Rolling Stone – April 12, 1973

LOS ANGELES- There’s a vampire downtown. At least that’s what the people on Fifth Street say. As a matter of fact, Fifth Street has seen six of them. The monsters bunch together on either side of the street between the tracks and the Greyhound bus station. They’re not hard to spot. Most of them don’t have windows, but you can tell them by their signs. The signs are small, up-front, and say BLOOD.

Needless to say, the people who’ve seen them are very down on vampires. They may have reasons for it, and some of them are doing something about it, but even they have to admit it’s a good business. All it takes is $300, a doctor within a 15-minute drive who’ll swear that the help you hire knows a vein from an artery and you’ve got a state license. Then you rent a storefront and buy the equipment. You need tables, stands, plastic bags, tubes and needles to get the blood out at the crook of somebody’s arm. Then you have to get a centrifuge and some technicians to make the blood into plasma. When you’ve got the blood, a pint at a time, you need enough ready cash to pay $5 to the guy who used to have it in his veins. All there is left to get after that is a connection. It’s not hard. A lot of hospitals use a lot of blood these days and there’s never quite enough to go around. When you get it ironed out, just send the pints on up each day in a cab. The hospitals will give you anywhere from $40 to $65 for each pint , depending on the market and the type. It’s a good business. It’s grown 10% each year of the last two and promises to do the same in 1973.

Of course, the folks with their cash tied up in the operation don’t call themselves “vampires.” They’re a business, a legitimate business licensed by the State of California. They call themselves things like Doctors’ Blood Bank, California Transfusion Service, United Biologics and Abbot Laboratories. Inc.

The people who do call them vampires are somebody else with a little less standing in greater Los Angeles, but they may still be right. After all, they ought to know. They live right next door.

These name-calling neighbors have a long record of being called a few names themselves. Over the years it’s been “tramp,” “wino,” “deadbeat,” “derelict,” and “vagrant” until it comes out of their ears and the pores of their skin.

They don’t call themselves any of those things. lf you ask them, they’ll tell you they live on The Row, on Skid Row, down on Fifth Street. And they mean it. It’s their word. They are honest about themselves. It’s a skid they know they’re in: whipping around the surface of a spin, heading for the guard rail, the edge, and off into space. On this street corner there’s a divorce in Cincinnati and on the other there’s a layoff in Gardena. They aren’t lucky people. They are ex-carpenters, ex-drill press operators, ex-cowboys and Indians. If you ask them what they’re doing now, they’ll tell you they’re between things. At the moment, they seem to have their hands full just being poor, hungry, cold and miserable.

“It’s not the misery we’re yelling about,” the “derelict” Bill Skahill says. “It’s the people that come down here and live off it that’s got us mad.”

• • •

The daily pay outfits are known on the Row as “the slave marts.” The lines at their doors start forming under the street lights at five in the morning. Right by the sign that says READY MEN. It’s early, but not too cold. That’s why the men are in L.A. They’re called “snowbirds.” They fly in for the winter and leave when the crops come in up north. The lines have been harder this year because of the rain. It’s made work slow too.

Hiring starts at six. Every outfit has its regulars and they go first. The rest of the jobs are ladled out to whoever is first in line and sober. Work is anything from loading boxcars to putting labels on jars of mayonnaise. The company pays the slave mart and the slave mart pays the minimum wage. No one is sure what the slave mart gets first, but the most common guess on the Row is three and a half.

If you miss at the slave mart, you can run down the block to the bill passers. They’re door to door advertising companies who leaflet the suburbs. Six dollars for eight hours and a ride out and maybe back. Some have a habit of leaving men in Pasadena and not picking them up. When you hitchhike in, they give you your check. Sometimes. A few are known to say you didn’t distribute enough handbills and slam the door.

Working for the bill passers is risky business and a lot of men avoid it. A good number don’t have any choice. They are too old to walk around Pasadena and some are crippled. The only place for the back part of the line, the old men, the drunks, and the disabled is the missions. And that’s like having no place at all.

The missions are perched on every dungheap and stuffed into every corner for 20 square blocks. They solicit contributions with a city permit and bring the burning word of Jesus to the downtrodden, the sinners and the drunkards. To every poor son ofa bitch who’ll come in from the cold. The biggest one has a neon sign 40 feet across along its side. THE WAGES OF SIN IS DEATH it says, BUT THE GIFT OF GOD IS ETERNAL LIFE.

Some of the missions give a bed. It’s usually one night in, then ten nights out before they’ll give you another. If you take it, you’re locked in until time for chores at 8:30. It’s no way to find work. All the work splits by eight. The best deal is one of the pews in the chapel. That way you can roll out at five and make the slave mart in time for a chance.

All of the missions give a meal. A Bean Meal spelled with a capital B. Some serve their beans at 11, some at one in the afternoon and some top the day off with beans at 8:30. A couple give salads. One, the Union Rescue, has a health and dental clinic that’s free on Saturday morning. It can handle 25 men. The missions are all sizes and tastes. The biggest has 500 beds, the smallest has four and is open on Tuesdays and Thursdays. They come big and tall, fat and small but the talk of the Row is Gravy Joe’s. Everybody says it’s because of the gravy.

• • •

If you get tired of Gravy Joe’s and you can’t get on at Ready Men, there’s only one thing left to do. Just find your nearest neighborhood vampire. If you pass the iron test, you’re all right. After a while you get used to it and start shaping the whole mess into a life.

Richard Morgan has. He’s been doing it ever since he left the Army I I years ago. From New York to L.A. up to Portland for a while then back down south again. Now he’s on the staff of the Union Rescue Mission. He rolls the men out in the morning, sweeps up and shows the new ones their bunks at night. He gets a room, board, and four dollars a week. It’s a good job. He’s been after it for ten years and worked his way up. To top it off with an extra ten bucks, he goes down to the plasma daily twice a week and works as a cow.

It’s called “being on the program.” The nurse takes a drop of your blood and drips it into a vial of light green liquid. If it sinks, you’re in. If it doesn’t, you can go out, get a four-ounce glass of water, put five drops of iodine in it, drink it and pass in an hour and a half. Everybody knows how to do it. It’s part of the Fifth Street grammar.

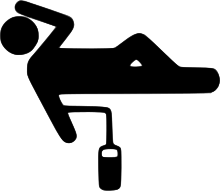

When you’re past the nurse and the forms, you lay on the table and get plugged in. The needle leads to a tube that leads to a plastic sack. When the first sack fills, a second is plugged in. The first pint of whole blood is taken back to the lab. This is all happening at 50 beds, one right after another and the lab is covered with plastic sacks. One by one they are put on a centrifuge until the red blood cells sink and the plasma floats over them. Then the plasma is sucked out and the red blood cells taken back to the arm they came from. If the nurse switches sacks and gives you someone else’s, it means a county grave or three months in the hospital at least. The first form you sign when you sell your blood is a waiver that frees the blood bank of any liability in case they fuck up. The whole process takes two hours or an hour and 40 minutes if you have good veins. Two pints of blood are extracted to get a pint of plasma. Twice a week is the legal maximum but that’s easy to beat if you need to. The blood banks only check between each other by putting a mark on the thumb with ultraviolet ink. It comes off with a short rubbing of battery acid or a mixture of lemon juice and bleach.

When you’re all done, just go down the hall to the cashier’s window. The nurse gives you a nickel to use in the coffee machine on the way. The cashier pays the five bucks. She’ll hand over eight if you let the nurse inject tetanus serum with the red blood cells when they drip them back in. The doctors are trying to find out what it does. It seems that nobody knows yet and they want someone on Fifth Street to be the first one to find out.

Rich Morgan won’t. “I’ve got to take care of myself,” Rich says. “I mean who else is gonna if I don’t? These goddamn blood banks won’t that’s for sure.”

• • •

“Nonsense,” is the way one of the doctors on Fifth Street responded. He didn’t want his name used but he was short, sixty and Jewish. “We treat them beautifully,” he says. “I check them all for blood pressure. I have eight assistants and 15 in the lab downtown. That’s not the problem.”

“The problem you see is the men down here. Some are nice but the rest. They are driftwood. Just driftwood. Give them more money and they’ll drink more. They have less intelligence than an insect or a spider. Because a spider has a plan and builds a home. It plans its life. These people don’t. The have another 50 years to live. Have they got a plan for their lives? No. They’re bums. They have no place to sleep. The solution to help these people is not to make trouble. The solution is to organize a kibbutz for the people.”

When we talked, the doctor shouted at me over the constant scramble on the street. “The problem that you have to solve is what you call the drifters; this driftwood here.” The doctor was standing in a doorway across the street from his bank and gestured at the passing wreckage. “You gotta organize it into something structural. Something that has positive value. Look at this one who stands here. Or this one there. Does he have a plan? I ask them. They talk back . ‘Did you have a plan?’ they say. I say yes. Since I was 14 years old. I planned my, life and I got it.”

The doctor has five college degrees and a home on the other side of town. While we were talking, two men on a Coke truck were delivering next door. They overheard.

After the Doctor left the one on the top shouted down.

“Is he a for-real doctor?” he asked. “I see his white coat. but I mean is he for real?”

“He seems to be,” I said.

“Good Jesus Christ.” the man mumbled. “Ain’t that a bitch.”‘

The Doctor is for real, no doubt, but there are still a lot of men on the Row who tell a different story. They could tell enough to keep you a month. Fortunately, there’s a way to make sense out of all the claims. The commercial blood banks all over the United States have a track record and it seems to point in one direction. There are two parts to it.

The first one is a long way from Fifth Street. It’s in suburban hospitals all over the country. It’s called serum hepatitis. It inflames the liver, causes extreme pain, itching, weakness, diarrhea, nausea, fever and yellowing of the skin. You get it from transfusing dirty blood.

When the suburban doctors try to figure it out, they point at the commercial blood banks. Outfits like California Transfusion Service and Abbott Laboratories, Inc. are responsible for 47% of all the blood and plasma transfused in the country. The only regulations they operate under are those of the Federal Division of Biologic Standards. That code demands a certain extraction technique and freedom of the donor from infectious skin disease. If all you are is pregnant, syphlitic, feverish, infected with mononucleosis, tuburcular, suffering from upper respiratory infection, cancer, kidney or liver disease, then you can give. The bureau has checked 500 of the 7000 commercial blood banks this year. By June it will have checked a thousand. Violations are a misdemeanor under the Public Health Services Act. Since 1902, the government has taken action against a total of four blood banks. In Los Angeles, up until three years ago, the commercial banks pooled their plasma. All the pints were mixed together. Until the practice was stopped, one out of every ten L.A. transfusions led to serum hepatitis.

A low estimate of the impact of the vampires is given by Dr. J . Garrot Allen of Stanford University, who has studied blood since 1945. He estimates 3500 deaths and 50,000 illnesses a year. The Center for Disease Control in Atlanta guesses higher. They put it at 35,000 deaths and 500,000 illnesses.

The second part of it is just as bad . It’s all over the street corners and sleeping in the empty boxcars at night. The men of Skid Row have wells in their arms. They live on Gravy Joe’s chicken delight and get the protein sucked out of their veins twice a week . It has withered them, made them dizzy, given them heart attacks and used them up. Every three hours, there’s an ambulance on the street. Now and then, a “vagrant” dies on the blood bank table. Men who give blood should eat steak and orange juice. As it is, the last piece of raw meat to make it past the Greyhound station was a policeman’s horse shot in an armed robbery.

Ray met one of the victims. He looked old and had pits in the lining of his elbows. He’d given plasma twice a week for three and a half years running. He was broke and none of the banks will take him anymore.

“They say I’m a health risk,” he said.

“What do you do for money now?” Ray asked.

“I sleep out in the weeds. That’s all,” the old man said.

Ray felt like he was watching the leftovers from a sausage factory. They had just used him up and thrown him away. It made Ray mad. That’s an important thing to know. You haven’t met Ray yet, but you can’t really understand what’s happening to the vampires now unless you understand Ray and Jeff and the thing the men have come to call the hippie kitchen.

It doesn’t call itself the hippie kitchen. But nobody down here seems to call anybody else by their right name. The kitchen calls itself the Ammon Hennacy House of Hospitality. It’s been feeding on the Row for three years and has been on the corner of Sixth and Gladys since 1972. It’s a kitchen. It feeds once a day, every day, from one o’clock until nobody comes, anywhere from 200 to 400 men a day. The hippie kitchen is the only one on the Row to give salad and fruit every day. It’s the first feeding outfit to break away from beans to spanish rice with little chunks of hamburger. It’s also the only place to eat without having to sit through a service. They just feed and don’t fuck with you when you’re trying to eat.

Jeff Dietrich has been there since the start. He’s short with a blond moustache and ponytail. He belongs to the Catholic Workers. His voice always has a smile in back of it and he means what he says.

“The missions have told these men that it’s a sin to be poor. We think that the teachings of Christ have nothing to do with that. It’s not a sin to be poor. It’s not a sin to be a drunkard. It is a sin to be a member of that kind of corporate, capitalist rip-off that put these men here. It’s an unchristian society that made the Row. It’s not the men living here who are sinners, it’s the men who own this place who sin.”

About a year ago, Ray Corrieo heard about the kitchen and came in. It didn’t seem like much then, but it’s meant a lot on the Row since. In 1966, Ray Corrieo was an ex-football player on the crew of the USS Kitty Hawk in San Diego harbor. He’d been on one bombing tour already and he was sick of it. His officer came by and Ray stopped him. ‘Tm sick of killing people,” Ray said. “I want out of the Navy.” His officer laughed . The next day Ray announced he wasn’t working anymore. He wasn’t going to eat either. Not until he got a discharge . After 20 days not eating in the brig, he was marched down the gangplank between a double row of Marines. The Marines spat on him every step of the way. After 52 days, Ray was down from l 95 pounds to l 25. He was in the hospital and the doctors said two more days would kill him. At that point the Navy gave in and he got his discharge. Three of the guys who spat on him came over to the hospital and apologized.

I probably don’t need to tell you that Ray Corrieo is a brave son of a bitch with a good record of fighting when he thinks he’s right. He hung around the Row and noticed the blood banks. That spurred his curiosity and he read every article printed about blood in the last five years. When he was done, he went in the kitchen and found Jeff.

“These guys are getting screwed,” Ray said. “We got to call a meeting and figure out what to do about it.”

They posted notices and had the meeting on the next Sunday afternoon. Jeff hoped for 12 guys to show. Ray was ready to settle for four. When the time came, the room had 70 people in it. They all knew they had been screwed. No doubt about it. That’s all they talked about for the next two hours. Bill Skahill was there and so was Rich Morgan and Just Plain Bill. At the end, they decided to send a committee around to the banks with a list of grievances.

As everyone was leaving, a guy came up to Jeff. He handed him a folded paper and said it was a statement about the blood banks.

“What’s your name?” Jeft asked.

“It’s on the paper.”

“Can we contact you?” Jeff asked again.

“I’ll be back,” the guy said.

The paper he left was short and simple. “I was laying on the table ,” it read, “and they’d just taken out the first pint of the two pints of blood for my plasma donation. I raised my head up on my fist and looked across the room at the guy on the table next to me. I saw the nurse unclamp the tube running out of his arm and. kick a trash bucket underneath it. She was letting his blood run out into the trash bucket and starting to walk away. When she saw me looking at him, she reclamped the tube but I know she would have let him die if I hadn’t seen her.” The statement was signed “Denny.”

Jeff looked for Denny after that but he wasn’t to be found. Someone in the lunch line said he went back to Wyoming.

• • •

The grievance committee got laughter at one bank and an “I’ll refer it to our legal department” at another. That led to a second meeting and the meeting led in turn to the union and the strike.

They call themselves the Blood Donors Union and anybody who has given blood can join. It’s simple: no dues and seven demands.

I. Respectful care and treatment.

2. The right to be advised. No experimentation on their blood without permission.

3. The right to informed consent. All processes must be explained by a doctor before they are done.

4. $15 a pint for whole blood, $9 a pint for plasma.

5. Abolition of the waivers of responsibility men have been forced to sign.

6. Their bodies are being drained of proteins by donation. The blood banks have an obligation lo replace it. Fruit juices and vitamin supplements for each man who donates. In addition. the blood banks should put a quarter into a union fund for each pint extracted. The fund will be used to build and staff a free medical and dental clinic.

7. For the protection of the general public, they recommend the introduction of central records-keeping for all the banks so the men suffering from hepatitis may be located and treated.

With that they threw up a picket line. They chose the Doctors’ Blood Bank. It’s small and specializes in whole blood. That makes it especially vulnerable. Whole blood only keeps 21 days before it has to be thrown out. If the union cuts into their action, the Doctors’ Bank can’t run on its reserves. The men wanted to leave the option for those needing money, so the union decided to take the banks one at a time. They hoped to break the Doctors’ and then move on to the others. The last thing they did was set the rules: nonviolence in response to abuse and no drunks on the line.

Then it was Tuesday morning, February 27th and every head on the Row snapped back. Pickets on Fifth Street? Nobody’d ever heard of it before.

Just being there was as big a victory as had been won on the Row since the Japanese surrender. The men in front of the liquor stores and magazine shops

cheered. Doctors’ went from a daily average of 120 pints to 24. The bank hired an off-duty cop to watch the lobby but even he dug it. He bought donuts and a guy just in from St. Louis brought coffee.

On the third day, Hot Cross Bun approached Ray. He’s called that because it describes his face. He had the misfortune of hitting Anzio, Palermo and Cassino right in a row with the 45th Division. The doctors took a woman’s rib and made him a nose with it.

“I’m due,” he said, meaning his officially prescribed waiting period was up. “I’m as goddamn due as you can get and have been for two weeks. But I’m not goin’ in. No way am I goin’ in.” He laughed and went up the street.

People’s spirits stayed high and they settled into their circle on the sidewalk eight hours a day, every day the bank was open. The only thing they hadn’t counted on was Miss Louise. She turned out to be a spoiler.

Miss Louise is as close to being Queen of the Row as anybody will get. She’s a black woman in her 40s and has been down there for the last 15 years. She runs the front counter at the Doctors’ Bank. She knows everybody and everybody knows her. She works for the vampire but she isn’t a hard or cruel woman. She’ll buy men drinks out of her own pocket when they can’t pass the iron test. Miss Louise tries to help them and has done just as many favors as pints of blood. She even brought plastic covers out for the pickets when it rained. Nobody in the union meant for her to, but she took the picket line personally.

Miss Louise doesn’t own the blood bank. It’s owned by six corporate directors. The only one of them anybody on the row has seen is a white guy who drives a Porsche. Still Miss Louise thinks of the bank as her own.

“How much of that quarter a pint are you gonna skim,” is what she started with. That didn’t work very well. Not many on the Row would buy it.

In the last few days, she’s switched to “you’re just picketing me because I’m black.” She stands in front of the door and says it to the brothers thinking about coming in. “Don’t let a little race prejudice stop you, honey,” she says, “come on in and let Miss Louise help you out.” It has hurt the strike. Not in numbers. Most everybody black, white, brown and red is going some place else if they have to go. It’s the division by color that has gotten a little nasty.

Twice black men have threatened to stick some of the folks on the line. Miss Louise didn’t send them. They came because of their feelings for her, but she knew nothing about it. The second time it happened to Curly. He was on the line and a brother with a floppy hat approached.

“You’re getting awful heavy on the sister’s action,” he said.

“It ain’t on the sister,” Curly said. “It’s against the bank.”

“If you don’t quit,” the man said, “it means trouble.”

Curly lobbied for a meeting and got it. The meet was supposed to happen on Saturday but the black guys never showed.

Out of frustration, Ray called Miss Louise.

“Well,” she said on the phone, “just what is it you guys want?”

When you talk on the phone, one thing leads to another and this phone call led to another meeting between the union and Miss Louise next Monday. She’s not management but she’s an important woman to everybody concerned. If everything goes well , the union plans to move across the street to California Transfusion Service as a tribute to Miss Louise’s willingness to talk.

It’s a step ahead for sure.

• • •

In the meantime, the pickets stay right where they have been for the last two weeks. Rain or shine, every day from six in the morning until the banks close at two.

Miss Louise remains in place on her throne in Fifth Street, sending a cab full of the day’s blood up to Huntington Memorial Hospital in Pasadena. If you’re a regular there, I’d try to stay away for a while. At least until the union wins its cross-checking system. Doing otherwise could prove to be a disaster.

Old Henry’s still down on the Row too. He comes every other day to lunch at the Hospitality House. Over the last 15 years he’s given 597 pints of blood and plasma. He thinks the strike is a great thing, but he’s afraid to join the picket. Some men who’ve walked with signs have been turned away at the other banks and he doesn’t want to risk it. He only has three more pints to make 600. When he does. his regular lab has promised him a $30 bonus. Down on Fifth Street that’s big money.

Leave a Reply