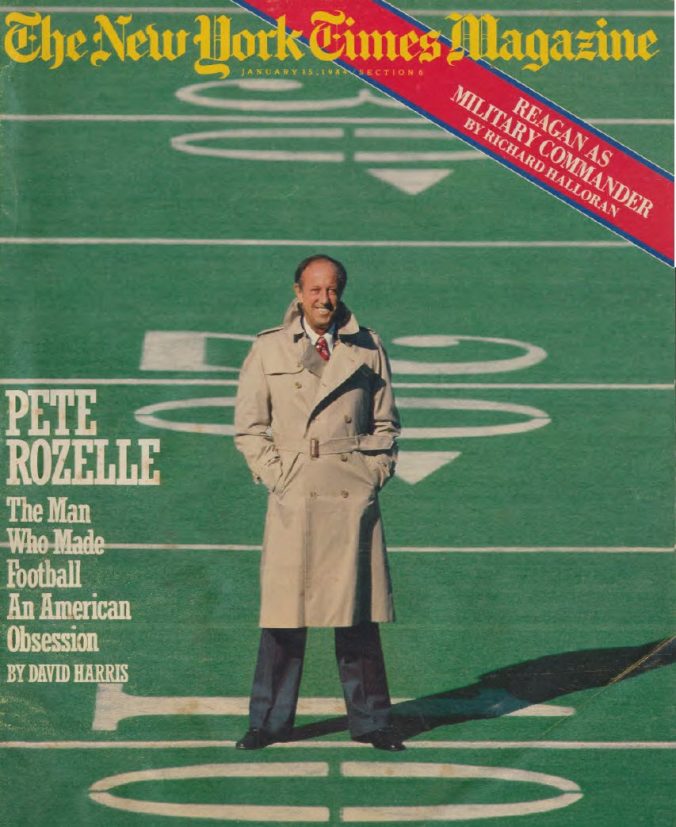

New York Times Magazine – January 15, 1984

Pete Rozelle, commissioner of the National Football League, first encountered the essential premise of his career when he was 10 years old and attending a summer day camp in the hills near his home in southern California. The campers had gathered for “a little talk” by one of the counselors. “Character,” the counselor pointed out, “is what you are. Reputation is what people think you are. But,” he went on as young Rozelle listened intently, “if your reputation is bad, you might as well have bad character – the one is useless without the other.” Pete Rozelle has lived that message ever since. As recently as last April, he cited the summer-camp dictum in conversations with Leonard Tose, the trucking magnate who owns the Philadelphia Eagles. At the time, Tose had reportedly accumulated more than $2 million worth of gambling debts in an Atlantic City casino, and reporters were sniffing around the story. “I talked with Leonard about it,” Rozelle admits. “While casino gambling is perfectly legal, I said to him, when it reaches the point where this could be embarrassing to you or to the club, then it becomes a different problem. Your reputation is valuable. You might as well have a character weakness if people think you do. Leonard tended to agree with me.”

A lot of people tend to agree with Rozelle, and his capacity to extract such agreement has been a key element in his 24-year transformation of the N.F.L. into America’s reigning obsession. He has imprinted his own character on the game he oversees, an accomplishment no other commissioner of any other sport can claim. Whether that will continue is another question altogether. The 1983 season was a disappointment in both stadium attendance and television ratings – the second such disappointing season in a row. Drug scandals and a costly strike have, despite Rozelle’s best efforts, significantly undercut both the game’s reputation and character. A string of lost lawsuits, including one case still on appeal, has damaged the order Rozelle brought to the league and left it in what he calls “serious jeopardy.” Whether the game will continue to be a growth industry remains to be seen.

Next Sunday, Super Bowl Sunday, it will be easy to forget there is indeed a serious and troubled business behind all the flash and anticipation of the contest: Mania will infect at least two major metropolitan areas, those of the two finalists, and, for a solid week, the action will be televised to the rest of the nation in great detail and from every possible angle. Millions of dollars will be wagered on the outcome with bookies in every nook and cranny of America, and the country will choose up sides. For a week, the game pitting 22 men on a 100-yard-long field will apparently matter more to us than anything else on the planet. The business behind that obsession, the National Football League, is an unincorporated not-for-profit association of 28 separate ownerships, which field teams and produce and stage football games for profit. Rozelle, as commissioner and chief executive officer, is the most important person in the business.

For most Americans, engaged in a five-day-a-week struggle both confused and mundane, the battles produced by Rozelle’s N.F.L. seem clear and occasionally noble: 11 men against 11 men, evenly matched between discernible boundaries, each side bound by the same rules, each side with a visible goal to reach and a great prize to gain. Extremely large, agile and well-armored athletes deliver blows and collide with abandon at high speed, and then, for the television audience, they do it all over again in slow-motion instant replay. The game proceeds in short bursts of synchronized combat broken by pauses to regroup. At each break, the stakes escalate. The strategy is enormously complex and the execution brutally simple. The object is to dominate. The experience, for the viewers, is televised adrenalin. More Americans will watch next Sunday’s game than attend church. Most of them will recognize the name Rozelle.

Though the techniques of playing football have evolved through the contributions of hundreds, even thousands, of coaches and players, the national obsession with watching it is the acknowledged accomplishment of Pete Rozelle more than anyone else in the business. In 1960, he was hired to administer a league that had 12 teams. Under his direction, it has grown to 28 and sells 10 million more tickets a year than it did 24 years ago. When Rozelle took office, an average N.F.L. franchise was worth $2 million and the league headquarters were in the back room of a suburban Pennsylvania bank. Today, an average franchise is worth close to $40 million and the commissioner and his staff are ensconced on two floors overlooking Park Avenue in Manhattan.

In 1962, the first television contract Rozelle negotiated sold CBS the rights to televise a single season for $4.6 million. In 1982, Rozelle negotiated contracts that sold those same rights to all three networks for $400 million. Of television’s 10 most-viewed sports events of all time, all 10 are games staged by Rozelle’s league. To describe him as simply a “sports commissioner” is an understatement. Despite a minimum of personal fanfare and a seeming reluctance to publicize himself, Pete Rozelle is the architect of the greatest success story in the modern American entertainment industry.

Before Rozelle, football was more popular in its college form than its professional. Rozelle inherited a muddy, mildly popular game played mostly in ancient industrial-belt stadiums and televised sporadically in black and white. He shaped it into a national addiction fought in sleek new football palaces on a surface like a billiard table and televised in full color every Sunday everywhere.

Rozelle perceived the need of Americans to identify with ritualized physical confrontation, and he understood the terms under which such identification could be maximized. He structured the business of staging such confrontations so that any N.F.L. team stood a chance of beating any other and then marketed that chance with a sure touch. He made his product almost universally available by selling it to the television networks and, by arranging the playing of the game for the widest and most immediate viewer gratification, he made it easy and exciting for everyone to become a fan. By demonstrating personally what seemed appropriate virtue and high-mindedness in the business’s most visible office, he almost single-handedly made the N.F.L.’s game and the N.F.L. itself safe to believe in.

Rozelle has his own low-key but upbeat way of explaining how all this came about. “I think it’s the action,” he explains. “Americans love action, and football is well suited to television. It is also well suited to the fans in the stands. Balanced competition is a big factor, too. Traditionally, nearly 50 percent of our games are decided by seven points or less. On any given Sunday, any N.F.L. team really can beat any other. The fans in most of our cities can hope that they can actually win the Super Bowl. That’s not true in any other sport.

“It is very important that we keep the public emotionally involved and caring enough to watch on television and to buy tickets to the stadium. It’s important that we hype the Nielsen ratings. But, to a great extent, the product carries itself. We have a hold on the public that I don’t envision going significantly downhill.”

“It is very important that we keep the public emotionally involved and caring enough to watch on television and to buy tickets to the stadium. It’s important that we hype the Nielsen ratings. But, to a great extent, the product carries itself. We have a hold on the public that I don’t envision going significantly downhill.”

Commissioner of the National Football League is one of the most visible jobs in modem American life. By now, Rozelle’s person and role are virtually indistinguishable to the public eye. Ironically, there is little of the hard-nosed aggression Americans have come to expect from the N.F.L. in his actual presence. In football terms, there are no pulling guards turning Pete Rozelle’s personal comers; he blitzes rarely and never on first down.

He is now 57 years old, and stands 6 feet 2 inches, much taller than he seems on television. He is balding slowly, and his face carries a hint of the family dog in its jowls. His suits are custom-made but unpretentious. His office is large, but decorated in inconspicuous browns and greens. It features almost no football memorabilia. In person, he is still the man the Dallas Cowboys’ owner Clint Murchison, Jr. described as having ”milk toast all over his high hand.” He offends no one, if possible, and makes a point of getting along. He has been a public relations man since age 20 and is arguably the most successful figure in the history of that profession. He makes himself easy to underestimate and reinforces that underestimation with self-effacement. “A lot of it is no fun,” he says of his job. “I agonize over the decisions I have to make. I suppose my public relations background was helpful – the public relations business is just getting along with people. I’m not a confrontational-type person, but I learned right away that I wasn’t going to make every.”

Rozelle regularly describes himself as just an employee of the 28 N.F.L. franchises, but few employees have his kind of authority. He is empowered to settle all disputes between two or more of his employers, between any of his employers and their employees, and between his employers, their employees, and himself. He acts as the league’s sole public representative and, in the words of the N.F.L. constitution, can “interpret and from time to time establish policy and procedure.” He is also charged with “any enforcement thereof,” and, to do that, his office retains 28 investigators in 26 metropolitan areas.

Rozelle is also a one-man judiciary who rules on most charges that might be raised against the league and Its owners and players. The only official requirement for his job is that it be filled by “a person of unquestioned integrity” who will post a $50,000 surety bond. Other than contract expiration, the N.F.L. constitution specifies no provisions for removing the commissioner from office. Rozelle is the only person mentioned by name in the constitution’s text. His current contract pays him $.500,000 a year plus generous benefits and still has at least nine years to run. “Some people call them powers,” Rozelle says of his considerable prerogatives. “I prefer to call them responsibilities and obligations. The public may disagree with me, depending on what I am involved with, but they don’t know me. I’m sorry I can’t have more head-to-head exposure with more people. I’ve seen it written that I’m slick, but I don’t think I’m slick. I just believe in advance preparation and knowing what you’re dealing with. I’ve been accused of being hard, but I don’t think I’m that, either. I torture over discipline. I don’t thrive on publicity, but I know it’s part of my job.”

Most of the work Rozelle will do at next Sunday’s Super Bowl game in Tampa, Fla., will be in the public eye. He will watch the game with his wife, Carrie, and a group of close friends in the box normally occupied by the Tampa Bay owner Hugh Culverhouse. Afterward, he will present the Super Bowl trophy in the winner’s locker room. On camera, he will appear dignified, convincing, and easy.

Pete Rozelle’s job is not, however, nearly as easy as he himself seems to be. It has been four years since his last vacation, and fatigue shows in his eyes.

When Rozelle was first hired to be commissioner in January 1960, few expected him to be much of a success. Prior to that year’s league meetings at Miami’s Kenilworth Hotel, he wasn’t even considered a candidate to replace the late Bert Bell. Rozelle was then 33 years old and the general manager of the Los Angeles Rams. He had started his off-again-on-again career in the professional football business 14 years earlier as a training camp gofer, working for the man who did public relations for the Rams.

Rozelle’s name finally came up In Miami after 23 unsuccessful attempts by the team owners to reach agreement on any of the more obvious candidates. It had taken nine days for the group to think of him. ”I was known to most people in the league as a nice guy,” he remembers, “but I knew none of the big boys very well.” The “big boys” in those days of the N.F.L. were the New York Giants’ Wellington and Jack Mara, Paul Brown of the Cleveland Browns, Art Rooney of the Pittsburgh Steelers, Dan Reeves of the Rams and George Halas of the Chicago Bears. Wellington Mara and Brown put Rozelle’s name forward. “The reason I was selected was probably that I was the only one who hadn’t alienated most of the people in that meeting,” Rozelle explains. They said I’d grow into the job and that, in effect, is what I did.”

Before accepting the commissionership, Rozelle took a walk with his friend Bill MacPhail of CBS Sports. “Pete never makes snap decisions,” remembers MacPhail, “and he gave it careful thought. He didn’t just jump into it. He wasn’t overcome with its glamour and money. He worried over the size and difficulty of the job. It took him a while to say yes.”

When Rozelle’s name was announced to the press swarming in the Kenilworth’s lobby, it seemed to have come out of nowhere. He was quickly dubbed “the boy czar.” It was not long before a number of N.F.L. observers were giving odds that Rozelle would last no more than three or four years before the owners devoured him and found someone more seasoned. It was hard to imagine that a figure as amiable as Rozelle would be able to handle the notoriously carnivorous egos for whom he was to work.

The owners of the teams that constitute the National Football League are a group whose current incarnation is described by Gene Klein, owner of the San Diego Chargers, as “28 successful, hard driving individualists.” Hugh Culverhouse, owner of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, uses the description “28 kings.” Leonard Tose, owner of the Eagles, calls them “28 egomaniacs.” Art Modell, owner of the Cleveland Browns, suggests “28 idiots, myself included.” Their collective character has changed little over the years.

Even so, today’s “big boys” pay Rozelle unstinting tribute. Modell, a member of the league’s three-man television committee along with Rozelle and Klein, calls Rozelle “easily the best commissioner in the history of sports.” Tex Schramm, general manager of the Dallas Cowboys and a key member of the league’s Competition Committee, calls Rozelle “one of the great persuaders of all time.” Rooney, the acknowledged figurehead of the league’s old guard, says that “Pete had more to do with our growth than anybody. We are very, very fortunate to have had him.” Rooney’s son, Dan, president of the Steelers, adds that “Pete thought league from his first day on the job,”

The seminal act in Rozelle’s “thinking league” came In 1961, when he convinced the owners to sell all the league’s games as a single television package and to split the proceeds for that sale evenly among all franchises, regardless of their individual media markets. Until that time, each club had sold its own television rights for widely divergent sums. “The boy czar” persuaded his employers that the key to marketing the N.F.L.’s product was maintaining a consistently high level of competition among all the clubs, a goal that could best be reached by limiting the clubs’ competition off the field. If each franchise were left to shift for its financial self, Rozelle argued, the ensuing division into rich and poor would give a few teams enormous advantages. This would create a corresponding imbalance on the field, greatly lessening the attractiveness of the league as a whole. In the long run, that would cost everyone money.

Rozelle’s idea was to transform an organization built along feudal lines into what he now describes as “a single entity, like Sears or McDonald’s.” Its implementation has meant that although each team keeps separate books, at least 97 percent of the teams’ gross revenues are subject to sharing arrangements with the rest of the league. It has meant, too, that virtually all significant activity apart from on-field strategy is subject to the commissioner’s approval, or an affirmative vote of at least 75 percent of the 28 teams. Ed Garvey, the former executive director of the N.F.L. Players Association, calls the arrangement “socialism for management.”

Over the last 10 years, at least four different Federal District Court judges, responding to lawsuits from players and other parties, have called various aspects of the idea “in restraint of trade.” Three of the cases have been resolved by settlement or by changes in the way the league does business. The fourth and most troublesome case for Rozelle is on appeal.

“I was lucky,” is the way Rozelle begins his description of how his system succeeded. “The owners were very kind to me. You have to be patient with them and when they’re up-tight and angry about something, you’ve got to be cool, get as much information on the subject as you can and try to convince them with logic, using as a basic premise the fact that when we stay together on something, we’re normally successful and we grow. When we’re going to splinter off, we’re not as successful. It’s mainly just patience, calm preparation, with, I guess, a degree of political persuasion.”

“A degree of political persuasion” is perhaps the most extreme of his understatements. “Rozelle is as skillful a politician as I have met in my life,” says one longtime N.F.L. insider who has watched the commissioner operate with his employers. “His capacity to conjure up agreement is sometimes nothing short of miraculous. He’s a consummate politician, as good as I know, and I say that approvingly.”

Rozelle operates with a careful assessment of league dynamics and, as a consequence, strokes his employers whenever possible. Having seemingly little ego at stake himself, it is easy for him to be deferential and circumspect and he invariably is. The mechanism he uses to communicate is the single-spaced, uncarboned letter on his personal stationery. Rozelle types them himself on a manual machine in his office. Everything is written in the lower case, names included. The commissioner reportedly types hunt-and-peck style with two fingers, and he uses X’s to scratch out his mistakes. His associates do not know where this style originated, but within the N.F.L.’s warlord politics, the receipt of such a hand-typed letter is reportedly a sign of favor. The regular receipt of such letters is taken as a sign of power itself.

Another aspect of Rozelle’s style is his way of holding his ground patiently while grinding down the opposition with persistence and calm. The late George

Marshall, a contemporary of George Halas and at the time owner of the Washington Redskins, first experienced Rozelle’s technique when “the boy czar” visited him and asked a searching question about team business. “Young man,” Marshall berated him, “you were in diapers when I started this league.” Rozelle listened respectfully for a long time and heard a lot of history. “Mr. Marshall,” he finally answered when the owner had finished, “you still haven’t answered my question.” The meeting ended when “the boy czar” got the agreement he had come for.

Along with doggedness, Rozelle has an extremely facile intelligence and a reputation for being able to master any subject quickly. “Pete became his own TV man within a year of taking the job,” says his friend Bill MacPhail, now with Cable News Network, “and he’s been one of the best ever since.” “Pete Rozelle may be the quickest take I’ve ever seen,” says Joseph W. Cotchett, attorney for the Los Angeles Rams. “We’d run him through unfamiliar trial material for two hours and, by the time we were done, he’d already mastered it.”

To that quickness, Rozelle adds a penchant for what he calls “preparation.” Simply put, he never talks about anything without first being convinced he has the answers to whatever possible questions might come up. And he rarely raises an issue without getting all his ducks in a row first. If, going into a meeting, he does not have the support to win a motion, he does not make it. Modell, Klein, Schramm, and Culverhouse are all said to be key players in that process. Such “preparation” is central to Rozelle’s capacity to exercise power from a position of seeming passivity.

All this has enabled him to come out on top in a running series of struggles with several of his employers. His longest-running skirmish was with Carroll Rosenbloom, a textile manufacturer who entered the league in 1953 and owned the Baltimore Colts until 1972 and then the Los Angeles Rams until his death in 1979. Rosenbloom was mad at Rozelle off and on for more than a decade. In 1975, he went so far as to hire an investigator to find whatever private or public dirt he could to discredit the commissioner. The private eye’s search came up empty. At the league’s next executive session, Rosenbloom launched into what Art Modell described as a “slashing attack,” according to The New York Times. Finally, Rosenbloom stood up, pointed at Rozelle, and declared that he would never attend another N.F.L. meeting so long as “this man sits in the chair.” He stormed out.

Rozelle watched him go. “Anyone who would like to talk to me privately about the charges you just heard, feel free,” the commissioner told the other owners, “but for now, let’s continue the meeting.”

The two men eventually “got back together,” as Rozelle described it, and Rozelle stayed in the chair.

The commissioner’s private life has, in fact, little of the extravagance the public expects from entertainment moguls. “With Pete,” Tex Schramm points out, “what you see is what you get.” The closest thing Rozelle has to vices are a considerable cigarette habit and a taste for “a couple” of Rusty Nails (Drambuie and Scotch) on the rocks after dinner. “They help me relax,” he explains. Rozelle has attended an occasional horse race over the years, at first always refusing to place a bet. The first time he did, he had his friend Bill MacPhail go to the window for him.

Rozelle lives quietly on three acres in Harrison, in New York State’s Westchester County, and commutes to Manhattan in a chauffeur-driven Ford station wagon. The driver is paid by the league and the station wagon is provided gratis by Ford, a big N.F.L. television sponsor. During the season, he spends some weekends on the road showing the commissioner’s flag and some at home, watching the N.F.L. on television and calling around the country on the telephone.

The hub of Pete Rozelle’s life outside the league is Carrie, his wife of 10 years. It is the second marriage for both. She is slim, well-dressed and possessed of what one acquaintance calls “a genuine smile.” She has a reputation among her friends for being both “charming” and “sincere.” A Canadian educated in England, Mrs. Rozelle’s nickname is “the Queen Bee.”

When Rozelle travels, Carrie goes along. Their friends believe they have not spent a night apart since their marriage. “They weren’t wedded,” one friend jokes, “they were welded.” Rozelle’s daughter from his first marriage is now in her 20’s and on her own. Of Mrs. Rozelle’s four children from her first marriage, the three boys suffered from, and overcame, learning disabilities.

With Rozelle’s encouragement, she founded the Foundation for Children with Learning Disabilities. Most of the Rozelles’ outside night life takes place on the charity circuit. Along with Carrie’s foundation, the Rozelles’ principal commitment is to the United Way of America, the nation’s largest charity. One commercial broadcast minute in each game is reserved for the league’s use, and it was Rozelle’s idea to donate about half that time to the charity. The N.F.L. is, consequently, the United Way’s most visible salesman, and last April Mr. and Mrs. Pete Rozelle were awarded the United Way’s Alexis de Tocqueville Award for exemplifying the ideals of voluntarism.

The social life Rozelle enjoys most is small dinners with close friends. The sport in his private life is tennis. He and Carrie have a court in Harrison and play doubles with their friends whenever possible. Rozelle rates himself a B-minus player with a faulty ground stroke. His tennis-playing friends say Rozelle plays “competitively” and prefers to win. For other entertainment, the Rozelles occasionally visit the home of their Westchester neighbors, Bob and Joan Tisch, to watch advance screenings of the movies distributed by Loews. Bob Tisch is president of Loews Corp. Rozelle reads a lot on the job but not much outside it. “I don’t like deep books,” he says. The last book he read was “Hollywood Lives.”

In truth, the closest Rozelle has to a dark secret in his past is no longer a secret at all, for he readily admits that his real name is not “Pete” or “Peter.” It is Alvin. Each of his parents blamed the other for having chosen to call him that. Rozelle’s grandfather had migrated to California to farm 100 acres along the Los Angeles River in 1891. His father lost a Lynwood, California, grocery business in the Depression and eventually retired as an assistant purchasing agent for the nearby Alcoa aluminum plant. Rozelle’s uncle, a junior high school coach, rescued the boy from the burden of being named Alvin; following the uncle’s lead, everyone started calling Alvin “Pete.” He has been “just Pete” ever since.

Being “just Pete” was a natural part of growing up in a place like Lynwood. The ambiance of his southern California childhood is still stamped on Rozelle’s personality and his commissionership. He describes his childhood as “very happy. I think I came out with a lot of my father’s attributes. He had a lot of friends. He was a very good guy. I probably got his patience. He was a very calm person.”

Rozelle’s friends say his sense of humor is often obscured from public view by his role as the moral guardian of America’s game. “There is a lot of the little boy in Pete,” Bill MacPhail points out. “He’s a lot of fun and he’s also very funny.” Perhaps the most typical example of Rozelle’s wit occurred at the time he got the job as commissioner. While the owners discussed his candidacy, Rozelle walked unnoticed through the press in the Kenilworth lobby and hid out in the hotel men’s room. Every time someone else entered Rozelle put out his cigarette and, trying to seem inconspicuous, washed his hands. After what seemed at least a dozen such washings, he was finally summoned to the owners and offered the job.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “I can honestly say that I come to you with clean hands.”

Every year for 24 years, Rozelle has made the N.F.L. owners richer than they were the year before. His capacity to deliver has been, in large part, a function of television. The N.F.L. ‘s success in that medium is itself a case study in both Rozelle’s luck and his hard work.

Rozelle was lucky to be named commissioner at the very time television was emerging in its modern form so that much of TV’s football achievements became indistinguishable from his own. At the same time, the marriage between television and his employers’ game was hardly a given when he began. In the early days, when stations often made more money broadcasting Sunday movies than sports, Rozelle worked the CBS affiliate meetings, rubbing elbows with the locals and building a base for promoting the N.F.L. product.

Rozelle was also lucky to start his television offensive at the same time the challenge to the N.F.L. and CBS from the competitive American Football League and NBC had already begun to generate public fascination. When the two leagues merged in 1966, that fascination attached itself to the Super Bowl, the game played between the leagues’ modern incarnations: the American and National Conferences. Its audience soon became geometrically larger than that for any of the football championships that had preceded it. Luck or not, when a limited antitrust exemption was needed from Congress in 1966 to allow the leagues to merge and actually play a Super Bowl game, it was Rozelle who went to Washington and got it.

Especially helpful in that merger process was the late Representative Hale Boggs of Louisiana. Rozelle reportedly enlisted Boggs’s support by promising the next N. F .L. expansion franchise to New Orleans. According to one of Boggs’s former staff members, the following conversation took place between his boss and Rozelle immediately preceding the House vote on the antitrust exemption:

“Well, Pete, it looks great.”

“Great, Hale, that’s great.”

“Just for the record, I assume we can say the franchise for New Orleans is firm?”

“Well it looks good, of course, Hale, but you know I can’t make any promises.”

“Well, Pete, why don’t you just go back and check with the owners. I’ll hold things up here until you get back.”

A pause.

“That’s all right, Hale. You can count on their approval.”

An hour later, the House passed the N.F.L./ A.F.L. merger exemption. Later that year, the New Orleans Saints, owned by the Texas oil heir John Mecom Jr., were born. Mecom paid the other owners a reported $8.5 million for the franchise rights. Once Rozelle’s hard-won exemption gave rise to the Super Bowl, the N.F.L.’s golden era of video began. Today, the attractiveness of the N.F.L. product has become the stuff of ad agency legend. National advertisers were willing to pay NBC as much as $900,000 a minute for spots in last year’s Super Bowl telecast. The heart of that advertising attraction is that N.F.L. programming draws nearly six times as many men between the ages of 19 and 55 as even the highest rated television series. That male audience is considered both the most difficult market to reach and the most potentially lucrative. That is why the N.F.L. has a five-year, nearly $2 billion contract with the three networks. When that package was consummated, Ed Garvey, then the Players Association executive director, said: “A team could conceivably make $4 million or $5 million profit without selling one ticket.” The N.F.L. denies the claim.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of Rozelle’s career is that, despite all the arguments and skirmishes, he has only one genuine enemy. That enemy is Al Davis, managing general partner of the once Oakland, now Los Angeles Raiders. In 1980, Davis sued the N.F.L. for violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act when it refused him permission to move his team to southern California. In 1982, a Los Angeles Federal District Court jury sustained Davis’s charges and, in 1983, awarded him $35 million in damages. In the trial, Davis was the principal witness for the plaintiffs and Rozelle the principal witness for the defense. Except on official occasions, they have hardly spoken to each other since the suit was filed. “There is a real hatred there,” says an N.F.L. insider who has observed the two men go at each other in executive session. “It’s absolutely awful. Davis almost reaches apoplexy about Rozelle. He goes berserk. Rozelle contains himself but the venom is just as stringent.”

From the beginning, Davis framed his case as a matter of Rozelle versus himself, one on one. “Rozelle has become the most powerful man in sports,” Davis told The New York Times. “The league probably has the most massive media control of any organization in America other than the President. I admit he’s been brilliant at public relations. But he has used what he could to gain personal power, to secure his job. What the N.F.L. has become is a political theater. If you’re not in the inner circle, you’re exiled.”

“I guess,” Rozelle responds, “it serves Al’s purpose to have all this seen as a personal thing between him and me rather than him and his 27 fellow owners. I hope you understand that I don’t feel the same way.”

Even so, the Davis affair seems to have gotten under Rozelle’s skin to a degree no other skirmish ever has. “How could it not?” asks Art Model!. “Davis made it all personal and Pete’s not that kind.”

Rozelle admits, “It was personally troubling”. He says the most painful part was that his father, who died last summer at age 83, had to spend his final years reading “that stuff” Al Davis said in the Los Angeles papers. “I suppose Pete may have lost his cool a little with Davis,” one of the commissioner’s friends allows, “but it hurt Pete deeply that his integrity was challenged. It was the first time that ever happened to him. I didn’t see much of him while the trial was going on – he was always out on the West Coast- but when I did, sometimes it scared me how down he looked. That seems to have passed now. We talked about it, and I think he has it all in perspective. He understands you can’t let mishaps dominate your life. Pete’s cheery and confident again.”

He had better be. Rozelle’s job only gets harder from hereon in.

“Under the precedent set by the Davis case,” Rozelle says, “every one of our league meetings could potentially be challenged as a conspiracy. It’s a real can of worms. What the Davis case created was, in effect, franchise free agency. As of now, the league as a whole has no firm legal footing. Antitrust exemption is clearly the priority of this decade.”

Despite his deserved reputation as an excellent legislative witness, and even with the services of several prestigious Washington lobbying firms, Rozelle’s attempts over the last three years to secure such a blanket exemption have come up empty. “It as poor timing,” he explains. “We’ll probably wait until the Davis case is resolved on appeal to try again. Frankly, I’m worried about just what may happen next. When one person can get away with violating the prime rule of the league, it sets the stage for others to follow.”

In the meantime, the organization of the football business is up for grabs to an extent unseen since Pete Rozelle was plucked out of nowhere at the Kenilworth Hotel.

At the 1984 league meetings set for Hawaii in March, the legal future of “thinking league” will no doubt be one of two primary topics for discussion. The other will be television.

Even if next Sunday’s Super Bowl audience sets records, this football video year has been a semidisaster. According to ratings through November, the audience for CBS’s N.F.L. package had shrunk by 400,000 households, for NBC’s by almost a million, and for ABC’s primetime Monday nights by more than 3 million. It could be no more than a momentary dip or it could mark the end of almost a quarter century of audience growth. If it is the latter, the television contract negotiated by Rozelle in 1982 appears to have been seriously overbid by the networks. Last November, advertisers were seeking compensation for lost audience from the networks, and the networks were, in turn, seeking the same thing from Rozelle. This March’s meetings reportedly will consider network requests to adjust the terms of their television contracts and increase the amount of advertising space during the two-minute warning and at halftime.

In N.F.L. circles, there are four principle explanations for why the audience left. The first is what Rozelle describes as “balmy early-season weather that kept people outside” rather than in front of their sets. The second is that off-season drug scandals among the players reinforced some of the negative image left over from the 1982 strike. Rozelle hopes he has curbed that damage with his new, tougher policy of suspensions for admitted drug use. The third reason is the United States Football League, the N.F.L.’s new springtime rival. While it is not a head-to-head ratings competitor, year-round exposure to football provided by the U.S.F.L. seems to have at least taken the edge off audience anticipation in the early stages of the N.F.L. season. “I’ll give them an incomplete,” Rozelle says of the rival league. “Their payrolls are going to go up, as ours are, but for the time being we’re in better shape to pay them. I would think this year would be a key year for them.”

The fourth reason advanced for lost N.F.L. audience is the one in widest public circulation. This season has been marked by an unusually high number of either lopsided or uninteresting match-ups, especially on Monday nights. It has become a common occurrence for the commentators – Howard, Frank, O.J. and Dandy Don – to be reduced to situation comedy before halftime. Sports Illustrated went so far as to describe the N.F.L. as “Borrr-ing” on one of its December covers, and a number of columnists have laid that lack of excitement at Rozelle’s doorstep. The commissioner’s obsession with “league think” and “on-the-field parity” has, in his current critics’ eyes at least, made the N.F.L. into 28 different brands of indistinguishable mediocrity. Rozelle finds such conclusions at best hasty. “Each year is different,” he points out. “Anything can happen in football. Unfortunately, that includes blowouts. Over all, that unpredictability is one of the league’s strengths. It is, after all, a game.”

It is also, lest we forget, a business. As such, Rozelle claims, “We’re still in good shape. We still have a firm hold on the public, and the owners are still good at reaching agreement. The question now is whether we can live with success.” Having convinced his 28 employers to think league when money and markets were growing geometrically, the commissioner must now try to keep them agreeing with each other when the boom is, at least for the moment, flattening out.

“Like I said,” Rozelle repeats, “the question now is whether we can live with success.”

Pete Rozelle’s answer to that question will test his reputation and character as they have never been tested. It is what the remaining nine years of his contract will be all about.

Leave a Reply