Rolling Stone – 12/20/1973

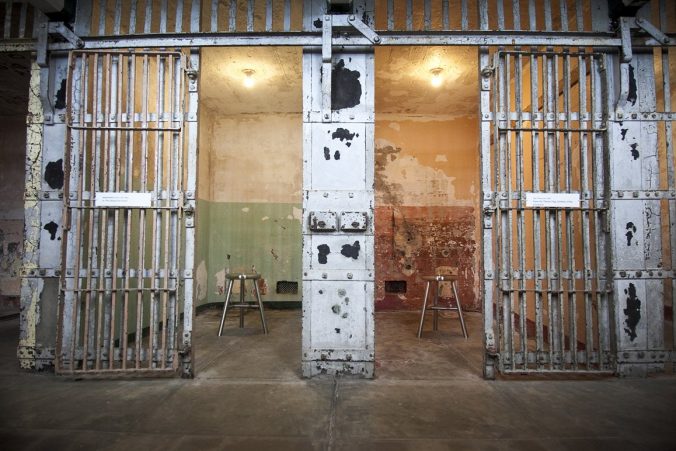

Living on Alcatraz was like living in a 50-gallon drum. There weren’t a lot of leaks and all the lives inside just rattled against each other and made echoes year after year. There was fog in the morning and two cell blocks, one man to a cell, 200 cells worth, standing by their bunks to be counted every second hour. And then there was the same all over again. Every tenth day, razors were issued. Every Wednesday and Saturday there was hot water for a bath. All mail was read by the police and retyped on Alcatraz stationery before it was delivered. For two hours a day, residents of the 200 cells got to hang around in a walled courtyard between buildings. Six rifles watched them shuffle back and forth. After awhile, life on Alcatraz did strange things to anyone who tried to live it.

The strangest Earl Johnson ever saw happened right after he got there in 1939. It was between two crime partners and best friends named Stanley and Jimmy Dee. They were still youngsters when they ran into 50 years apiece, head on, right after Jimmy Dee told the teller to push the money across the counter. The two of them lived on the bottom tier. Jimmy Dee caught a mouse and trained it as a pet He loaned it to Stanley one afternoon and Stanley accidentally flushed the rodent down the shitter. The crime partners didn’t talk the rest of the day. When the cop turned the lights, Stanley apologized and said good night.

“You better have a good night Jimmy Dee answered. Come morning, Stanley, you got no more nights coming at all.”

Stanley figured Jimmy Dee was talking jive, but he should have paid attention. When the hack opened the door for work call. the bank robber revenged his mouse. The two crime partners reached the hallway at the same time and Jimmy Dee stuck a homemade shank into his best friend’s belly and out the other side. The knife was a foot-long piece of steel, sharpened on one end. When Stanley reached hospital, his guts were leaking all over his pants. Watching the body made Earl Johnson want very badly to move. Stanley’s cold blue face convinced him that life on Alcatraz was a one-way proposition.

Not that Earl Johnson wasn’t used to it. His life had been that way for a long while. He’d started low and didn’t have a long way to fall when it came time to touch bottom. His earliest memory is the St. Peter Home for Children in Memphis. Tennessee. The orphans slept ten to a double bed, a hundred to a room. They shit in buckets and the older boys cleaned the drippings. The home lived on what the sisters could beg from the produce houses downtown. If you were ten or II years old, you spent the day cutting bad spots out vegetables. If you were six or seven, you watched the twos and threes. After 12 years, Earl decided to take a look at the world and went over the fence.

He ran from Memphis to Lascassus, Tennessee, and lived with a doctor’s family for seven years. Earl milked the doctor’s cows and got a room in exchange. In 1929, the doctor signed a note saying Earl was of age and he joined the army. To Earl, it was a way to beat the Depression … but Private Johnson never turned into much of a soldier. He was dishonorably discharged with the rank of private from the 28th Infantry in 1936. Once in civies, Earl had a career all staked out.

It was sort of a small business, Starting in Illinois and running as far south as Georgia, Earl bough US Government sub-machine guns from needy supply sergeants. He hauled the weapons to an alley behind a Chicago flower shop and unloaded them in rose boxes. His business made it as far as 1937 before the bottom dropped out. In August, Earl Johnson was charged with two counts of stolen government property. He was convicted and sentenced to three years in the custody of the Attorney General. At this point in history, without his full knowledge and none of his consent. Earl Johnson’s life began in earnest.

Between 1937 and 1973, Earl Johnson has been convicted of nine felonies and sentenced to 30 years in the penitentiary. Some of the sentences ran on top of each other and others ran end to end. All told, with good time taken into account, Earl spent better than 21 of the last 36 years in prisons. During those two decades, Earl Johnson was known by 12 different names. His first five were 4724, 6393, 56139, 58972 and 62268. On each of 21 Christmases, a guard gave him a paper sack full of hard candy, just like the sisters used to at the St. Peter home. Earl received his first letter at Leavenworth mail call in late 1949. He got his first visit for half an hour in 1962.

Those years show all over Earl Johnson. He’s 63 now and drags bronchial asthma, emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis and a case of diabetes with him wherever he goes. He figures to die soon. Earl remembers a lot of things, but they’re all framed in concrete with a gun tower on each corner. It’s not a lot to show for the time spent, but Earl Johnson will be the first to tell you that it’s all he ended up with. “I lost,” he says. “It’s like I was bound to from the start. I was born in the wrong place at the wrong time and never changed. I’m what you call a victim of circumstances.”

Earl never managed to help his own cause much along the way. From the day he stepped inside the walls, he had scabs on his knuckles and trouble on his young mind. The wails made his muscles twitch and he shivered. It was Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary surrounded with 40 feet of brick, stone and high-powered rifles. In those days, Lewisburg was a famously mean place, especially in the winter.

When the snow covered the yards, nobody was allowed outside. To get from one building to the next, you walked in underground tunnels. A certain etiquette was practiced in the tunnels that couldn’t be practiced any place else. If you met a guard all alone, you could kick his ass and he wouldn’t say a word. It worked vice: versa as well. Earl learned his manner quickly. Before March he’d seen his first killing.

Sam Dorsey, one of Earl’s paddy friends from Chicago, was at the middle of what happened. Dorsey had been jumped earlier by an old convict and fucked in the ass. He wanted blood back and took his friends with him to get it. They caught the old convict in the tunnel after lunch and beat him to death with their fists. Earl and five others were picked up on suspicion, but no charges ever stuck. In the meantime, they were all locked in the Hole.

The Hole was 12 cells, each five feet by seven feet with the toilet built into the floor. There was no heating, no bed and one blanket at night. It was five degrees outside and frost formed on the walls. Every day the Hole was fed a bowl of cabbage and carrot scraps and a half gallon of water. Every third day, they each got a meal from the regular serving line. After his 42 days in lockup, Earl got back to his bunk and was nothing but a little meaner for the experience.

That meanness sealed Earl’s future. By the next, winter he was back in the to Hole. This time it was a brawl in the dining room. Nobody was hurt in the fight, but one convict died of a heart attack while it was going on. Eighteen people from the center of the action were locked up and charged with manslaughter and conspiring to riot. Only Joe Lynch was convicted and he got 20 years. The rest were shipped to the far reaches of the prison system. They were labeled “dangerous” in their files now and had to be separated. Earl and six others were sent, to Alcatraz. On the yard it was called The Rock and was a legend to a minor-league thief like Earl.

The Rock was as close to the big time as he ever got. Starting in Alcatraz, Earl met a lot of people you read about in the papers. As little fame as his life provided, at least he got some household words to spend it with.

When Al Capone was moved from Alcatraz to Terminal Island, Earl was on his way west in a prison car. The biggest men left on The Rock were Alvin Karpis and Machine Gun Kelly. They had a comer of the yard all their own. Earl beard their names being whispered when he first arrived and it wasn’t long until he knew them himself.

He got to know Karpis best of all. They walked on the yard together. Mostly Karis talked about how scared he was of dying in prison. Whenever the thought crossed eyes, his head seemed to squeeze together. He wanted to die on the streets more than anything else. Karpis had good season to be worried. His sentence read “30 years” and the government seemed to mean it.

When he was still robbing banks with Ma Barker, Time magazine named Alvin Karpis “Creepy,” and it stuck. Creepy Karpis became Public Enemy Number One after he was linked to the kidnapping of a Minneapolis banker. The FBI chased Karpis for three years. Once he was cornered in Atlantic City and shot his way out. Seven months later he wrote a personal letter to J. Edgar Hoover and told him he’d blast his ass off if he got the chance. He never did. In May of 1936, Karpis was grabbed coming out of a New Orleans apartment house and never fired a shot. Hoover chartered a plane to personally haul Creepy back to New York.

“Karpis said he’d never be taken alive,” Hoover announced to the press, but we took him without a shot. That marked him as a dirty yellow rat. He was scared to death.” In those days, J. Edgar’s cheeks didn’t quiver when he talked. On the other side of the flash bulbs, he looked like a bear trap. The same week Karpis was busted, Hoover got his first raise from Congress.

Sometimes Karpis would lift his head into the sea breeze and talk about J. Edgar. Karpis said the name with a spit.

“The son of a bitch is a coward,” Creepy said. “A stone coward. He’s a pig and a sex pervert too. Look at him. He never got married and he lives with them young FBI agents. It don’t take a genius to figure that out. No sir, it don’t”

Earl Johnson didn’t stay on Alcatraz long. The associate warden decided his sentence was too short to stay in such a tight cage and promised to send him east with the train in the fall.

Needless to say, it wasn’t the Santa Fe Chief Earl got to ride. Now prisoners move in buses, but in those days it was the old style railroad car. They moved across the country in spurts, coming off sidings and hooking to the ass-end of anything headed towards Kansas. The car had a cage around each door for the hacks and the rest was benches where prisoners sat two across. Every pair was chained to each other at the wrist and leg; each man was chained again by himself to an eye bolt on the floor. They sat on top of all the railroad rumbles with one hand free to eat.

When the train first moved out, Earl was the odd man out and chained to himself. Rumor had it they were picking up another prisoner along the way. Sure enough; the train was met by an Oldsmobile half a day out of The Rock. The cop opened Earl’s cuffs and shackles and told him to make room. When the doors began clanking, a buzzing stated up and down the train. The guy behind Earl was a Chicago guinea. He poked Earl with his elbow.

“Hey Johnson,” he whispered. “They’re’ gonna strap you to Al Capone.”

Earl turned to look and it was true. There was the Big Man himself coming down. the aisle. He moved slow and his body rose up to his shoulders like two scoops of vanilla. He took the window seat.

It was late in 1939 and Al Capone’s syphilis had more or less fried his brain. He jumped at small noises and dribbled on his chin when he slept. Capone could still make sense in conversation, but he hardly talked to Earl. He just asked three times if Earl was going to try to escape. Capone was convinced the cops wanted an excuse to kill him now that he was close to the streets. He didn’t want Earl dragging AI Capone into a casket. Other than that, Capone talked to the guinea at Earl’s back.

“Hey, Mr. Capone,” the guinea said. “On The Rock, yard talk says you left a big stash of money there when they shipped you out.”

“Yeah,” Capone said, “about a hundred grand. The tide’s probably got it by now.” He stopped to think a minute. “Maybe,” he added. Capone stopped again and blew snot into the corner of the car.

“What’d you use all that bread for in prison?” the guinea asked.

Capone just laughed. He laughed with a great harumphing in his chest and a wiggle of his hands.

A day and a half later, the Big Man was taken off the tram and driven all the way to Lewisburg in a Ford. He left in the night at a siding. Two hours after Capone’s exit, everyone else was hitched to a freight and heading east.

“Leavenworth, Kansas,” the guard grinned, “next stop.”

The Leavenworth arrival and discharge clerk said Earl was just being laid over awaiting transport to the penitentiary in Atlanta. By the time he reached Georgia, Earl’s sentence would be used up and he’d be released.

“You won’t be here long enough to get in any trouble,” the clerk said.

He was wrong. Earl’s new trouble was started by a man named Robert Stroud. It was 1940 and Stroud wasn’t very famous. Later, when he’d been named the Birdman of Alcatraz, United Artists hired Burt Lancaster to play his part. In 1940, he was still just Robert Stroud in Leavenworth’s isolation cell block. He was known on the yard as a crazy son. of a bitch. Talk was that he’d killed seven men inside the walls and God knows how many outside. His sentence was to solitary confinement so not many got to see Stroud up close. The only time he was allowed out of his cell was for the Saturday afternoon movie. Before lights out, Stroud made his appearance with a guard on each side. The two screws took seats and then tugged Stroud down between them. Stroud stood up as long as be could and looked all over the room.

“He was scouting,” is the way Earl remembers it. “That’s what he was doin’ . Lookin’ for the young ones. He’d pick somebody he thought was pretty and wait for the lights to get turned off.”

With the movie on, Stroud made his slip. The guards knew Stroud was a lot less trouble all week if he could get his rocks off Saturday afternoon. They made it a practice to look the other way, Stroud crawled back under the benches to where Earl, Tommy Miller and a kid from Omaha were sitting. Earl looked down and there was Stroud on the floor. The Birdman reached up and popped a button off Johnson’s fly. Without a blink, Stroud started grabbing at the head of Earl’s dick. Earl Johnson jumped up and hit him across the face as hard as he knew how. Stroud’s head made a click and a crumpled sound as the fist landed. The swing broke Stroud’s jaw but that didn’t stop Tommy Miller. For good measure, Tommy put a size 10 D along the side of the Birdman’s head. Stroud moaned and the lights popped on. Earl and Tommy were sitting on the bench. Stroud was stretched out in a puddle of type O all over the floor at their feet. The hack saw skin missing from Earl’s knuckles and let him have the Hole for six weeks. When he got out, the Bureau of Prisons gave Earl .Johnson the ride to Atlanta they’d been promising.

There was only one short stop to make along the way. It was in Birmingham. Alabama, and it changed the trip considerably. The government hadn’t forgotten the charges they’d tried for and missed. With a little research they found one that wouldn’t. It was left over from the Thirties and carried three more years for $150 worth of stealing. The judge passed sentence on Friday, the 13th of September, 1940, and Earl made it to Georgia in time to start over. Instead of a release, there were 43 enclosed acres and 4000 men locked in six levels of cells. The only releases Johnson got to see for awhile belonged to somebody else.

Just one of those he watched broke out of the same old pattern. It was during World War II and involved the issuing clerk from the storeroom. His name was Earl Browder and he left like nobody else.

On the streets, Earl Browder was the head of the American Communist Party. Earl Johnson saw him regularly when he drew the hospital’s supplies. Browder always smoked a cigar the size of a small tree limb. He chewed on it and kept to himself. When he talked, it was about the War. Browder was convinced the allies would win with Russia fighting alongside. Earl believed him. He looked at the hospital records and learned that Browder had the highest IQ ever tested in Atlanta.

Browder was as bitter he was bright. He was serving a four-year sentence for using a fraudulent passport as identification. He was tried for his offense after the statute of limitations had run out. In the next trial after Browder’s, the same court heard an identical case involving a songwriter. The songwriter was given a $500 fine.

Browder’s release was strange in two ways. For a start, it happened on a Saturday. Earl Browder was the first man in Atlanta’s memory to be released on

a weekend. The second strange thing was what he got to wear. Everyone else was issued clothes from the storeroom. In Browder’s case, the Warden himself went downtown for a hundred-dollar suit. Browder’s release was a gesture to our Russian allies and the orders came from Franklin Roosevelt himself.

On the day Browder left, FDR announced he was cutting the Communist loose. Roosevelt said it would promote national unity and allay feelings in some quarters of political persecution.” Browder got in one of the limousines sent from the Russian Embassy and went back to Yonkers to help FDR win the War.

Winning the War was everybody’s job in those days. Even convicts. Atlanta Federal Penitentiary was put to work 12 hours a day, seven days a week, making canvas bags for the Army. It was sweatshop labor and jam-packed. There were 2000 more convicts than the institution plans called for and a lot of men slept in the factories at night. Food was rationed and bad. It finally got so bad the residents of Atlanta Penitentiary had to drop what they were doing and fight their own war first.

It started and finished with 4000 pieces of fish the kitchen tried to serve in 1942. All 4000 smelled like toe rot. Not a man would touch it. Talking got loud and some cons began to bang their spoons on the metal trays. That brought the cops from all over the institution. The warden led the charge. He was shown the fish.

“It’s good fish, goddamn it,” he said. “Call the doctor down here,” he told the lieutenant, “he’ll tell them.” Then the warden stood up on a table.

“You men listen to me,” he screamed. The warden had a great bull neck that was cheese-colored. “That’s good fish. And you’re gonna eat it. We’re gonna serve it and you’re gonna eat it. We’ll keep serving it until you do. As long as you don’t, no commissary privileges, no visits, no mail and nothin’ else on the line.” The warden jumped off the table but nobody ate. The doctor had arrived and examined the fish. He took the warden by the arm and led him off to the side.

“Be reasonable,” he said, “the men won’t touch this fish. They shouldn’t. My job is to keep these men healthy. Your job is to keep them here. They can’t stay healthy if they have to eat poison fish. I mean, would you eat it?”

“I goddamn sure would,” the warden said.

“I don’t believe you,” the doctor answered.

The warden scooped a piece of fish up and swallowed it in a gulp. Thirty seconds later, he puked all over the table and the front of his three-piece suit. The doctor took the warden up to the hospital and the cooks replaced the fish with beans.

The men of Atlanta won that battle, but it was one of a very few victories. Atlanta was a tight place and there were casualties.

Earl’s friend Poole was one of them. The cops busted Poole standing in the shower up to his belly in another man’s ass. Nowadays, he would have been moved to E cell block without anything being made of it. In the Forties there was a different policy. “Homosexuals” were taken to state courts and tried on sodomy charges. Sodomy in Georgia carried 30 years every time it came in front of the judge. As a service to the inmate, the institution notified Poole’s family of what he’d been caught at. The Friday before his mother came to visit, Poole snuck out of the basement and took the staircase to Number Five range. The cell houses were tiers on each wall with open space for five stories in the middle. Poole looked both ways, crossed himself, and launched a swan dive that ended head first on the cement roof of the basement. After he was scraped up, a prison truck took Poole to a mortuary downtown.

Earl planned to leave in a little different way. By I 943, his chance came. A notice was posted all over the institution. “All men who can pass a physical and mental test,” it read, “and aren’t serving sentences for heinous crimes are acceptable to the US Army. See the lieutenant for details.” Earl got six months lopped off his time and orders to report to a Memphis draft board. From there it was the Army again, but not for long.

Earl Johnson wasn’t any more of a soldier the second time than he had been the first. He was AWOL within a year and managed to stay free until 1945. Then a federal judge in Dallas gave him five more years for stolen government property and it was back down the line. This trip his orders were for Leavenworth. The Army mailed his discharge there in 1946.

Leavenworth in the late Forties looked just like Chicago in the late Thirties. Almost everybody who’d been anybody was there. Louis Lepke Buchalter had one on to New York to be electrocuted for his work with Murder, Inc., but Paul “The Waiter” Ricca, “Little New York” Campagna, Charlie “Cherry Nose” Gioe and Frank “Legs” Diamond were all still around. You might say they formed the institution’s upper crust.

The gangsters were an aristocracy by virtue of their money more than their reputations. They all had a regular source of cash on the streets and used it to buy away a few of the discomforts of prison life. Earl Johnson was in the hire of Charlie Gioe.

He and Cherry Nose worked in the out-patient clinic together. Gioe had $10 sent to Earl in the mail each month and Earl did Cherry Nose’s labor. For Earl, it was either that or have no money to spend at all. Working for Charlie Gioe wasn’t bad. He was tall and had a nose that stuck straight out of his head for what looked like miles. Gioe kept his prison clothes pressed into sharp edges but he didn’t look like a gangster. “He was too skinny,” Earl remembers, “and his face got all red-colored whenever he was pissed off. Looked more like a supply sergeant than a hood.”

Legs Diamond looked the part as much as Charlie Gioe didn’t. He shared a six-man cell with Earl in A cell house. Diamond was Capone’s brother-inlaw and thought of himself as something special. When Earl tried to’ make conversation, Diamond made a point of cutting it off.

“On the streets, I hire people like you as clerks for $30 a week,” Diamond said.

That was pretty much the way he got on with everybody. When it became too much for the other five men in the cell, they gave Diamond the blanket treatment. Frank fell asleep, a blanket was thrown over his head and his cellmates pounded on it with whatever was handy. When Diamond untangled himself and recovered, everybody was asleep and he couldn’t figure out who to have killed.

Little New York Campagna heard about what had happened and approached Earl in the yard. Campagna and Diamond didn’t get along. Little New York offered Earl some more work.

“I hear good things about you, Johnson,” Campagna said. “People say you know how to keep your mouth shut.”

“It’s sure enough the truth,” Earl answered.

“Well, me and my friends could use your help.” Campagna talked with one eye to the tower and the other on his three-cobblestoned bodyguards. “We’d

take care of you real nice if you were to make it so Frank Diamond couldn’t talk too well. Maybe you could make a vegetable out of him.”

It was tempting but Earl turned it down. “I tell you, Mr. Campagna,” Earl said. “I appreciate the offer, but I’m sick of doin’ time. Right now I want out more than I want to be taken care of.”

Campagna and his friends understood. As a matter of fact, they wanted the same thing themselves. With the help of their money, the gangsters beat Earl to the streets. The Chicago boys paid a hundred thousand dollars to T. Weber Wilson, a member of the US Board of Parole, and left before the Forties were up. When the payoff was later revealed at the Kefauver Hearings, T. Weber Wilson jumped out a window. Earl read about it in the papers.

Campagna and his friends understood. As a matter of fact, they wanted the same thing themselves. With the help of their money, the gangsters beat Earl to the streets. The Chicago boys paid a hundred thousand dollars to T. Weber Wilson, a member of the US Board of Parole, and left before the Forties were up. When the payoff was later revealed at the Kefauver Hearings, T. Weber Wilson jumped out a window. Earl read about it in the papers.

By 1948, Earl Edison Conateser Johnson was so sick of the penitentiary that his patience gave out. He hid all night in the garbage and rode with the potato peels right out the gate. The guard poked the load with a steel rod but never suspected. Earl stayed loose for 11 months. When he was recaptured, he went to the Special Treatment Unit for six months and lost all of his good time.

Earl’s attempt was just a little pissant try but he had a hand in one that became a legend. The escape came off in 1954 but Earl’s involvement dated from the early Forties. When he was in Atlanta, Earl found an old copy of the institution’s blueprints in the hospital files. Earl gave the plans to his friend Charlie Stegall and Charlie took it from there.

Stegall studied the plans for more than ten years. Then he got Bill Ellis to go with him. The two went out of Atlanta through an 18-inch storm drain in the middle of the baseball field. They stripped naked and dragged their clothes behind them on ropes. The pipe dropped 20 feet straight down and then ran 500 feet to the wall. By the time Stegall and Ellis inched the 500 feet, sewer rats had chewed their ropes away. The rats were big as cats and hungry. All the two convicts had left in their possession was a flashlight and their homemade bar spreader. The drain ends were crisscrossed with steel but the tool made a hole big enough to move through. The sewer came out in a creek after another half-mile of 36-inch pipe. When they reached it, Charlie Stegall and Bill Ellis were free and naked at the same time. Charlie solved that by robbing a clothes line. The only thing left in the plan was the pickup. A friend was bringing a car on Saturday. It was Wednesday so the two moved up the creek bank, found a cave, and waited.

In the meantime, the federal authorities were freaking. It took them a day to find they’d lost two prisoners and when they did, they had no idea how the two had left. The warden theorized a secret exit and expected that Stegall and Ellis were just the scouting party for a massive break. The institution was put on lockup and the Army was called in from Ft. McPherson. A ring of infantry and tanks surrounded the penitentiary. They waited.

All the waiting ended on Saturday with a hitch Charlie Stegall had never expected. It seems his pickup man had been indicted on 50 counts by the IRS since Charlie last talked with him. The driver spotted his chance and settled out of court. He took the federal attorney and a battalion of police to the creek bottom and they busted Stegall and Ellis in their stolen overalls.

They gave Charlie another five on top of his 35 and sent him to The Rock to do it. The government would have settled for his good time but he wouldn’t tell them how he got out. He never did and stayed on The Rock until it closed in 1963.

But that was a long time after Earl Johnson became a free man again.

Earl’s next bout with the streets began in 1951. He had to go through Arkansas to get there. The federal government released him to the custody of the state authorities. Arkansas had two years waiting for a dog-track robbery in 1944. Fortunately for Earl, the Arkansas authorities were reasonable men. He had two friends from St. Louis deliver $600 to the superintendent and left after six weeks.

“If you’re arrested before June of 1953,” he was told, “you’ll be considered an escaped prisoner.”

Earl Johnson took them seriously. He got a job with the New York Central as a brakeman and rode the rails for ten years. It made Earl feel good. He felt so good he got cocky. Earl started fencing stolen checks along the way and stopped one check too late. That earned him three more years with the Attorney General and a return ticket to Atlanta in August of 1961.

After a ten-year layoff, doing time didn’t come as easy. Earl’s body was starting to be a problem and he couldn’t keep the pace he once kept. He was suspicious and not without reason. For all his time in prison, every charge that Earl Johnson faced was brought with a snitch as a prosecution witness. It made Earl keep to himself. He had become his own kind of loner, talking only to the back of his head. That must have been what attracted him to Rudolf Abel. Abel was the same way.

In Abel’s case, it was by force of circumstance. Abel was an outcast. Earl was one of the few that would talk with him.

“They treated him worse than a motherfucker or a daughterfucker,” Earl recalls. “And a daughterfucker is the lowest thing in a prison.”

It all came from Abel being a spy. Rudolf Abel was a Russian Lt. Colonel who entered the United States with the name Emil R. Goldfus in 1948. Later he used “Martin Collins” when he felt he’d been compromised. He got a flat in Brooklyn and started sending signals to the Soviet Union. Colonel Abel made microfilm and left notes under a bench in the park. In 1957, one of the agents he controlled defected to the Americans and sent the FBI to Brooklyn. Abel got 30 years on three counts of espionage.

The Russian walked the yard a lot and Earl began to walk with him. After it had become a regular thing, Johnson was called to the warden’s office. The FBI agents were waiting with an offer.

“We understand you’re friends with Rudolf Abel,” the first agent said.

“Good friends,” Earl said back.

You should understand,” the second agent said, “because of his guilty plea in court, a lot of things about Abel’s operation weren’t cleared UJ?. We need that information and the government is willing to pay you to carry a small electronic device.”

“No,” Earl answered.

“You ought to consider that we’re in a position . . . ” ·

“No,” Earl interrupted. “I never been your snitch before and I’m not starting now. I ain’t gonna ‘ought to consider’ nothin’.”

The first agent rang for the guard.

Back on the yard, Earl told Abel about the agents. Then he told the Russian never to say anything about his work. “I don’t want to know none of that,” Earl said.

Abel trusted him. Rudolf was afraid to go to the sick-call line himself so he sent Earl to fetch what he needed. Abel worried about poison and knew Earl could get the pills straight from the doctor. The two were good friends until February of 1962. That’s the night the hacks came and got Abel.

They woke the Colonel up at two in the morning and told him to pack his shit.

“Where am I going?” he asked.

“You’re just going,” the cop said.

When Abel passed Earl’s bunk, Earl was asleep. Abel left a note on the blanket that Earl found in the morning.

“I don’t know where they’re taking me,” it read, “but I’m going. I’m being taken out of the institution. Goodbye, Rudolf.”

As soon as he read the note, Earl went to the bulletin board to check the transfer sheet. The transfer sheet is a mimeographed daily list of changes in any convict’s classification or status. Rudolf Abel was at the top of the page. Under final destination it said “on trip.”

When his Newsweek came in the mail, Earl found out that Rudolf had been exchanged with the Russians for U-2 pilot Gary Powers. Since then, Abel has retired and is rumored to be a national hero in the Soviet Union.

With Abel gone, the only people left at Atlanta to make news were the gangsters. Of those, Mickey Cohen had the worst luck. Mickey Cohen had been L.A.’s own, complete with hot women and Cadillacs. When Mickey came out of federal court, he had 20 years strapped to his future and moved to McNeil Island, Washington. That wasn’t good, but you couldn’t really call Mickey’s luck bad until he was transferred to Atlanta. Atlanta just about sewed things up for Mickey Cohen.

Mickey was a big man at first. He put talcum powder between his sheets and changed them every day. Mickey kept his blues starched and pressed and 30 convicts on his payroll. His luck left him when an Indian named McDonald from North Carolina tried to muscle in.

The Indian came up on the yard and stood between Cohen’s bodyguards.

“Say,” the Indian said, “I know you’re havin’ commissary money sent to a lot of dudes. You should know it would keep you healthier if you cut me in.”

Cohen looked at one of his boys . “This punk is muscling in. He’s trying to muscle in on Mickey Cohen!” Then Mickey turned straight on the Indian. “Nobody muscles Mickey Cohen, Hiawatha, and consider this your last warning.”

McDonald didn’t say anything more out loud. Behind his eyes, he decided to make a white man’s name for himself and walked across the yard.

McDonald knew he couldn’t get Cohen on the yard or at his bunk. The gangster’s boys were with him everywhere but work. Cohen was a clerk in the electric shop. While the Indian was trying to arrange to get there, he got thrown in the Hole. For a week McDonald sat and thought about it. Then the guard opening cells for showers forgot to lock the door when he left the block. It was all the chance the Indian needed. He went out of the cell house to a small yard, scaled an 18- foot fence and headed for the electric shop. Cohen was sitting at a desk reading the paper. The Indian put a lead pipe in the middle of the gangster’s brain. It didn’t kill Cohen, but L.A.’s own was a piece of cauliflower forever after.

Earl knew Cohen in the hospital when his luck turned sour. After Earl’s time was up, Mickey stopped drooling and said goodbye in sign language. Earl thinks he meant come by and see me when you’re in L.A. sometime.

By the time Earl got back again, Atlanta had a new generation of gangsters. They were the ones called Mafia. Come 1965, Earl took another three years for a stolen Buick and noticed the new faces right off. These Mafiosos were all over the yard. They were led by a man called Vito Genovese, but you couldn’t tell it by looking. Genovese kept no bodyguards. He was mostly quiet, but talking to him you’d think he was a priest. It was hard to believe he put the kiss of death on Joe Valachi, but that’s what Valachi said.

Nobody on the yard knew if Genovese had or not, but they knew something was up. The something turned out to be Joe Valachi. He was a little Mafioso. Joe kept getting called off the job to his caseworker’s office. Once there, he was talking to the government agents. Valachi wasn’t sure if anyone knew or not, but he was scared. He went to the associate warden and asked for protection. The AW put him in isolation for a week while the snitches found out if Valachi’s fears were justified. The snitches reported nothing was up, so the AW put Valachi back with everybody else.

Valachi said the AW was crazy. Genovese himself had administered the kiss of death. Valachi even knew how they were going to do it. Joe Beck was the hit man. Beck’s real name was Polombo and Valachi was convinced that Beck had been sent to the penitentiary with the express purpose of snuffing Joe Valachi. Even so, the AW wouldn’t listen. That made Valachi desperate.

Joe Beck was a mean son of a bitch and Valachi knew he didn’t stand a chance. He had to get out of population. He had to find a place where Beck couldn’t get to him. So Joe Valachi conceived a plan.

First he got a weapon made out of pipe and shaped with a head like a golf club. Then he snuck onto the yard in the afternoon. The only man out there was an old banker named Mr. Saupp. Saupp had arthritis and could lay in the sun for it with the doctor’s permission. Joe Valachi walked up to the 70-year-old man stretched on his back and beat Mr. Saupp’s face in. Then he walked across the yard to the A W’s office.

“You know that guy Joe Beck I told you about?” he said.

The AW nodded.

“I just killed him.”

It was as big a lie as Joe Valachi ever told. Mr. Saupp weighed out at 110 and Beck was at least 60 pounds heavier. One’s nose was stubby and the other’s long like Charlie Gioe’s. Saupp was killed because murderers get lockup and Joe Beck wouldn’t lie on his back and let his face get mashed.

The cops couldn’t tell who the body was. When they brought him up to the hospital, old man Saupp still wasn’t identified. Earl heard something was up and went to the emergency room. The lieutenant was examining the corpse.

“Hell,” Earl said, looking at the garbage dangling on the end of Saupp’s neck, “I know who that man is. He’s a personal friend of mine . His name’s Saupp.”

They found Saupp’s number in the index file. Then the lieutenant wanted to take Earl to isolation.

“You can’t take me,” Earl pleaded. “I didn’t do nothing. He’s a friend of mine. Whoever killed this man didn’t know him, I can tell you that. The old man wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

The doctor jumped in too. “What do you mean lock him up? He was here working all day.”

“I don’t care,” the lieutenant said. “He knew who this mess was. He knows something.”

Then the phone rang with the news about Valachi and the lieutenant split for the A W’s office.

Joe Valachi got just what he had wanted. He was locked up all by himself. The only others within shouting distance were the police. With a murder beef over his head, Joe Valachi was singing like a herd of geese. He told them that the real name of the Mafias was the Cosa Nostras. It made Page One and saved Valachi from the chair.

Valachi stayed in Atlanta isolation for a month. He came out twice a week with a five-guard escort and saw the psychiatrist in the hospital. When Earl found out, he lost his head. Mr. Saupp was Earl’s true friend and the more Earl thought about it, the sicker it made him. Earl ran over to where the plumbing crew was working and got a pipe. With the weapon hid in his pants leg, the guards paid no attention to him. Earl was just an old man who worked in the hospital.

In a second he became the mighty avenger of Mr. Saupp and rushed past Valachi’s cordon of guards. Valachi saw Earl and ran towards the office. Earl got one good swing with his pipe and took out a piece of wall right behind the snitch’s ear. It was about all Earl could do. His emphysema and the cops arrived at the same time and Earl laid down and panted. Earl Johnson was locked in the psychiatric ward for 60 days. Valachi got a ride to New Jersey. Earl still remembers him. “That dog son of a bitch deserved worse than dying, I can tell you that.”

Earl had Joe Valachi on his mind all the way through his three years and on into the next four he got for stolen bank drafts. By then he was too sick to work much and stayed on his bunk and in the hospital. He got his custody reduced from dangerous and made the rounds of the lesser institutions. After moving through four prisons, Earl caught up with Valachi at the Federal Correctional Institution, La Tuna, Texas.

It had become Valachi’s home away from home. The string of psychiatric cells in the hospital were walled off and locked with a key nobody less than a lieutenant could get. Inside, Valachi had a color TV he watched all day. For exercise, he was taken down a private stairway to a private yard by the hospital. While outside, a hack was at his side and another along the yard fence with a gun . Earl watched Valachi from a hospital window and thought about a second try.

With his body the way it was, Earl figured to use stealth. He decided to make a poison dart. Earl took a dart from the recreation yard, replaced the tip with a blood needle, and coated the point in a mixture of mercury and quicksilver. Those two together ought to be enough to kill any snitch. It took a month to steal everything necessary. Then Valachi went for his daily walk.

Earl stood on the hospital toilet and watched from his window. When the cops were looking towards Mexico, Earl threw his missile. It sailed right past Valachi’s shoulder. Valachi saw it go by and screamed 14 different brands of scream. The guards mumbled around and looked all over but never saw a thing. Earl was squatted upstairs on the shitter having the best laugh he’d had since 1924.

Joe Valachi died of a heart attack after Earl finished his time. Earl hasn’t been back inside since.

“If I go back again, I’m sure to die in there,” he explains. “Dying is something I expect, but dying in prison is the lowest dying there is .”

Earl works at staying out. “It’s hard for me out here. I ain’t used to it. I was in those places too long. Now, I’m scared to talk to people. Just having them around makes me nervous.” Earl Johnson lives on his railroad disability in a room in Palo Alto’s Cardinal Hotel. He has a dog named Sam that hangs on his footsteps like a rug. Earl keeps his “important papers” stored in a garage. They fill nine cardboard boxes. Most are clippings from magazines and copies of old indictments. His proudest possession is a birth certificate. It was forwarded to Leavenworth in 1945 by the Arkansas Board of Health. On the paper, his whole name is Earl Edison Conatesser Johnson, fathered by somebody named J.R. Johnson and delivered from one Ruth Droke. According to Arkansas, he was born in Blytheville, Mississippi County, on May 6th, 1914. But Earl isn’t sure. The sisters who raised him taught Earl May 6th, 1910. It’s still the date that sticks in his mind.

All the years since have made this old bastard’s eyes like a lizard’s. They dart across his shoulders and seem to peel back over his head. When we talked, Earl Johnson closed the ventilator over his hotel room door and checked the hallway.

“You can’t be too careful,” he explained. “There’s a lot of bad people in this world. Some dog motherfuckers .” Down by the elevator, a washerwoman’s mop slapped against a bucket and Earl Johnson’s ear turned like a key in a lock. When he looked back down the hall, all he found was the click of the doorknob, bouncing across the stairwell and off into space.

Leave a Reply