doors. Neither Kim nor Robyn thought it was helpful to bottle up their emotions, and their sobs and crying bothered the other people waiting to see the doctors. They moved outside by themselves, leaving inside the folks from Struggle Mountain, who had raced down the hill and tried to offer comfort. As far as Robyn Wesley was concerned, nothing could have undercut her more than this tragedy. Her daughter had been the springboard for much of what now made up Robyn’s life.

2

Robyn Wesley had been born in suburban Chicago to an upper-middle-class family that eventually migrated to Orlando, Florida. She married straight out of high school and moved with her husband to Savannah, Georgia, in 1969, where they both began selling advertising space for Time Incorporated. At first they were bent on success, working 12 hours a day, six days a week. Robyn and her husband brought in a good income, but after the first year, their enthusiasm for the routine began wearing thin. Her husband had grown his hair long, but had to hide it under a wig whenever they went out of the house. They both enjoyed smoking marijuana, and talked about moving West. Robyn and her husband left for California a few months into 1970.

Robyn Wesley

They went their separate ways soon after reaching the West Coast. Robyn ended up working in San Bernardino with retarded children for a year and a half before moving north to Mountain View, California, to attend junior college. The ambiance of her neighborhood in Mountain View reinforced a lot of her strongest feelings at the time. Almost everyone she knew talked about depending less on the civilization of stucco and machinery around them and taking more responsibility for the basics of their lives. On her Mountain View block, three residents eventually moved to The Land. Robyn finally followed her friend Mary Konczyk there in 1973.

The dominant features of the property at 32100 Page Mill Road are two ridges running in roughly parallel lines across the land from the northwest to the southeast. The area contains the headwaters of the Stevens Creek and a 5-acre cattail bog that is one of the Bay Area’s few natural swamps. The tributaries are lined with heavy thickets of oak, madrone and bay trees. Robyn, Kim and the others lived mostly in these thickets. Their homes were made from recycled lumber, and were sometimes referred to as “shacks” or “squatter dwellings” by the newspapers.

By the time of their 1976 court appearance, the community’s buildings had in fact become relatively sturdy. Eventually, photographs of the structures were run in the local papers, and were looked upon by some as a sort of folk art. Many buildings sported inlays of several shades of hardwood, and had stained-glass windows created by the artisans of The Land.

By the time of their 1976 court appearance, the community’s buildings had in fact become relatively sturdy. Eventually, photographs of the structures were run in the local papers, and were looked upon by some as a sort of folk art. Many buildings sported inlays of several shades of hardwood, and had stained-glass windows created by the artisans of The Land.

The only structures on the property, when Mrs. Burns first purchased it in the early 1950’s, were the original ranch house on Page Mill Road-built before the 1906 earthquake and surrounded by several outbuildings-and a large tin barn. By 1968, the growing university town of Palo Alto had extended its city borders and its utilities district to include the Burns property. At this time, the Bums family took steps to sell. The buyer was one Donald Eldridge, the first party listed in Bums’s 1977 complaint.

Eldridge was a millionaire by virtue of his development of several key color video processes, and Eldridge supported a number of antiwar and community organizing projects through a San Francisco-based personal foundation. His liberal politics and cultural tolerance, combined with the beauty of the eastern Santa Cruz slope, attracted a late 60s migration of young, long-haired refugees from society at large. The vacant structures at 32100 Page Mill Road were occupied by an assortment of young people. Eldridge let them stay on as caretakers, and was later to say that he felt they didn’t mar the natural setting and that their presence protected the place from four wheel-drive vandals. By 1971, the overflow crowd from the ranch house had marched back on the remaining 750 acres and groups had begun homesteading. The new residents did little to disturb the countryside. For the first year they lived in tepees and tents until wooden structures were completed.

Over the years, The Land had become by far the largest grouping of its kind in a neighborhood full of such settlements. The last four miles of upper Page Mill Road east of the crest are populated with clusters of extended families that have names like Struggle Mountain, Rancho Diablo and Earth Ranch. Electricity never spread further than the Ranch House buildings and water for the first backlanders had to be hand-carried from the spring. Later, cold water was brought to the buildings through a series of plastic pipes and hoses connecting a spring box with an outside tap. The new residents eventually named the shorter unnamed ridge behind the barn Sadhana Ridge, after a group called the Sadhana Foundation that came through in 1972. The name was taken from Sanskrit, and refers to the path followed by Hindus in their quest for enlightenment.

Kim Myers, 32, moved to The Land with the original backland settlers in 1971. Robyn Wesley, 26, arrived in early 1973. Their daughter Sierra was born in one of the small cabins behind the Ranch House on the last day of April in 1975. For most of the more than three years they lived together at The Land, Robyn and Kim occupied a cabin below Sadhana Ridge, a mile southwest of the barn. It was next to a walnut orchard gone wild. Their nearest neighbors were across a steep gully and up the slope but they saw them often. Everyone who lived on The Land knew everyone else and spent time together. In 1974, after The Land was found to be in violation of city building codes, the settlers prepared a booklet to explain themselves and to offer alternatives to enforcement of the code. In the preamble of the booklet, The Land was described as “a nonviolent, spiritually minded community …. While the society as a whole seems paralyzed by a deep loss of faith, the life on this land represents … a belief that trust, love and sharing are real forces in the world … ” Originally the internal politics of the community focused on conversation, making music, eating communally and building houses. In recent years, as the community had to deal with outside political forces, The Land meeting-where everyone had to reach a consensus in order for action to be taken–came into common use.

Robyn and Kim began living together a year after she first settled at The Land and one of their first decisions was to have a baby. When Robyn became pregnant, she and Kim were sure about wanting to have their child at home, on The Land. Robyn Wesley considered birth to be both a natural and spiritual process. She wanted to experience it fully, and to do that, she felt she had to have control over its setting. Robyn knew lots of women who had had negative hospital birth experiences, and felt they hadn’t got the support they needed from the hospital environment. With the approval of her obstetrician, Robyn found a midwife who would help her deliver at home.

On the last day of April in 1975, Robyn Wesley spent most of 12 hours of labor walking around and standing up. Kim, the midwife and five other friends were there loving her and cheering her on. When the last wave of contractions started, Robyn Wesley finally lay down on the bed, gave two quick pushes and Sierra Laurel Wesley Myers was born.

Robyn said the whole experience felt like magic, and from that point on, she devoted a great deal of energy to helping other women have the same kind of birth she’d enjoyed. Robyn and two women from Struggle Mountain soon enrolled in a midwifery class in Palo Alto. After completing the three-month course, and backing up her teacher on a few training births, Robyn ran her first delivery. It was on a houseboat in the Redwood City, Calif., yacht harbor.

Robyn built up a practice that took her to as many as five births a month. She charged $100 for each birth and $50 for the couple’s prenatal meetings. Robyn always worked with both a backup midwife and a referring obstetrician. Sierra used to accompany her mother on a lot of the prenatal visits.

3

When Terry Stull found Kim and Robyn where they waited, both parents were in a state of agony and disbelief, but it didn’t keep Robyn from recognizing him. Young Dr. Stull lived with seven other people in a house called La Cresta in Los Altos, and had previously met Robyn when she delivered one of his housemate’s children. Up until that moment, Dr. Stull had no idea who the infant was.

“Is she alive?” Robyn begged.

“She’s alive,” he answered. Dr. Stull went on to explain that she was alive “for now.” Robyn chewed her lip and tried to ignore the terror welling up in her.

Terry led the parents up to Pediatrics, where they established themselves on a couch in the waiting room. One entire wall of the room was papered with a photographic blowup of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Kim and Robyn waited in front of the mural for the next hour and a half while the Intensive Care nurses continued adjusting Sierra’s equipment and further stabilizing her.

When Robyn and Kim finally saw Sierra in the intensive care ward on Friday night, she lay on her back on the cooling pad, covered by a blanket. One green towel had been wrapped around the back of her head and another around the front to support the tubes running into her nose. The wrappings sat on the child’s head like a turban. Robyn choked at the horror of the scene. This couldn’t be happening. Not to her. Her mind battled to try and somehow deny what her eyes saw. That struggle would be the crux of Robyn’s dilemma for the next eight days.

Robyn Wesley wanted to pick her baby up but there were too many tubes, so she stroked her daughter’s leg and talked to her. Robyn tried to tell Sierra what had happened to her and that she would be all right. Sierra made no movement and gave no sign of recognition, but her mother was sure she was hearing inside there somewhere. The room and the hallway outside were full of the steady bleeping of the Tektronix 404. Robyn Wesley quickly understood that the rhythm of the bleeps was Sierra’s body talking, and she constantly tracked the noise with the back of her mind. It was like a lifeline between the two of them.

4

Kim and Robyn never had to maintain their vigil with Sierra alone. Word about the accident had spread throughout The Land within an hour after the cars screeched down the hill to meet the ambulance.

By Saturday afternoon, Stanford’s Pediatrics waiting room had filled up with sleeping bags, back-packs and bunches of wildflowers gathered off Lone Oak Hill. The crowd ebbed and flowed, but there were rarely less than 20 of Sierra’s friends in the ward at any given time. People had come because they loved both Kim and Robyn and wanted to help, but mostly they came to see Sierra. She was thought by everyone to be an extraordinary child.

At least one nurse was always at Sierra’s bedside, monitoring both the infant and the Tektronix 404. The nurses turned Sierra over every half-hour to minimize the damage done to her skin by the intense cold. Often they were assisted by one or another of Sierra’s longhaired friends. Several of them were in the room most of the time. They told her stories and sang her favorite songs. There is no scientific evidence that people in deep comas receive communication, but no one from The Land had any doubts that Sierra did. The Land visitors believed Sierra Myers heard and felt the energy they sent her. The nurses shared The Land visitors’ opinion, and always made it a practice to talk to their unconscious patients.

Despite everyone’s faith, it was at first difficult to believe that Sierra was really there inside the tubed and wired body on the bed. She was so still. But by Saturday, that had changed and everyone agreed that they now felt some of Sierra in her body and in the surrounding room. These feelings were interpreted as a hopeful sign and grasped at by some as the first signal of Sierra’s resurgence. Robyn Wesley remained doubtful. That wasn’t Robyn’s Sierra lying there. She wanted to know where the rest of her daughter was.

Ignorance about the geography around the borders of death was widespread among the visitors to Pediatrics, and those in The Land vigil quickly took steps to correct it. Over the next few days, at virtually all hours of any day, someone was studying Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s “On Death And Dying,” or Dr. Raymond A. Moody Jr.’s “Life After Life.” Both Drs. Kübler-Ross and Moody have examined death by studying the accounts of those who had been pronounced dead and who had then been revived. In those books, the people who “came back” reported that though it may be preceded by great pain, death is not in itself a painful process : It is a sensation of incredible and overwhelming peace. Some of those who had been revived reported being greeted in death by people whom they were close with, people who had died before them. Dr. Kübler-Ross does write of one 2-year-old child of fundamentalist Christians who said he was met by Jesus while in a coma. Dr. Kübler-Ross is sure children are welcomed to death by an affirmative presence.

That knowledge soothed Robyn. After her first weekend in Pediatrics, Robyn was sure her daughter would be in a good place even if she didn’t come back, but that didn’t make it any easier. Robyn did not want to live without Sierra. It wasn’t right that her daughter should go off to death so fragile and small. Robyn both wanted and refused to accept the possibility of death, until she reached a state of total exhaustion Sunday morning. She and Kim finally curled up for their first sleep in the interns’ room down the hall.

Robyn Wesley and Kim Myers awoke 20 minutes later when Maryann Konczyk shook Robyn’s arm.

“Something’s happening to Sierra,” Maryann said.

Robyn and Kim were running down the hallway in an instant. The Tektronix 404’s bleep had changed to ringing bells. Eight doctors and nurses were surrounding the bed and working furiously on the child’s body. Sierra’s heart had stopped.

Kim and Robyn took a space at the corner of the bed and beseeched the universe to let their daughter live. In a matter of seconds, the bells stopped ringing and the Tektronix 404’s bleep returned, steady and strong. Deep down, Robyn knew the reprieve was just temporary.

She and Kim were sobbing and holding each other, there by Sierra’s bed. “What if we’re holding her back, Kimmer?” Robyn asked. “What if she needs to die and we’re not letting her?”

When the crowd cleared out of the room as Sierra once again stabilized, Robyn Wesley told her daughter in a whispering voice close to her ear that it was all right if she had to die. Robyn said she would understand, but inside herself she knew it wasn’t altogether true.

For Kim Myers, the seizure marked a new level of reality. Before, he had been sure she would just wake up and be Sierra again, and everything would be all right. But now, SiSi was so close to being gone that Kim shivered. Over the next 24 hours, his mind kept spontaneously remembering bits and pieces of dreams he had had about dying throughout his life.

5

Kim Myers reached The Land via the United States Army. Drafted soon after graduating from California State University, Long Beach, with a B.A. in English in 1968, Myers spent ’69 and ’70 with the 24th Medical Battalion, first in Kansas and then in Germany. Myers hated the Army. The only thing good that ever happened to him there was when a friend showed him one of the first copies of “The Whole Earth Catalogue.” Its creed of simple living, peace and reconciliation with nature was everything Private Myers wanted. After his discharge, he showed up on the San Francisco Peninsula looking for a place to live off his Army unemployment benefits and grow a garden.

Kim Myers reached The Land via the United States Army. Drafted soon after graduating from California State University, Long Beach, with a B.A. in English in 1968, Myers spent ’69 and ’70 with the 24th Medical Battalion, first in Kansas and then in Germany. Myers hated the Army. The only thing good that ever happened to him there was when a friend showed him one of the first copies of “The Whole Earth Catalogue.” Its creed of simple living, peace and reconciliation with nature was everything Private Myers wanted. After his discharge, he showed up on the San Francisco Peninsula looking for a place to live off his Army unemployment benefits and grow a garden.

The place he found was a shack below the garage at Rancho Diablo, a cluster of buildings three miles from 32100 Page Mill Road on Skyline Boulevard. The commune there was in the process of breaking up. Stewart Brand – who is now California Governor Jerry Brown’s appropriate-technology adviser – was at that time in the garage, finishing “The Last Whole Earth Catalogue.” Kim eventually joined a fragment of Rancho Diablo’s commune in looking for another place to live in the depths of Donald Eldridge’s holdings at 32100 Page Mill Road.

In 1971, a group of approximately 20 settlers, with Kim Myers among them, moved back along the watershed and spread out in tepees under the trees. Kim began to feel a common mind growing among the settlers. Hooked into that shared feeling, Kim felt elevated. Everything seemed cleaner and more real. During the slow July days, he read “Autobiography of a Yogi” by Paramahansa Yogananda, and learned carpentry.

Kim Myers

The settlers lived poor and needed little cash to survive. What they had was shared. The Land community grew and shrank and stabilized during those first years. Kim Myers lived in both the back and the front of The Land, and saw people come and go. He was at The Land when overcrowding fragmented the backlands settlers during the second summer, and led to a second deeper migration toward Black Mountain. He was still there the next summer when the police helicopters began buzzing Sadhana Ridge to keep the squatters from lying out there in various stages of nakedness. The summer after that, Kim began living with Robyn.

From the first it marked a new kind of commitment for Kim. He had decided to become a family man and took the responsibility seriously. He remodeled the middle cottage, in a row of three one-room buildings behind the old Ranch House, so Robyn could have the nicest possible pregnancy and birth. Kim and Robyn’s move to the front portion of Eldridge’s property proved to be an important event in the history of the squatter community. Until that time, the front settlers and the backlands folk had thought of themselves as two separate groupings. The presence of the backland couple behind the Ranch House who were expecting a baby gave those at the front of the land a new perspective and brought the community together. At about the same time, a settler named Mark Schneider began serving breakfasts for everyone in the Long Hall beyond the front cottages. This sealed the reunion and created a Land ritual at the same time.

The Long Hall had originally been constructed by one Louis O’Neal, who was the owner of 32100 Page Mill from the turn of the century until his death in 1942. O’Neal was a leader in the Republican party, and designed the building for rural caucuses and rallies. Legend had it that several California governors were first anointed there. Those of The Land used it as a general catchall gathering place. Breakfast was served regularly every morning to the 35 or so people who had to drive down the hill to work. On Sunday mornings, folks came for breakfast from up and down Page Hill Road and also from The Land. The institution of the Sunday breakfasts proved to be the final step in merging the groups on The Land into a single entity.

The Long Hall had originally been constructed by one Louis O’Neal, who was the owner of 32100 Page Mill from the turn of the century until his death in 1942. O’Neal was a leader in the Republican party, and designed the building for rural caucuses and rallies. Legend had it that several California governors were first anointed there. Those of The Land used it as a general catchall gathering place. Breakfast was served regularly every morning to the 35 or so people who had to drive down the hill to work. On Sunday mornings, folks came for breakfast from up and down Page Hill Road and also from The Land. The institution of the Sunday breakfasts proved to be the final step in merging the groups on The Land into a single entity.

When Sierra was born, it seemed from the beginning that she was the special child of that convergence of energy. She and her parents stayed in the front cottage for her first year, and then moved into the cabin by the walnut orchard.

Sierra thrived there and became the centerpiece of Kim Myers’s life. He wanted to nurture her, and was amazed at how much she nurtured him back. As only children can, she loved without reservation. Kim will always remember his daughter as she was when she’d run up to him to ask what he was up to. “What doin’, Daddy?” she used to ask. “Whatdoin’ ?”

On Sunday, July 17, on her back in the Intensive Care ward, Sierra Laurel Wesley Myers asked nothing at all. She remained unconscious and the Tektronix 404 bleeped steadily through the night.

6

On Monday, July 18, the routine at the hospital changed. With the influx of regular weekly visitors, the ward staff shifted The Land’s presence to make room. Several portable beds were set up on the patio outside Sierra’s window, and the supplies and parcels in the waiting room were stowed under the couches. The changes were explained to the group at a morning briefing that became a daily feature for the rest of Sierra’s hospital stay. The doctors in charge of relations with the patient’s family and friends were Terry Stull and Frederick Lloyd.

Rick Lloyd was Sierra’s personal physician. He and his wife had returned from vacation on Sunday to find a message that Sierra was in the hospital. He rushed over, and from then on he was a regular participant in her care. Lloyd was a pediatrician to a lot of The Land’s babies. At the time he first encountered the mountain community, a number of local pediatricians refused to accept home-birth babies as patients because they had been the recipients of “less than optimal care.” Lloyd disagreed with the rationale. Sierra began coming to him for all the standard childhood reasons, and proved to be a remarkably healthy child.

At the first briefing, Stull and Lloyd tried to summarize the medical situation. There were three major factors that worked against Sierra’s recovery. The first was that she had probably been immersed in the pool for longer than five minutes. Children’s brains can sustain lack of oxygen longer than those of adults, but after five minutes, that advantage is lost. The second problem was that she could not be cooled until her arrival in the emergency room; the cerebral swelling had had a long time to develop. The last difficulty was that she had arrived at the hospital in a state of complete heart arrest.

Soon they would begin to take her off Pavulon, to bring her temperature back to normal. At that point, they would measure the electrical activity in her brain with an electroencephalogram. The measurements would give them a broad picture of how much brain was still functioning inside her skull.

The Land community believed that Sierra had a spiritual consciousness, independent of her brain, that was fully operative. Aside from observing and cooperating with the routine in the ward, all their attempts to participate in her care were aimed at making contact with that consciousness. They engaged in common meditation to send their healing vibrations to Sierra. On the wall of the waiting room, drawings and words of encouragement were posted for the benefit of those who could only sit and wait. The vigil was exhausting for everyone. Neil Reichline left the hospital Monday afternoon to go home and try to rest after staying up all night talking with Robyn, but he couldn’t sleep. The bird outside his window sounded like a Tektronix 404.

Robyn felt ravaged most of the time. She struggled to keep her feelings from just giving up and shutting down. She wanted to experience whatever was going on as fully as she could. She had to work on herself to keep open, so she could try to understand and make sense of things. Robyn never went out of reach of the sound of Sierra’s Tektronix 404, and sometimes borrowed someone’s child to hold, since she couldn’t hold her own. Robyn desperately wanted her daughter to live, but she didn’t want to keep Sierra back from what Sierra needed to do, even if it was to die. She asked her friend Neil Reichline to counsel with her and they spent hours talking and trying to expose and understand the demons that danced in her mind.

The technique she and Neil used was called “co-counseling,” a method that a good number of those on The Land had learned, and regularly practiced. The premise of co-counseling is that people limit their clarity and creativity by shutting their emotions off, and keeping a stiff upper lip. Co-counseling seeks to bring the emotions to the surface and allow them to discharge themselves. Crying, shaking, yawning and laughing are all sought out as the natural physical mechanisms for emotional discharge. Neil and Robyn regularly holed up in the interns’ sleeping room, and went through them all.

Neil Reichline

On Monday night, Robyn felt as desperate as she’d ever felt. Neil asked her if there was something more he could do, and Robyn said she wanted to talk to Baba Ram Dass. Although they had never met, Robyn considered Baba Ram Dass to be her teacher, and had read all his books. Ram Dass first won notoriety as Richard Alpert, Timothy Leary’s partner in the initial experiments with LSD at Harvard University. Alpert then went on to India in search of spiritual understanding, returned with the name Baba Ram Dass and became a religious visionary and mystic. With the help of mutual friends, Neil finally reached Baba Ram Dass at a house in Massachusetts at 2 A.M. Eastern Standard Time. Ram Dass made no complaint at the hour, and asked to talk with Robyn after Reichline explained the situation.

He told Robyn that she and Kim were “walking through the hottest fire .” Robyn cried to him about how hard it was to be in Sierra’s room, how helpless she felt. Ram Dass said she should go in the room and just look at what was really happening. She shouldn’t resist it and she shouldn’t want it to be different. She had to flow and float.

But what about her panic? Robyn demanded. It was driving her crazy.

Ram Dass said she should just experience it as well. When it felt holy, let it be holy, and when it felt scary, let it be scary. In recognizing that her panic existed, she would also recognize that parts of her that were not in panic also existed; that perspective would put the panic in its proper place. Robyn felt peace exuding from her teacher, even as they spoke on the phone. She finally slept again on Monday night, feeling more on top of things than she had in a while.

On the next day, Tuesday, July 19, her equanimity was destroyed by a twitch. The twitch was a tremor that ran down one of Sierra’s legs. Robyn was sitting beside her daughter and saw it. It was the first movement the infant had made in four days. The doctors were very cautious about its possible meaning. Even so, it made the little girl seem suddenly alive. Kim began telling Robyn stories about how they would all live in their cabin again, and make the best of whatever Sierra had left, but Robyn didn’t believe it. She had worked with damaged children and had seen parents pour out love and concern for children who could never even know the parents were there.

The chief topic for discussion around the waiting room Tuesday evening was what it would be like if Sierra lived. On the edges of that discussion, a few people talked about the case in court. The following morning, The Land was due back in front of the Honorable John R. Kennedy.

Baba Ram Dass

7

The 44 defendants in Superior Court actually knew relatively little about Mrs. Alyce Lee Burns, the plaintiff. They had read in a local weekly that she was from Watsonville, California, and that her husband, Emmet Bums, had been suspended from the practice of law in the late 50’s for co-mingling his clients’ funds with his own, and that he had eventually been disbarred.

Mrs. Bums had re-entered the picture in 1974, when she and Donald Eldridge disagreed over the terms of their payment contract; a series of lawsuits ensued, some of which are still undecided. In the meantime, Mrs. Burns held a foreclosure sale on the untitled holdings at 32100 Page Mill, bought them back and began looking to sell the property again. In January of 1977, Mrs. Burns entered into a series of conversations with the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District (M.R.0.S.D.). In March of 1977, negotiators for Mrs. Bums and the M.R.O.S.D. agreed to exchange 32100 Page Mill Road for $2.1 million. The vacant land would eventually become a cornerstone of the new Montebello Open Space Preserve. Eviction of the occupants was specified as a precondition to closing escrow.

On Wednesday morning, July 20, the defendants’ first step was to explain to the judge why Robyn Wesley and Kim Myers were not present. He immediately severed them from the trial proceedings. Mark Schneider followed that explanation with a request that the entire trial be postponed at least until the following Monday, when the defendants would have a better idea of Sierra’s fate. Everyone, he explained, was tied closely to the fate of the young child; Schneider offered a letter from Drs. Stull and Lloyd attesting that the presence of the larger support group played an important part in sustaining both the patient and her parents. After hearing vehement objections from Burns’s lawyers, Judge Kennedy denied the request and ordered the defense to proceed.

On Wednesday morning, July 20, the defendants’ first step was to explain to the judge why Robyn Wesley and Kim Myers were not present. He immediately severed them from the trial proceedings. Mark Schneider followed that explanation with a request that the entire trial be postponed at least until the following Monday, when the defendants would have a better idea of Sierra’s fate. Everyone, he explained, was tied closely to the fate of the young child; Schneider offered a letter from Drs. Stull and Lloyd attesting that the presence of the larger support group played an important part in sustaining both the patient and her parents. After hearing vehement objections from Burns’s lawyers, Judge Kennedy denied the request and ordered the defense to proceed.

The Land’s case revolved around three arguments. The first was that Mrs. Burns did not have a clear claim to title. The lawyers argued that her original deal with Eldridge had specified that, for every $3,000, Mrs. Burns would exchange title to one acre. Title to 151 acres had been transferred with Eldridge’s down payment; the lawyers argued that Eldridge had finally stopped paying when Mrs. Burns refused to release any more titles, despite several years worth of substantial payments. As long as the title was questionable, The Land community’s lawyers argued, Mrs. Burns had no standing to evict. the second argument was that Mrs. Burns came to court with “unclean hands.” The Land settlers claimed that, in September 1976, members of the Bums family sabotaged The Land’s water system, and that this violated the California law prohibiting turning off utilities to accomplish eviction. Lastly, Mrs. Bums had already entered into an agreement with the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District. California law also provides that if a public agency causes the removal of people from their homes, that agency must relocate them in similar surroundings at its own expense.

Judge Kennedy listened to The Land’s arguments and ruled that none of them was admissible in the trial. The defendants’ lawyers would only be allowed to argue about whether the eviction notice was properly posted, and about how much damages ought to be. The defendants requested a trial by jury, but the judge pointed out that in civil jury trials, the defendants must assume jury costs, and post a bond 10 days before trial. The defense then requested a pauper’s jury, a legal provision where indigent defendants’ jury expenses are assumed by the county. The judge responded that he would rule on the request after each defendant filed an individual financial statement the following morning, and adjourned court for the day.

The next morning, the defense informed Judge Kennedy that only nine defendants had managed to get their financial forms filled out. Those nine, the judge ruled, would be severed from the case along with Kim and Robyn while he considered their applications. The other 33 would stand trial immediately after a recess for lunch. The suddenness of this ruling stunned the defense. The lawyers proceeded to do their best, but could only make a case by trying to squeeze in information by lengthy and exhaustive cross-examination of Mrs. Bums’s witnesses.

The next morning, the defense informed Judge Kennedy that only nine defendants had managed to get their financial forms filled out. Those nine, the judge ruled, would be severed from the case along with Kim and Robyn while he considered their applications. The other 33 would stand trial immediately after a recess for lunch. The suddenness of this ruling stunned the defense. The lawyers proceeded to do their best, but could only make a case by trying to squeeze in information by lengthy and exhaustive cross-examination of Mrs. Bums’s witnesses.

8

By Thursday evening, July 21, troublesome signs had also developed at the hospital. The respirator pressure had had to be increased. The initial chest X-rays, taken at the time of Sierra’s admittance, showed what were called “fluffy infiltrates” in her lower lung. Those deposits of water were slowly causing a condition of chemical pneumonia. On the bed, covered with towels and tubes, Sierra looked to Robyn like she must be hurting intensely.

That vision of her daughter’s suffering pitched Robyn Wesley into the worst anxiety of her life. She was seized with an absolute terror of her daughter’s death that only deepened as Thursday night wore on. She felt cheated and misused, and raged at God to show Himself and justify her pain. At the bottom of her descent, Robyn Wesley called Baba Ram Das again.

“I can’t find God anywhere, Ram Dass,” she sobbed into the hospital’s pay phone.

Baba Ram Dass told her that there was nowhere to look. Before Robyn had a chance to respond he asked her to breathe with him. Just let go for a moment, he said, and do no more than breathe. With each exhalation she should try to release a little fear, with each inhalation, ingest a little love. Robyn Wesley and her teacher breathed together for 10 minutes over the static of their long-distance connection. The rhythm of the exercise let Robyn step away from her awful indecision, and steady herself. After a while, Robyn felt lighter and able to float on the crest of her grief. She felt calm and she felt a deeper sadness than she had ever known, a sadness that was so total it humbled her and mad things seem clear. Whatever was meant to happen would happen. If mother and daughter were separated, it would be as part of a large wholeness that would connect them forever.

The next morning, Friday, July 22, started out looking like the answer to everyone’s prayers. Early in the day, Sierra began making spontaneous efforts to breathe, independent of the respirator, while another series of tremors ran through her legs and feet. The infant seemed to be coming alive, but the doctors cautioned that this was momentary. In several hours, they would have the EEG results, and would know a lot more then.

Eventually, Drs. Terry Stull and Rick Lloyd asked the parents to come with them into the office. Robyn knew the request for privacy meant bad news. The EEG results were disastrous. They indicated a condition termed “diffuse slowing with several secondary runs of suppression” marked by a “preponderance of delta waves” in the brain. The presence of excessive delta waves meant that the brain was operating very poorly. Obviously there was extensive damage from lack of oxygen. The only part of the child’s brain that the doctors were sure was still functioning was the stem of the brain itself. On the evolutionary ladder, a brain stem is the mental equipment of a salamander. Sierra Laurel Wesley Myers, as Kim and Robyn knew her, would never exist again.

Kim Myers and Robyn Wesley sobbed and talked more with the doctors. Stull and Lloyd had doubts whether Sierra would live at all, but it was clear to them that there was little chance she would survive without the constant support of the respirator. The doctors were crying too. They said Sierra seemed to be sinking, even with the equipment. Her vital signs were steadily weakening. It was finally decided between them that if Sierra Myers should go into arrest again, they would accept it as what was meant to be, and make no attempt to revive her. When the news was passed on to the rest of The Land group, it produced what, for a moment, was an overwhelming tide of grief. A lot of people just sat and stared.

By Saturday morning, July 23, the Pediatrics ward felt unbearably claustrophobic to Kim and Robyn. They had to get outside; they left by the stairs. At the plaza outside the hospital’s main entrance, several groups of gypsies were clustered talking to one another. Stanford Hospital is a medical stopping place for a number of West Coast gypsy clans, and the sight was not unusual. Tears were rolling down Kim and Robyn’s faces, and they headed for an oak tree in the middle of a large open field of dry grass behind the hospital. In back of the tree they could see the Santa Cruz Mountains lined up against the sky and they could see the brown folds of their home. Standing alone in the middle of the field they yelled and yelled. The sounds welled up from a bottomless pit of grief trapped inside them. They bellowed their anger at the universe for robbing them of what they had made themselves. They raged and threw fists of

dirt scattering across the dust. Kim found an old rotted fence post and splintered it against the tree. Slowly the wave of rage passed and they sat in the shade sobbing. They said goodbye to their daughter over and over and over again. Finally, they felt cleansed and accepting. Robyn knew she was ready to let Sierra die. She and Kim walked back inside. They were still crying.

At the entrance plaza, the couple passed an old gypsy woman with gold coins arrayed on her breast. She noticed their tears.

“What’s the matter?” she asked.

“Our little daughter is dying,” Robyn answered.

“It’s all right,” the gypsy woman advised. “You are young and you will have many more daughters.”

9

Through the rest of the day, Sierra continued to sink. By 10 P.M. Saturday, the only people left besides the staff were Kim, Robyn, Neil Reichline, Norma Shapiro, Kim’s brother David, Diane Carter, Maryann Konczyk and Mark Schneider. They were all squatting in the hallway and Robyn had just finished telling the others the story of their encounter with the gypsy woman on the entrance plaza. Everyone there remembers feeling a common acceptance of Sierra’s eventual passage into death. After battling through the turmoil of accepting the unacceptable, all of them felt a diffuse kind of joy that even brought an occasional smile. Their gathering was interrupted by the story of their encounter with the gypsy woman on the entrance plaza. Everyone there remembers feeling a common acceptance of Sierra’s eventual passage into death. After battling through the turmoil of accepting the unacceptable, all of them felt a diffuse kind of joy that even brought an occasional smile. Their gathering was interrupted by the woman resident on the evening shift. The resident said another crisis was coming and the group had better come in and say goodbye to Sierra. She didn’t have much time left. The resident was trembling.

Those in the hallway went into Intensive Care and made a circle around the infant’s bed with the two residents and two nurses. They held hands and spoke to the unconscious child in soft and gentle voices. The staff people were sobbing along with the others. Robyn wanted to pick Sierra up, but the tubes were still in place.

Inside her head, Robyn talked with Sierra and told her that she was going to be all right. Her mommy knew she would be. Sierra answered and told her mommy that she knew that mommy and daddy would be all right too.

For five minutes, Sierra’s heart beat slower and slower, but didn’t stop. Something seemed to be holding her in her body by the slimmest of threads.

“What is it, SiSi?” Robyn agonized. “What are you waiting for?”

Robyn thought it might be the window. Her daughter needed the window open. She turned to lift it and when her eyes crossed Kim’s, Robyn suddenly knew Sierra had died. Back on the table, the infant’s heart had finally given up. It was 10:33 P.M. and everyone was crying. Heart failure was the official cause of death, but to those present, it was simply a question of her time having come. Sierra Laurel Wesley Myers had finished what she had come among them to do. Finally, when they all left Intensive Care, Robyn went to the waiting room, held onto Norma Shapiro and shook with sobs. The bleeping had stopped. The hallway seemed strangely empty without the sound of the Tektronix 404.

That night, Kim and Robyn stayed with friends who lived a mile from the hospital Koban, the priest at the nearby Los Altos Buddhist Zendo, came and sat with them. The priest arranged to take Sierra’s ashes after cremation and hold them for the traditional 40-day waiting period before Buddhist burial services.

10

On Aug. 5, 1977, Judge Kennedy issued a memorandum decision on the case of the first 33 defendants in Burns v. Eldridge, Schnieder, Wesley, et al. The judge found against them and they were assessed $1,400 in damages. In his decision, the judge announced that the other 11 defendants would only be allowed to speak to the issue of the level of damages, and nothing else, in their upcoming trial. The 11 recognized the inevitable, allowed their case to be subsumed under the first decision and never went to court again. The Land’s lawyers figured they could stall off the final eviction for a couple of months more, and began filing for a series of technical restraining orders.

On the first day of September 1977, Sierra Laurel Wesley Myers was buried. The service was performed by the priest Koban on the side of Sadhana Ridge. Kohan stood behind a low table topped with a charcoal brazier and an urn of ashes. The words he spoke were all in Japanese, a language no one at The Land understood, but the peace and vision of Koban were discernible in the sound of his voice alone. When he finished speaking, each person present filed by the table and dropped a pinch of incense on the hot charcoal. Kim Myers, Robyn Wesley and the priest carried Sierra’s ashes to her grave. Kim had dug the hole himself earlier in the day. It was on top of a little mound that poked up on the side of the ridge overlooking the walnut orchard and their house. After the urn was laid in the bottom, Kim and Robyn used their hands to fill the grave and sat staring for long moments before they packed down the final handfuls of earth.

On October 20, 1977, deputy sheriffs arrived at The Land and oversaw the final emptying of all the buildings. Throughout their ordeal, Kim and Robyn. had tried to be very clear with each other that their mutual support during the death of their daughter did not mean that they would resume their relationship as it had been before. After the evacuation of 32100 Page Mill, they went their separate ways.

Robyn Wesley moved deeper south in the Santa Cruz Mountains, where she now lives with several other refugees from The Land. Her sense of herself has slowly rebuilt since the death. Some days she still feels SiSi is right there in the room with her, and some days she shivers uncontrollably at the fear Sierra’s absence still inspires.

Kim Myers moved to a house in Mountain View, but felt restless. Since the magic summer of 1974, when he first moved in with Robyn and made Sierra, he had lost most of what was his life. Before the year was out, Kim Myers finally left for a meditation center in northern New Mexico, where he hoped to get a better grip on the life ahead of him.

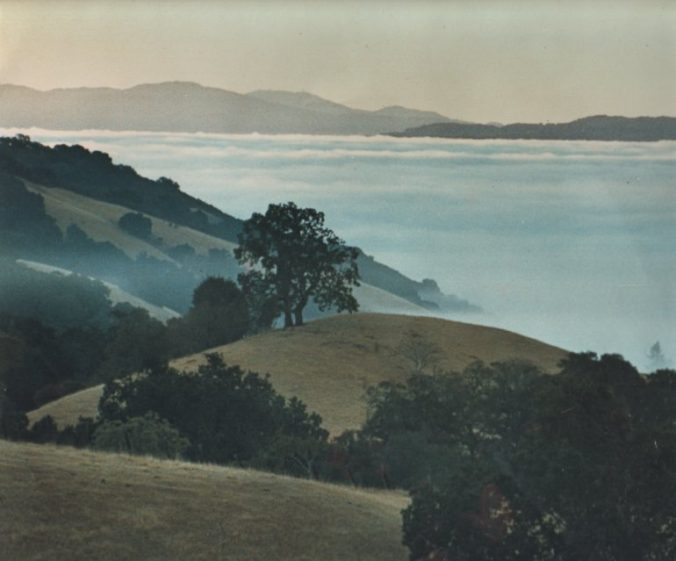

Photo taken in the final hours of the Land

The rest of those on The Land spread in various directions, mostly out to the surrounding hills. Several groups found houses on the Santa Cruz crest. There, they now pay rent and dream of finding another place like the last one. During the remainder of October and November, a number of The Land’s ex-residents occasionally visited their former homes. Slowly they began dismantling the structures in order to save the lumber for other attempts elsewhere. On the morning of December 1, the day before 32100 Page Mill’s title passed to the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District, approximately 15 former residents were on the backlands, patiently stripping their former homes, when the inevitable final act in their drama played itself out.

Within the space of 10 minutes, the Burnses, their lawyer, several members of the M.R.O.S.D. staff and board of directors, and eight Palo Alto police arrived on the scene. The district officials had brought two bulldozers with them. The caravan of once and future owners moved along the backlands, stopping under trees and reducing the home-made houses to splinters one by one. The remnants of those on The Land walked along and watched without incident until the dozer reached a structure known as “Murph’s House.” Murph’s house was still being occupied by Daniel Steinhagen, Phyllis Keisler, and their young son Simon. Their cabin had never been served in the eviction, and the residents claimed it was in fact on the 151 acres to which Eldridge still had clear title. Burns’s lawyer produced a map drawn by the M.R.0 .S.D. staff that showed Murph’s House on the district side of the line. No actual surveying of the boundary had been done in years. When Burns’s lawyer ordered the bulldozer to proceed, Daniel got on the roof and refused to move. Burns’s lawyer summoned the Palo Alto police and three officers went up to get Steinhagen. Daniel went limp and the officers had to carry him off the roof and 500 yards up the hill to their waiting squad car.

When the police returned to Murph’s House, four more people, Edward Delatmne, David McConnell, William Wheatley and Sarah Edgecome, had occupied the roof. Edgecome came down by herself but the others had to be carried away while the bulldozer demolished Murph’s House.

Before the day was out, the devastation was virtually complete. On the frontlands only a garage next to the Long Hall and the three vacant cottages had been saved. Everything else, including the barn, was leveled. The Open Space District planned to use the remaining buildings to store district equipment or to house a caretaker’s office. In the backlands, only two structures were still standing. These were reprieved at the insistence of one Open Space District board member, who argued that the district ought to do a study of the feasibility of preserving them permanently as unoccupied architectural monuments to the “spirit” of The Land.

On Saturday, Dec. 10, sometime around 3:30 A.M., an unknown person or persons entered the Open Space District property at 32100 Page Mill Road and set fires in five of the six remaining buildings. All five buildings were destroyed. Santa Clara County fire marshals were unable to find any suspects in their subsequent investigation. The only remaining structure, one of the cottages behind the old ranch house, may be used to store equipment or may be demolished, but no one will ever live in it again. The only permanent resident of the new Montebello Open Space Preserve will always be Sierra Laurel Wesley Myers, there in the crust of Sadhana Ridge, looking over the walnut orchard toward the thicket where her mommy and daddy’s house once stood.

Sierra Laurel Wesley Myers

1975-1977

David Harris at The Land reunion – 2013

It is a fabulously well-done article from David who captured the zeitgeist of the age, not an easy thing to do.

Also, just a note to say that most (almost all) of the pictures were obtained from the Land wikisite (https://thelandonline.mywikis.wiki/wiki/Home) under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/legalcode). The creators/takers of these photographs are all identified there.