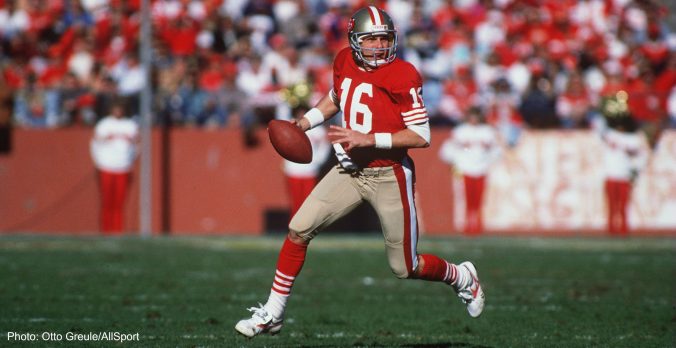

Image – 9/9/1990

This is a tribute to Joe Montana, now beginning his 12th season as quarterback of the 49ers, but first, let me put such tribute in context. I do not subscribe to the popular notion that athletes are role models for the rest of our culture. I am a hope-to-die sports fan, but to my eye, that commonly invoked sports page dogma victimizes both the athlete and our culture.

In this process, the athlete, often barely socially and intellectually prepared to roam the streets without a leash, is forced to don a cloak of moral stewardship to which he is, at best, ill suited. Hired to play games and then subjected to massive public attention if he plays them well, the athlete usually either manages the demands of role modeling with the ritual repetition of cliches or mismanages them with a narcissism attempting to pass as style. Those who fail at the masquerade often lose their game in the process. Those who prove more adept often generate a sizeable second income grinding out 60-second spots for corn flakes or footwear.

In the meantime, the culture upon which he has been foisted endlessly pursues the illusion that the athlete’s quest for physical superiority holds the spiritual forms and behavioral identities with which the rest of us can wrest human achievement and satisfaction from the void of late 20th century existence. Too often, that reliance has translated into an addiction to the 23-inch-neck approach to life – maximizing the manic application of mass, force and speed at the expense of consideration, calm and genuine communication. Shaping ourselves after the masters of third downs, zone defenses, cut fast balls and slam dunks, we have come to rely on the self-absorption, intimidation and blind momentum which so often prevail in games – at the expense of the more human aspects which go so far toward making our lives productive and livable. The dominance of athletic archetypes has often doomed us to seeking desperately to be No. 1 when in real life there are no rankings. Those kinds of role models are worse than useless. They can only trivialize our sense of ourselves.

That said, let me now explain the exceptions to my attitude. There is the rare athlete, usually one to a generation, whose unselfconscious mastery of his game and inspirational carriage in the face of both ordinary and exceptional circumstance transcend the make-believe character of sport and become symbols of how human beings can be. In retrospect, they stand out as historical landmarks, epitomizing who we were. Joe DiMaggio is the classic example. His combination of steadfast grace and unremitting achievement as center fielder for the New York Yankees during the late 1930s and again in the late’ 40s helped an entire generation come of age and find grace, steadfastness and achievement of its own. More recently; Muhammad Ali, three- time heavyweight champion during the 1960s and ’70s, provided a less classic example. His courage, originality and faith also became appropriate cultural icons. Being good at a game is not enough to qualify. Partly by an accident of time and place and partly by performance and partly by personality, the play of such athletes gives everyone insight into what is possible. In a somewhat magical synchronicity of individual performance and cultural need, the virtues of their game match the demands of the era going on around them.

Joe Montana is my nominee for the next such figure. I admit a lifetime fanatical bias for the Niners, but Montana’s career transcends my partisanship and possesses all of the necessary objective characteristics:

Montana’s game has, throughout his career, been the most visible in sport. In DiMaggio’s day, baseball was the national pastime and center fielder on the championship Yankees was its lead role. During Ali’s career, boxing’s heavyweight championship fights were the biggest sporting events in the world. Football is America’s Game now and no position in it has epitomized the era as much as quarterback of the Niners. Joe Montana calling signals for the Team of the ’80s has been the most resonant chord in sport.

Montana’s performance in that spotlight has been consistently exemplary. Legends of this stature do not possess disputed skills and Montana’s mastery of moving a football team is undisputed. His application of that mastery when everything is at stake and time is running out is often described as unparalleled. His drives at the conclusion of the 1981 NFC Championship Game against the Dallas Cowboys and the 1988 Super Bowl against the Cincinnati Bengals are already football classics. With nimble feet, eyes that seemed to see everyone and everything and an arm that was at its best when it was needed most, Montana could not be denied. Three-time Super Bowl MVP, he led the Niners to as many NFL championships as any team has ever won and they may win more before he’s done. In the numerical ratings of quarterbacks, Montana’s 112.4 in 1989 is the highest ever for a season. In the history of NFL statistics, no quarterback has ever completed more than one season rated over 100 except Montana, who has done so three times. His average rating over his career is also the highest in history. Like DiMaggio and Ali, his performance has consistently defined athletic excellence.

Most importantly, the way Montana has played his game has matched the demands of our time. Where DiMaggio provided consistency to an America traumatized by war and Depression and Ali gave imagination to an America that had become standardized, Joe Montana has brought emotional dexterity to an America deadened by excess. In an era dominated by issues of complexity and over-information, Montana has managed the most complex enterprise in sport, the Bill Walsh-designed 49ers offense, with the casual calm and instinctive invention of a kid in a pick-up game. In an era characterized by the limits of power, he has dominated the most physical of games as a relatively undersized and unimpressive physical specimen – limited and seemingly vulnerable, with little in the way of visible ego, always parrying the brutal with perception and smarts. For an America where everyone seems to live under pressure, he also offers maximum poise and implicit perspective. Hustling the Niners down the field with only double digits on the clock, he is behind his face-mask smiling. It is, his demeanor reminds us, a game that has to be played in order to be won. In an America clogged with endless hype, he has been a refreshing option, a genuine article.

That’s a role model to which even I am prepared to subscribe. In this case, that he’s an athlete only adds to its specialness.

Leave a Reply