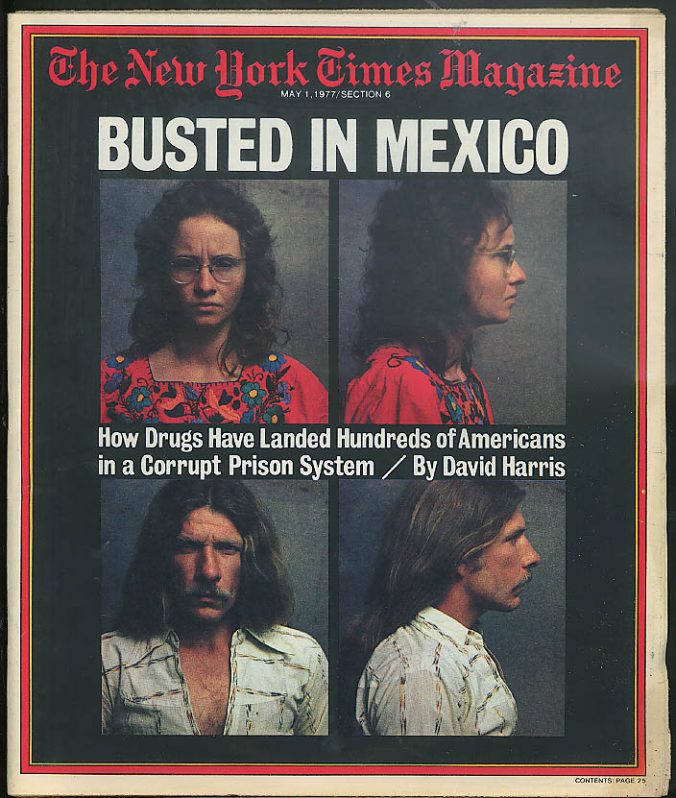

New York Times Magazine – May 1, 1977

Paul DiCaro and Deborah Friedman left Guadalajara on Thursday morning, Jan. 22, 1976. Three weeks of camping on the Pacific beach at Puerto Vallarta and visiting Paul’s American friends at Guadalajara University in west-central Mexico had reduced the couple’s finances to their last $40. Paul and Debbie were anxious to return to their Sonoma County, California home. DiCaro, 29, installs winery irrigation systems, and Friedman, 26, helps run their 55-acre co-op farm. Paul and Debbie have been living together for three years. The two Americans spent most of Wednesday night packing their 1963 Volkswagen. Debbie carefully hid the remains of an ounce of marijuana she had bought to smoke on the beach inside two cards sealed in envelopes and addressed to their house in Healdsburg, Calif., U.S.A. Debbie threw them in among 15 other letters in her bag, and she expected to mail the whole batch somewhere along the way. By 7:30 Thursday morning, Paul DiCaro md Debbie Friedman were on Highway 15 headed north across the state of Jalisco, 1,000 miles south of the American border.

The first few hours had all the earmarks of another mellow Guadalajara day. It was 80 degrees when they crossed the mountains and dropped down the long run through the cactus to Tepic. The sky was solid blue. Debbie was driving while Paul stretched out In the back seat and relaxed, or got loose, as he put It. Getting loose was some thing he rarely did In Mexico. This was his third visit in four years, and every time he went south, he tied his over-theshoulder hair up on top of his head and hid It under a wide-brimmed hat. The Mexican authorities dislike longhairs, and Paul DlCato wasn’t looking for trouble. But that day he didn’t expect to get out of the car for another 12 hours. He took off his T-shirt, combed his hair out and fell asleep In the back seat.

When he woke up an hour later, the day bad changed drastically. Debbie was calling him from the front seat:

“What’s this? What’s happening?”

Paul shook himself to attention. They were north of the town of Magdalena and had been surprised by a roadblock. A stop sign was planted in the middle of the two-lane road, and uniforms were milling around the cars parked on both sides of the blacktop.

“Aduana,” Paul answered.

Aduanas are a series of checkpoints set up along the Mexican highway system. The police camp there in sporadic 24-hour shifts and check all vehicles for guns or dope. Debbie stopped their VW next to the brown khaki Federal straddling the dotted line with an M-2 carbine strung over one shoulder. He bent down and put his face in the window.

“Por favor, your papers. Senorita. “

Debbie didn’t have them and had to ask Paul. The Federal looked at Paul’s hair and stared while Paul handed forward their passports, visas and car-insurance papers. The Federal thanked Debbie and looked at Paul again before going over to the group in uniforms on the road’s shoulder. When he finally returned, the policeman spoke rapidly in Spanish with an occasional English word thrown in. The couple’s papers were in order, but there was still some problem. The Federal wanted them to pull over to the side. He said he would have to detain them “for a moment.” It was9A.M.

That “moment” is the subject of this account. By 11:30 A.M., Dicaro and Friedman would be found to be in possession of an envelope containing marijuana-13½ grams, to be exact. Had they been stopped with the same quantity of contraband in California, they would have been issued a citation and fined $25. By 5 P.M., they would be charged with buying, possessing. trafficking, transporting and intending to export dangerous drugs, and they each would face a possible 57 years in prison. They would join some 600 other Americans In the Mexican prison system. the largest single group of this country’s citizens imprisoned in any foreign nation. Most of the arrests have been on drug charges. However. a good number have been for minor violations, and it is the treatment of those arrested or imprisoned that is the focus of attention and concern. This account was drawn from interviews with Paul DiCaro and Deborah Friedman and with dozens of others, as well as from documents and records in the Mexican court system and offices of both American and Mexican Immigration and diplomatic authorities.

Paul’s and Debbie’s nightmare began with a single marijuana seed that Paul says did not belong to them. Debbie had spent an hour the night before on her knees looking for seeds in the car’s upholstery. He says the seed belonged to the Mexican Federal Judicial Police.

That Thursday the Magdalena aduana was being manned by eight Federates armed with automatic weapons and two plainclothes Federal agents. Three Federales began combing through the car’s carpet, and two others stood beside Paul and Debbie; 50 feet from the car. Finally, Paul said, a young agent, wearing a bright polyester shirt, sunglasses and pointed boots, looked at Paul for a moment, walked to the car, bent over the doorwar for 10 seconds and stood up with his hand over his head. “Mira,” he shouted, “look at this.” He was holding one marijuana seed.

The “discovery” gave the police license to search everything. Paul was handcuffed with his hands behind his back and told to get down on his knees. Paul DiCaro got up off his knees twice in the next two and a half hours. The first time was when the agent came over to ask, in Spanish:

“Do you have any contraband in your car you want to tell me about?’

“No,” Paul said, struggling to his feet. Paul DiCaro wanted out of the vise he felt tightening around him. He continued talking in stumbling Spanish. “No ingés, amigo,” the agent said. “It , makes no difference,” Paul said. ” You can have it all. Sabe? The whole thing. The car. The sleeping bags. Everything.” Paul motioned with his head at the VW surrounded with brown uniforms. “It’s all yours. Just take us to the bus station and let us buy a ticket north.”

The agent laughed and pulled a fat wad of bills out of his pants pocket. “Muchos pesos,” he grinned before walking off. Paul took the response as a simple statement that the price was a lot more than an old VW and two sleepIng bags. A Federal motioned Paul back to his knees with the barrel of his carbine. Dicaro got on his feet a second time when the agent discovered the hidden weed. The agent was going through the mail in Debbie’s bag again and noticed that two of the unopened letters were addressed to herself in her own handwriting-apparently an obvious giveaway. He shouted and ripped them open. The agent was on Paul in a flash. DiCaro had just enough time to stand up before the first blow landed.

“You lied to me, gringo mother—-,” the agent shouted. “You lied to me twice.” Then he swung at Paul’s head. DiCaro tried to back up but a Federal had moved behind him and there was suddenly nowhere to go. The blow slid off the American’s ear.

“Wait a second… ” As Paul recounts the story, he tried to talk through the pain ringing in his head, and as he did so, the agent swung a foot at the gringo’s testicles, threw a series of body blows and then another kick. “You can have it all. You don’t want to bust me …” The plainclothes agent hit Paul DiCaro in the middle of the face.

Deborah Friedman ran toward them. “Mi esposo,” she shouted. “Mi esposo. You can’t beat him like that.”

The agent laughed, took one more kick at DiCaro’s crotch and had the Federales chain Paul to the Volkswagen until a car could be sent out from Guadalajara to pick the Americans up. A black 1974 Lincoln Continental with a red light on the roof arrived three hours later. Paul was put in the back seat and two agents drove him south. Debbie followed without handcuffs in the VW, driven by a third agent.

The Lincoln carrying Dicaro stopped for a little excitement along the way. The car had been moving through the outskirts of Guadalajara at a fast clip when a Chevrolet passed them going even faster and cut them off. The agents were furious and began chasing the Chevrolet. After weaving through traffic for three blocks, the Lincoln caught the Chevy and forced it to pull over. The two agents drew their .45’s and got out of the car. One grabbed the Chevy’s driver by the collar and the other put a pistol to the driver’s head. They said he ought to learn some respect. The driver protested, pulling the arm of his jacket down and showing them the insignia on his khaki shirt. He was a Federal, too. The plainclothesmen said it didn’t matter. He still ought to learn respect. They slapped him a few times before returning to Paul. The rest of the trip was uneventful.

At 4:45, the Lincoln Continental pulled into the garage under the Palacio Federal, the center of law enforcement in the state of Jalisco, in downtown Guadalajara. As soon as Debbie arrived in the VW, the agents took them both to the sixth floor, where they were told they would be interviewed as soon as Captain Salinas returned from dinner. That took three hours.

In the meantime, Paul and Debbie waited on a bench with no idea of what would happen. Their legal knowledge, restricted to high-school civics and TV cop shows, had hardly prepared them. They would not be allowed a phone call for a week. Their requests for a lawyer were ignored until after they were interrogated twice. They would not be fed for four days, and then only because another prisoner shared some beans her mother brought on visiting day. The interrogation began at 8 P .M., and it set the tone for what was in store. DiCaro and Friedman were not shown any identification by their interrogator but they are certain that he was called Captain Salinas, though Mexican authorities whom I have since queried now insist that there is no such captain.

The captain was sitting behind his desk when DiCaro was brought into his office. He motioned for Paul to sit. Two agents in plainclothes stood at parade rest behind Paul’s chair. One held a two-foot-long hard leather baton. Throughout the interview, he twisted the leather in his hands, and it made a high squeaky sound behind the American’s left ear. Salinas toyed with the edge of a folded newspaper on his desk. The captain wanted Paul to explain the marijuana.

Paul asked for a lawyer instead. The captain refused. Paul asked for an interpreter from the consulate. The captain said it wasn’t necessary. Paul asked for a phone call, and Salinas smiled.

The agent on Paul’s right bent over and suggested he ought to get on with his story. The captain was a busy and very important man. DiCaro took the agent’s advice and didn’t ask for a lawyer again until Salinas closed the Interrogation by sliding a piece of paper across the desk. This was Paul’s statement and the captain wanted him to sign it. The paper was typed in Spanish on both sides. DiCaro understood only every 10th word.

“If you don’t mind,” Paul explained in a polite voice, I’d like to have my lawyer read it before I sign.”

As soon as the words were out of DiCaro’s mouth, the room filled with tension. The agent on Dicaro’s right bent over nervously and advised signing right away. The agent on his left increased the volume of his leather squeak. After an appropriate pause to let the enormity of the moment sink in, the captain proceeded to teach Paul DiCaro the rules of the game. He opened the newspaper in front of him and revealed’ a .45-caliber Colt automatic pistol. The captain placed his palm on the weapon and turned it until the barrel pointed straight at Dicaro. Paul stared. With a slow motion of his thumb, Salinas drew the Colt’s hammer back. Paul DiCaro reached forward, took the pen off the desk, and signed his name. The captain smiled and said he had to sign both sides. Paul Dicaro smiled and signed his name a second time on the back.

DiCaro and Debbie Friedman were quickly learning the workings of Mexican law. It and the Yankee variety are built on different principles. The theory behind Mexican Justice is the Napoleonic Code, a legacy from the reign of Emperor Maximilian in the 19th century. Under this form of legal organization, the accused are, in effect, assumed guilty until they prove their innocence. There ls no effective Bill of Rights, and arrest is the equivalent of Indictment. There are no juries, and trials are not usually open to either the general public or the defendants themselves. The Judge decides largely on the basis of the case description written by his own secretary. Lawyers rise to be secretaries and secretaries eventually become judges. Legal business Is conducted in very small rooms, and there are no verbatim transcripts of the proceedings.

The daily application of the Napoleonic Code is shot full of mordida, the home-grown expression signifying the practice of gaining influence or getting results through bribery. Whom your lawyer knows and what his friends will do for you are as important as the law itself. Those who have risen to high position expect their assistance to be rewarded in proportion to their stature. The result ls mordida. Lawyers who know the judge or his secretary are in great demand and figure the price of bribes into their fees.

There are thousands of tiny passageways through the legal maze built by Napoleon and mordida. But these passageways were invisible to Paul and Debbie, whom Salinas ordered off to the city lockup. On the arch over its front door are inscribed the words Procuraduria de Justicia, literally translated as, “where justice is procured.” The sign means exactly what it implies.

It was 30 degrees in Guadalajara that night, and the jail was cold. There was no food. On the women’s side, Debbie was able to borrow a blanket. On the men’s side, Paul slept in a T-shirt on the floor. Both felt they were being buried alive and prayed that someone would rescue them.

On Friday night, Jan. 23, DiCaro and Friedman had a visitor. They had no idea how he knew they were there. His name was Hale, and he was a representative from the American Consulate. He patiently explained that his job was to help them get a lawyer, contact relatives in the United States and help arrange for them to receive money from home. Nothing more. He had no advice to give and no influence to wield on their behalf. Hale produced a list of Mexican lawyers and asked Paul to choose three of the unknown names. The consulate would contact their choices directly.

Blindly, they selected Gustavo Ramirez Gomez. If they hadn’t been such newcomers to Mexican justice, they never would have hired him. Gustavo Ramirez’s mordida was minuscule. He’d begun life as a campesino, a peasant; after the family farm was foreclosed, he moved to the city to work as an auto mechanic. Gustavo Ramirez learned the law at night school. He was full of resentment for the system and the way it worked. Ramirez was a very principled man who believed the law was the law and ought to be bigger than anyone who practiced It. He wanted $1,000 to take the case, to be paid when they were released.

Paul and Debbie hired him because he looked straight in their faces and seemed to know his business. Small mordida or not, Gustavo Ramirez was a smart attorney. He was the first to tell DiCaro and Friedman about Articles 524 and 525 of the Federal Penal Code. These provisions established a legal classification of marijuana “addicts” who trafficked for use only. According to Articles 524 and 525, possession of up to 40 grams is considered an addict’s habit and constitutes grounds for dismissal of criminal charges. Ramirez recommended pleading addiction and would approach the judge with this argument immediately. He was sure the charges would be dropped without a hearing. Gustavo Ramirez assured them, optimistically, that the process would take no more than 72 hours.

Ramirez was wrong. Seventy-two hours later, Paul Dicaro and Deborah Friedman were still In the lockup. Ramirez apologized for their disappointment and explained that the judge was about to be promoted and didn’t want to jeopardize his possibilities by seeming to be lenient on gringo marijuana addicts. They would have to wait for a formal hearing In two weeks. Paul and Debbie winced, tried to stifle their panic and buckled down for their wait.

One full week after the arrest, the two Americans were transported to the Jalisco State Penitentiary, outside Guadalajara. The prison was In an uproar when they arrived and soldiers were patrolling the grounds. The army had reinforced the prison guards after a daring breakout the day before. Six political prisoners had killed two guards with pistols and gone over the front wall. A bus with sandbagged windows had been waiting for them and raked the front of the prison with automatic-weapons fire. Two more· guards died on the front steps.

The Jalisco State Penitentiary didn’t feel much like home, but Paul and Debbie recognized it was going to be just that for another two weeks at least, if Gustavo Ramirez was right. DiCaro and Friedman didn’t want to think about how long they’d stay if Gustavo was wrong a second time. The car dropped Paul at the main entrance and Debbie around the comer at the women’s gate.

The walls at Jalisco State Penitentiary are 20 feet tall and four-feet thick. Built in 1926 to hold 1,500 prisoners, it now houses more than 3,500. Twelve blue-shirted guards walk the wall with carbines during the day and the shift doubles at night. The women’s section is a small compound. 90 by 150 feet, housing 100 prisoners. With the addition of Deborah Friedman, 3 of them were American citizens. Jane Barstow (like all the names of American prisoners described here, except those of DiCaro and Friedman, this ls a pseudonym) had been arrested for possessing 200 seeds In her car. She would end up staying four months and spending $4,000 to get out. The other American citizen, Elaine Gavin Sanchez, was married to a Mexican who’d been arrested on kidnapping charges. Elaine knew nothing about it but was arrested anyway. At the Palace, she said she was strapped to a table while a Federal interrogated her with applications of an electric cattle prod to her breasts, vagina and rectum until she passed out. Like everyone else, the American women spent their days wandering around the central compound at night, they were locked into one of four large sleeping rooms. Only half the women had beds and the rest slept on the floor. Debbie, Jane and Elaine slept on the floor. No one would sell them beds.

The Men’s Prison takes up the rest of the penitentiary’s 15 acres, except for the administrative offices and the separate political compound. The Men’s Prison Is more like a village with a population of 3,400. It has a soccer field, rubber factory, basketball court and a dozen assorted shops and cafes. On the night they arrived, Paul DiCaro met the prisoner who owned Javier’s Cafe, which ls between the mess hall and the front office. Javier befriended the American and told him Jalisco State Penitentiary’s first commandment. “Con dinero baile el perro“-with money, even the dogs will dance.

The Men’s Prison takes up the rest of the penitentiary’s 15 acres, except for the administrative offices and the separate political compound. The Men’s Prison Is more like a village with a population of 3,400. It has a soccer field, rubber factory, basketball court and a dozen assorted shops and cafes. On the night they arrived, Paul DiCaro met the prisoner who owned Javier’s Cafe, which ls between the mess hall and the front office. Javier befriended the American and told him Jalisco State Penitentiary’s first commandment. “Con dinero baile el perro“-with money, even the dogs will dance.

Javier knew what he was talking about. Every male prisoner at Jalisco State sleeps in one of six sections according to the state of his finances. A single cell in Department 6 costs a flat fee of $25. Department 5 rises to $45 and Department 3 on up to $75. Department 4 ls simply called “H” and, at $100 ls the last of the flat-fee cell blocks. Department 1 and 2 have 18-by-18-foot cells with 18-foot ceilings, arranged into suites, and rent by the month. Half of the prisoners can’t afford a cell and sleep in the hallways in either Departments 5 or 6, where they pay an appropriate “street fee” to the inmate “street sergeant.” The street sergeant takes a small piece of his rents and passes the rest on to the department captain, also an inmate. The six department captains take another small cut and deliver the remainder to what is called the prisoner jefe, or boss, Don Calistro, an old man doing 27 years for cattle rustling. This jefe keeps a herd of cattle inside the walls in a corral he himself rents from the warden.

Paul Dicaro began his stay in prison sleeping on the floor of Department 5. He explained to the sergeant that he had money on its way from the United States and would pay his fee when it arrived. After four days, the money hadn’t come and DiCaro was transferred to the floor in No. 6, the second worst. (The worst is the Pit, to which a prisoner is sent as punishment. The Pit’s ceiling is 4½ feet high and its residents are chained to a floor that the guards slosh with water every two hours. After one miserable night on the street in No. 6 listening to the sounds of 400 very poor people creeping around in the dark looking for something to own, Paul DiCaro knew he was going to have to get some credit right away. To do that, he would have to talk to Don Calistro, the jefe.

Don Calistro wasn’t exactly. suffering. He kept his cattle down by the soccer field and sold them to the prison butcher shop, which he also ran. The shop in sum supplied the mess hall, the cafes and the restaurants, one of which was Don Calistro’s. He had a handsome suite where he lived with his wife and children. Paul DiCaro approached him there on Feb. 3, the 13th day after his arrest. He told the Jefe that the money was sure to come. Don Calistro relented and DiCaro moved back to No. 5. Two days later, a money order arrived from Paul’s brother in Chicago. Paul DiCaro paid his debts and bought a cell in H right away. It had showers and toilets. Six.of the 10 other Americans in the Men’s Prison lived there.

Like DiCaro and Friedman, the rest of the Americans in the Jalisco State Penitentiary were small fish. Throughout the 1970’s, the United States has applied heavy pressure on Mexico to stop drug traffic. Good enforcement statistics have been rewarded with financial aid and gifts of equipment. The result has been thousands of arrests and an increase in traffic. The major dealers who move marijuana by the ton and 90 percent pure heroin in kilo lots are rarely arrested. They have the requisite cash for some very heavy mordida. The small fish are used to fill the statistical breach. Once he had met some of these other Americans, Paul realized just how lucky he and Debbie had been.

Mort Brainard was the only one besides Paul who didn’t tell stories about having been tortured. Brainard and his wife had been busted at the Magdalena aduana. The Federates found 4½ kilos of marijuana in the car and, Mort said, stripped his wife naked on the spot. He was told she would be raped if he didn’t sign a confession.

Bill Frye and Sam Russell had been arrested in the cab of a truck hauling 300 kilos of marijuana. The two Americans said they were chained to a tree at the scene of their arrest for two days and beaten at regular Intervals. When they finally reached the Federal Palace, they were cattle-prodded around their genitals, beaten with clubs and immersed head first In a 50-galIon drum of water. Frye is sure his testicles were permanently damaged. Originally sentenced to two decades apiece, $30,000 in bribes and legal fees had reduced their terms to eight years.

The Patterson brothers, James and Dennis, were awaiting sentencing for marijuana transportation. James had been worked over so viciously at the Palace that he almost died; his interrogator had beaten on his chest with a mallet and split open his rib cage. He was never hospitalized.

Robert Gordon’s questioning was conducted by the usual team of four Federales in a room right off the Federal Palace parking lot and lasted 30 days. He reported being given the full treatment of water, cattle prods and clubs. Gordon was originally arrested when the police kicked down the door of his Guadalajara apartment. They were looking for cocaine. No cocaine was ever found, he said, but he was charged with selling it nevertheless. His confession was signed after the interrogating officer placed a loaded .45 against his head. Gordon had been in the prison for three years.

No one was worse off than Alan Cummings, who had been caught with LSD. This seemed especially infuriating to the Federales. Two months after they were through beating him, a tumor had begun growing on the back of his head. In prison more than two years, he had once been hospitalized for a week but only after he had passed out on the floor of his cell and seemed to be dying and the rest of the Americans pooled their cash and bribed the jailer to take Cummings to the infirmary. Alan was married to a Mexican woman who came to sleep with him every two weeks and she was pregnant. He seemed to be slowly dying in the Mexican prison, yet had never even been sentenced. The other three Americans there were not well known by the rest.

Frye and Russell had bought a three-room suite for $500 when It had become clear that they were going to be in Jalisco State for some time. It was one of H’s nicest. During his first few days In that department, Paul spent a lot of time there, listening to their stories. They explained that there were no guarantees even mordida would work. One American arrested for possession of a marijuana cigarette had spent $10,000 over the last year and was still inside Santa Marta prison. All the Americans told stories about their countrymen. One was of an American citizen named Hernandez from Tucson, who had been giving the Guadalajara jailers a hard time, and they were said to have administered a fearsome beating with their leather batons. Two days later, on Christmas Eve 1975, Hernandez was rumored to have died from his injuries. Paul DiCaro soaked up the talk, and felt worse with every story.

He and Friedman next saw each other on the regular day when the women were allowed to visit the men. The couple walked across the plaza outside H, and Debbie shuddered as her eyes fell on the Snail, a Mexican prisoner who had tried to commit suicide by jumping off the two-story administration building. He had failed and only broken a leg. Rather than set the bone, the prison authorities amputated it above the knee. The Snail couldn’t afford crutches, and he made his way through the dust by pulling himself along with his arms.

The two Americans’ hopes for the judge’s hearing on Monday, Feb. 9, fell flat. The judge was unwilling to do anything more than reduce the charges. He said he needed more evidence about their addiction. Ramirez apologized for this further disappointment and delay but reassured his clients that it would be only a short while before they were freed. Paul and Debbie had their doubts.

So did Hannah Friedman and Tod Friend. Tod Friend is a member of DiCaro’s and Friedman’s Sonoma County co-op and shares their house. Hannah Friedman, Debbie’s mother, is a housewife in Waukegan, Ill., with a long history of community service. At this point, they joined forces to try to rescue Paul and Debbie. Before they were done, $10,000 had been spent, in bribes, lawyers’ fees and expenses. Relative to the sums paid by other Americans, it was a bargain basement.

As soon as Debbie’s mother had heard from the consulate, she had wired money and guaranteed the lawyers’ fees. She and her husband, a suburban physician, had flown to Guadalajara and visited the couple on Sunday, Feb. 8. Hannah Friedman had been so sure of Paul and Debbie’s Imminent release that she left them two plane tickets home, told them to stay out of trouble, and flew back to Chicago that night. When she heard that her daughter was still behind bars, she felt Debbie and Paul were being swallowed in legal quicksand. She wasn’t sure what to do .

Tod Friend had heard that it was possible to call the prison directly and talk to an inmate. He did and got Debbie on the phone. She said things did not look good. Friend called Hannah Friedman, told her he was going south and promised to call her from Guadalajara.

He rented a room In the Hotel San Jorge and began visiting Paul and Debbie every day he could. Most of the visits took place in a small room in the front of the prison, but on two days a week he was allowed to be locked in the men’s side with Paul all day long. Paul figured they needed a new lawyer. He liked Gustavo Ramirez but thought he was too naive and didn’t have the necessary connections. Paul had a replacement in mind: Francisco Gutierrez Martin.

Gutierrez Martin was said to be a legend behind the walls of Jalisco State Penitentiary. Martin’s extraordinary influence grew out of a long career teaching law at Guadalajara University. Three of his former pupils sat on the Jalisco State bench, and the old professor was said to be making great sums of money. Paul had seen one example of Martin’s influence first-hand. Two 17-year-old Mexican kids had been brought to the prison after being arrested while harvesting an entire field of marijuana. They were cocky and bragged that Gutierrez Martin was their lawyer so there was no reason to worry. Two days later, the kids were released. Many people told Paul that he and Debbie would have been home by now if they had hired Gutierrez Martin. Paul was convinced and sent Debbie a message to call Martin, who said he could, Indeed, get them out. It would cost $12,000 cash in advance.

Twelve thousand dollars in cash is a lot of money, and it took five days for Tod to persuade Hannah to bring it down. When she finally arrived in Guadalajara, Mrs. Friedman planned to see Martin and make the arrangements as soon as she had registered at the Hotel Fenix. She would have if there hadn’t been a sudden change in plans. At the last minute, Paul and Debbie decided to stick with Gustavo Ramirez. The change of heart grew out of a conversation with an imprisoned lawyer In Javier’s Cafe while Tod was spending the day. The lawyer’s name was Abraham and he agreed to look Paul and Debbie’s papers over. Abraham concluded that it was a waste of money to hire Martin.

“Gustavo has done all the work,” Abraham explained, “so why Martin?” The prison lawyer said the charge reduction was a first step to freedom and told them not to worry. Gustavo had all the right law on paper.

Tod reached Hannah with the news after she had contacted Martin and made an appointment. She called Martin back, canceled the appointment and deposited her $12,000 certified draft, on a Waukegan, Ill. bank, in the hotel vault. The decision saved money but would eventually cause Paul and Debbie plenty of trouble. The smell of cash was around their case now and a lot of folks in Guadalajara have a nose for the smell of cash.

In the meantime, Gustavo Ramirez put the final touches on their case. Friends of Paul, Debbie and Hannah in the United States sent letters asserting that the couple were genuine marijuana addicts and had been treated for their addiction for years. The last piece of the puzzle was their official certification. To get this, Paul and Debbie were taken out of the prison to a clinic near the Federal Palace. They both passed the examination with flying colors.

The other Americans had clued Paul in that the tests picked up traces of marijuana resin in the mouth and on the fingertips. Their mouths and hands would be rinsed with a solvent to collect samples. On the recommendation of his countrymen, Paul bought a little weed on the plaza and smoked half a joint on the morning of the tests. He hid the remainder in his pants and passed it to Debbie on their way to the clinic. She asked to relieve herself before she saw the doctor and smoked the rest of the weed in the bathroom. The next day, Dr. Natzahualcoyotl Ruiz Gaitao sent a memorandum to the Third Judge of the Distrito en el Estado certifying that the accused Paul Francis DiCaro and Deborah Lee Friedman “are habitual drug addicts in the use of marijuana … requiring at least three to six cigarettes a day.”

With that document, Gustavo Ramirez was ready to go back in front of the judge.

A few days after Gutierrez Martin’s aborted contact with Hannah Friedman, Ramirez began to encounter signs of Gutierrez Martin’s continued presence. Martin had evidently not lost interest in the possible $12,000 fee.

Gustavo was worried. He explained that Martin and the judge’s secretary had been talking. Ramirez had picked the story up on the courthouse grapevine. Martin was said to have told the secretary that the DiCaro and Friedman case had money attached to it, and that if it could just be held up until the Americans changed lawyers, there could be $400 in it for him. The news of Martin’s presence had left Gustavo Ramirez ready to quit. He thought·he ought to leave the case. Martin was impossible to fight.

The Americans disagreed. Hannah and Tod wanted to know why Gustavo didn’t just take $800 to the same secretary. Gustavo said they shouldn’t need a bribe. They were clearly in the right under the law. The Americans agreed but said they’d rather see Paul and Debbie free. Ramirez responded that it was exactly this mordida that had made Mexican law a joke, and he wanted no part of it. Gustavo Ramirez was a man of intense belief. He refused to eat meat because It symbolized the fat Mexico of the cattle barons. He refused to drink soda pop because it symbolized Mexico’s addiction to the Yankee Coca-Cola culture. Gustavo kept a photo of Che Guevara over his file cabinet. It took Tod and Hannah half an hour to change Ramirez’s mind about bribing the secretary. Finally, the challenge of beating Martin and his desire to get Paul and Debbie released overwhelmed Gustavo’s reluctance. The bribe was offered immediately and consummated with cash during the next week. On the morning of Friday, Feb. 26, 1976, the judge signed the documents dropping criminal charges. Gutierrez Martin subsequently denied any involvement in the case.

The Americans disagreed. Hannah and Tod wanted to know why Gustavo didn’t just take $800 to the same secretary. Gustavo said they shouldn’t need a bribe. They were clearly in the right under the law. The Americans agreed but said they’d rather see Paul and Debbie free. Ramirez responded that it was exactly this mordida that had made Mexican law a joke, and he wanted no part of it. Gustavo Ramirez was a man of intense belief. He refused to eat meat because It symbolized the fat Mexico of the cattle barons. He refused to drink soda pop because it symbolized Mexico’s addiction to the Yankee Coca-Cola culture. Gustavo kept a photo of Che Guevara over his file cabinet. It took Tod and Hannah half an hour to change Ramirez’s mind about bribing the secretary. Finally, the challenge of beating Martin and his desire to get Paul and Debbie released overwhelmed Gustavo’s reluctance. The bribe was offered immediately and consummated with cash during the next week. On the morning of Friday, Feb. 26, 1976, the judge signed the documents dropping criminal charges. Gutierrez Martin subsequently denied any involvement in the case.

The news reached DiCaro around 10:30 A.M. He wasn’t expecting it. Paul Dicaro had begun assuming that nothing would work out and was preparing to serve five years and three months, the minimum sentence for drug-related convictions. On Friday morning, DiCaro was all set to play third base In a prison baseball game. One of the young boys who hung out on the plaza brought Paul the message. He thought the American’s freedom papers had arrived. Paul tipped the kid a peso and hurried to the prison building, where a guard told him to go back to H and get his stuff. Paul DiCaro was being released. Debbie was given the same news on the women’s side half an hour later. Then they waited. The guard said it was only a matter of signing some final papers. Paul sat in the visitors’ room for three hours. During that time, Tod, Hannah, Gustavo Ramirez and Ramirez’ son Carlos arrived to welcome them out. They all waited together. When the guard finally gave Paul his release certificate and official papers, there was great jubilation. ‘The rescue team was laughing when they left to pick up Debbie.

The laughter came to an abrupt halt as soon as they walked out the front door. Two agents from the Department of Population were waiting on the steps. The Department of Population’s jurisdiction includes foreigners inside Mexico. The agents approached Paul and explained that before his release was final, there were some more papers to sign downtown. Paul was stunned. The agents handcuffed him and hustled him into their waiting automobile. The rescue team tried to follow the car but lost it shortly after the agents grabbed Debbie at the women’s gate. None of the rescuers had any idea where Paul and Debbie were being taken. Once again, Paul DiCaro and Deborah Friedman had disappeared into the morass of Guadalajara law.

Gustavo Ramirez’s best guess was that they’d been taken to the city jail, and the rescue party drove straight there. The lawyer went into two different offices to inquire and was told that there were no Paul DiCaro and Deborah Friedman in the city lockup. Gustavo was headed back to the car when he spotted a policeman friend of his In the hall. The friend assured him in confidence that he had seen the Americans in the building not 10 minutes earlier. Gustavo came back to Tod and Hannah looking angrier than they’d ever seen hlm. He said he was going tb find the judge and would drop them back at the Hotel Fenix.

Gustavo’s friend had good information. Paul and Debbie were in the basement sharing a cell. For the last 36 days, DiCaro had prided himself on his composure but that was all behind hlm now. Paul and Debbie had quickly perceived that all the talk about signing papers was a hoax and Dicaro was furious. He spent three hours kicking the door and screaming about all the rotten chicken— cabrones who had kidnapped him. He screamed down the hall that he wanted to talk to someone, goddamn it. No one came until 11 P.M. By that time, DiCaro had calmed down and he and Debbie were In their sleeping bags on the cell floor.

The visit was from Senor Gabriel Romero Barragan, the head of the Department of Population of Jalisco. He identified himself by flipping out a gold badge with papers and a photo. Romero stood on the other side of the bars flanked by two bodyguards.· He had evidently just come from dinner. One of his bodyguards reached up and wiped a spot of enchilada sauce from his lapel.

“Buenas noches,” Romero began. He understood the whole case, he explained In English, and he knew that the two Americans had their freedom papers, but that didn’t matter. Under the law, the Department of Population had the authority to hold them for 30 days before deportation. If, on the other hand, their friends were to make an arrangement with him, Romero could sign their deportation papers immediately and put Paul and Debbie on a plane. He gave the couple a scrap of paper with his phone number on it. Romero said he would instruct the jailer to give Paul and Debbie two phone calls the next morning. They should call their people and have them contact him directly. He would be in his office between 9 and noon.

“Tell them to bring their best offer,” Romero added with a smile.

Paul and Debbie were ready to pay whatever it took. They knew that if they weren’t released by Saturday at 6 P .M., all the legal machinery would shut down until Monday. By then every jackal in Jalisco would be onto their case and they’d be buried in payoffs. Feb. 26 was the worst night the couple had spent in jail. Their prospects seemed miserable.

As lt turned out, they had seriously underestimated Gustavo Ramirez. Ramirez was not about to be walked on by Senor Romero, head of Population or not. Ramirez found the Judge coming out of a movie at close to midnight. He explained what had happened and pointed out that Population had no legal authority over DiCaro and Friedman. The charges had been dropped so no deportation was in order. Population was totally out of bounds. Not only that, the lawyer argued, it was an obvious insult to the judge himself. When a judge ruled, it was final, and Population shouldn’t think it could overrule him. The judge agreed, and called his secretary. Instead of meetIng Romero the next morning, Ramirez huddled with the judge’s secretary. The incentive of another $800 cash for “bail” was enough to persuade the secretary to accompany him to the Palace and file charges against Romero and everyone else Involved in the two Americans’ illegal detention. They arrived at the Guadalajara lockup’s main desk at 11 A.M.

The secretary threw six different files full of charges on the counter and demanded the immediate release of the Americans, DiCaro and Friedman. The act drew a lot of attention. Secretaries to the judge of Distrito en el Estado do not visit a prison lockup except on very special occasions. The first clerk took one look at the secretary and the papers and called his superior. The superior approached the papers with a smile but lost it as soon as he began leafing through them. He retreated to the phone and called the Weasel. The Weasel was the lockup’s resident legal expert. He had a thin face and a long twisted nose that had a tendency to twitch. It twitched a lot as he read through the files. The Weasel got back on the phone and made calls for the next hour and a half. During the last and longest of them, he did little but listen to a loud Spanish voice and answer “si” and “no si“. After hanging up, the Weasel called down to the cell block and told them to send the two Americans up.

Like every other process they’d been through for 37 days, this last one took some time. Paul and Debbie had to wait half an hour at the cellblock door. The turnkey explained that he was on his lunch break and couldn’t open the door until he was done. They watched him eat burritos until Debbie started pulling her hair and screaming. The jailer finally opened up and went back to eat his lunch in peace. Paul and Debbie waited another three and a half hours in the front office while Gustavo, the judge’s secretary and the Weasel shuffled papers and signed documents. At 5 P .M., Paul DiCaro and Deborah Friedman walked out the Federal Palace’s front door. After 37 days behind bars, the late afternoon Guadalajara streets felt electric.

Like every other process they’d been through for 37 days, this last one took some time. Paul and Debbie had to wait half an hour at the cellblock door. The turnkey explained that he was on his lunch break and couldn’t open the door until he was done. They watched him eat burritos until Debbie started pulling her hair and screaming. The jailer finally opened up and went back to eat his lunch in peace. Paul and Debbie waited another three and a half hours in the front office while Gustavo, the judge’s secretary and the Weasel shuffled papers and signed documents. At 5 P .M., Paul DiCaro and Deborah Friedman walked out the Federal Palace’s front door. After 37 days behind bars, the late afternoon Guadalajara streets felt electric.

The party celebrated in the Hotel Fenix dining room. Gustavo was paid his $1,000 plus a $1,000 bonus, and put the dinner celebration on his tab. He wanted Paul and Debbie to stay in town to testify against Romero, but Paul, Debbie, Tod, and Hannah were ready to leave. Hannah suggested that they do so before Population had a chance to counterattack, and she devised a plan. The Americans made plane reservations departing the next day from both Guadalajara and Mexico City-then, in a rented car, they drove to Monterrey, changed cars and continued on to Texas. They crossed the Mexican border at Nuevo Laredo shortly after midnight on Sunday, Feb. 29. On their way to the San Antonio airport, the party stopped at the Alamo. It was 5 A.M. Tod, Paul, and Debbie kissed the monument’s wall.

At the airport, Paul bought a Sunday copy of The San Antonio Light. The front section was dominated by a two-inch banner headline: “U.S. Suicide in Mazatlan Jail.” The story, by Larry D. Hatfield, was about a young American jailed in the state of Sinaloa who had “committed suicide . . . rather than face torture for his part in an aborted escape attempt.” Paul DiCaro and Deborah Friedman didn’t need to read further. They closed the paper, boarded the plane to San Francisco, and counted themselves lucky to be north of the Rio Grande.

The Argument Over Mexican Justice

After repeated inquires made by The New York Times to various Mexican Government and U.S. State Department officials about the imprisonment case of Paui DiCaro and Deborah Friedman, the Mexican Government announced what was described as a change of policy: As of April 16, 1977, possession of small amounts of marijuana, cocaine and heroin for “normal use” would not be subject to criminal charges. However, those people already sentenced would have to continue serving their sentences, ranging from 5 to 14 years, and, in the case of marijuana, the announcement represented no change in the law. That provision already existed in Articles 524 and 525 of the Mexican Federal Penal Code, though, in fact, it was for possession of a small amount of marijuana that Dicaro and Friedman were put in prison. And reports of torture, mistreatment and corruption in Mexican prisons are still being heard from friends and relatives of the approximately 600 Americans in Mexican prisons.

The State Department’s statistics on the question are contradictory. At the June 29, 1976, hearings of the House Subcommittee on International Political and Military Affairs, Leonard Walentynowlcz, then administrator of the Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs, testified that the State Department had been able to substantiate 40 cases of physical abuse in the first six months of 1975 and 61 cases in the same period of 1976. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, however, in his quarterly report to Congress about the status of Americans in Mexican prisons on March 4 of this year claimed that only 58 cases had been substantiated in the entire period of July 1975 to January, 1977.

At present, the American and Mexican Governments are attempting to reach a treaty agreement on prisoner exchange, but it has stalled in the U.S. Senate on questions of constitutionality.

The Jalisco justice authorities deny DiCaro’s and Friedman’s allegations, and representatives of the Mexican Government and U.S. State Department contend that conditions have changed dramatically in the past year. Those with friends or relatives still in prison say the situation remains the same. Following are various comments on the matter:

“When someone is arrested, there are always complaints and bitterness. We always follow law and ethics. We live in a glass house and everyone can judge us. We are entirely satisfied and proud of our behavior.”

-Gabriel Romero Barragon, Chief of the Department of Population, Guadalajara, Jalisco.

“This is a typical case of Americans in Mexican prisons. If anything, these two were exceptionally lucky relative to the other cases that have come to my attention.”

-Representative Fortney Stark, Democrat, California.

“Usually, Americans are handled in a way comparable to their handling here in the U.S. We do have a substantial number of abuses, but once the case comes to the attention of the consular officer, nothing untoward happens. There has been significant improvement over the last year and a half and a marked decrease In reports of physical abuse. We have had innumerable discussions with senior Mexican officials and had a good response. It takes a while for the word to filter down, but we are begin_ning to see hopeful results.”

-Robert Hennemeyer, deputy administrator, Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs, Department of State.

“The State Department ought to come out of its ivory tower and deal with reality. Torture continues during arrest and interrogation. Things haven’t improved. Just this week, an American prisoner was in desperate need of an appendectomy and in great pain. They took her to the hospital in the back of a truck. That’s not torture? lt used to be that the consulate called collect but now they will return your calls at their own expense. That’s the biggest change. ln my experience, the consulate officials acted more like undercover C.I.A. and F. B. I. than consuls.”

-Juanita Carter, mother of an American prisoner in Norte Prison, Mexico City.

“Things have changed radically on this question. I’m almost in a position to say that you’re kicking a dead horse. Since the change of Mexican administrations, we have had almost no complaints of mistreatment. I suspect there is still a certain degree of extortion, but that lt, too, has decreased. We have developed a very good relationship with the Attorney General of the Republic on this question. We try to see that American prisoners have all the rights they are entitled to, but they are subject to Mexican law.”

-Rolfe Daniels, Chief of Citizen Consular Services, American Embassy, Mexico City.

“The State Department ls just a damn bunch of liars. Just last week, the new director of Santa Marta Prison allowed his cronies to extort all the Americans in his prison. They were told that they had to buy Insurance to keep themselves from getting hurt. They talk all about human rights In Russia but they don’t say a thing about Mexico. When the State Department says torture has stopped, they’re just not telling the truth.”

-Mildred Cottlow, mother of an American prisoner in Santa Marta Prison, Mexico City.

“Look very carefully into these people’s story. People who violate laws always see the story from their point of view, which may not be the whole truth. Sometimes law enforcers go beyond their prescribed limitations, but that often is dependent on the attitude of those arrested. By order of the President, these abuses have come to a standstill. Abusers have been dismissed and abuses are now in the process of being totally eliminated. We have always tried to investigate all allegations. When we have, we have often found the story to be more than the complainers told. Often it is shown that these people are drunk, resisting arrest, under the influence of drugs or have drugs in their possession.”

-Enrique Buj, Minister Counselor to the Mexican Embassy, Washington, D.C.

“I personally know of Individuals as recently as April 1976 who were tortured upon arrest. The treatment inside the Federal District prisons did improve over the last year. Two new prisons have been built. The arrest procedure, however, remained brutal as far as I could tell. Although the Federal District had Improved, the reports I heard from the provinces were still just as bad as ever. The judicial process hasn’t changed at all. In that sense, the prison reform ls a fraud. With the courts and arrest procedures unchanged, all it means is a nice place to stay after they screw you.”

-Bob Goode, American prisoner in Oriente Prison, Mexico City, released March 22, 1977.

Leave a Reply